SIU Annual Report 2018

Contents:

- Director’s Message

- Making Connections to Enhance Oversight

- Connecting with the Oversight Community

- Connecting with the Public

- Connecting with Law Enforcement

- Investing in Education

- Communications

- Outreach

- Affected Persons Program

- Training

- Statistically Speaking

- Cases at a Glance

- Charge: 17-OSA-370

- Charge: 18-OFI-095

- Closure Memo: 18-PCI-092

- Non-Charge: 18-OFI-098

- Non-Charge: 18-PCD-322

- Non-Charge: 18-PVI-140

- Non-Charge: 18-OFD-060

- Case Breakdown Chart

- 2018-2019 Financials

- SIU Organization Chart

Director’s Message

I am pleased to present the SIU’s 2018 Annual Report. In the pages that follow, you will find highlighted the issues that impacted the SIU over the year, as well as a detailed breakdown of the Unit’s caseload and financial expenditures. I hope and trust that you will find it both interesting and informative. To those seeking additional information, I encourage you to visit the SIU’s website at www.siu.on.ca.

I am pleased to present the SIU’s 2018 Annual Report. In the pages that follow, you will find highlighted the issues that impacted the SIU over the year, as well as a detailed breakdown of the Unit’s caseload and financial expenditures. I hope and trust that you will find it both interesting and informative. To those seeking additional information, I encourage you to visit the SIU’s website at www.siu.on.ca.First and most importantly, a message to my colleagues at the SIU:

“It has been a great pleasure and honour working with all of you to ensure that civilian oversight in Ontario was an example of excellence and a shining light to all other jurisdictions who strive to have a system governed by the rule of law. You deserve to be very proud of your contributions to the Special Investigations Unit, and I urge you to keep up the important work. It has been a memorable tenure with many challenges that we faced together as a Unit, and I thank you for all your diligent and hard work these past years. I have been privileged to work alongside such an impressive, committed, and hardworking team of professionals as I have come to know you all to be. The service this Unit provides to the people of Ontario is extremely important to the maintenance of confidence in the administration of justice in this province. I hope you appreciate and understand what the rest of the oversight world has recognized for a long time: you are the best.”

While the Unit has grown to become a well-respected institution known the world over for its ability to conduct independent investigations of serious injuries, sexual assault complaints and deaths in cases involving the police, the last five years has seen a desire to make the Unit even stronger. In April of 2016, the Ontario government appointed the Honourable Michael H. Tulloch to examine ways to the make the province’s system of police accountability more transparent, accountable and effective. Following the release of the findings one year later, the Ontario government committed to releasing SIU Director’s Reports to the public, a document which up until then the SIU could only share with the Attorney General. As well, new legislation for the SIU was set to take effect June 30, 2018. In addition to the Unit getting its own governing legislation after operating under the Police Services Act for more than 25 years, the definition of serious injury would be codified, the SIU would be required to investigate instances where a police officer discharged a firearm at a person (whether or not the person died or was seriously injured), and there would be potentially serious implications for officers who did not cooperate with the SIU. However, upon the new government being sworn in one day before the legislation was to take effect, the legislation was immediately revoked to allow the government to do further reviews. At the time of writing of this Message, those reviews were ongoing. I can only hope that whatever legislation is put forward will not hinder the SIU’s ability to function in a timely, impartial, thorough and effective fashion. Otherwise, the result will be inevitable delays, litigation and public suspicion of the police.

The importance of oversight is being embraced elsewhere across the country. While the SIU was the only oversight body of its kind across the country for almost two decades, similar bodies were established in British Columbia, Alberta and Nova Scotia shortly before I began my tenure at the SIU. Manitoba and Quebec established agencies in their jurisdictions shortly after I began, and now, Newfoundland and Labrador are in the final stages of creating an oversight body in their province. There is strength in numbers. The bodies across Canada continually work together to assist in investigations, collaborate to establish best practices and recently developed a committee allowing our communications staff the opportunity to formally correspond as a group on a regular basis.

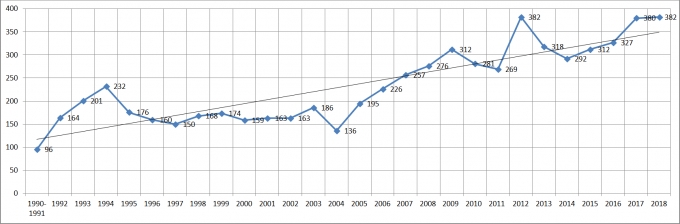

2018 was a demanding year for staff at the SIU. In addition to opening investigations into 382 cases which equalled 2012 for the highest caseload since the Unit’s inception, staff spent the first half of the year preparing for the implementation of the legislation that ultimately did not get enacted. In addition, in December the SIU took over the posting of Director’s Reports to its own website. In the long term, this will ensure the timelier reporting of our investigative findings to the affected parties and the public. And, we made efforts to be more transparent. This year, the SIU issued 518 news releases, which was an increase of 86% compared to the previous year. We also implemented a chart on our website allowing the public to track the progress of all cases from beginning to end.

At the time of publication of this Annual Report, I will no longer be the SIU’s Director. My five-year appointment commenced October 16, 2013 and expired October 15, 2018, but I was appointed for a further 51/2 months with a new term set to expire March 31, 2019. By the end of my term, I will have had the honor of serving the public as the SIU’s director for almost 5.5 years. I encourage my successor to utilize the hard work and skill of the dedicated SIU staff to continue to ensure that the important work of civilian oversight of police functions at the exceptional level it has in the past. This will serve to maintain and strengthen the confidence of the public in the essential work the Special Investigations Unit does, and ultimately ensure their continued belief in the SIU’s foremost motto: “One law for all”.

Over and out.

Sincerely,

Tony Loparco

Director, Special Investigations Unit

Making Connections to Enhance Oversight

Connecting with the Oversight Community

Canadian Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement

The 2018 Canadian Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement (CACOLE) conference was held in Winnipeg, Manitoba from May 28-30, 2018. This annual conference brings together approximately 130 delegates from police oversight agencies, community groups, law enforcement and academia from across Canada, the United States and internationally. The conference – titled Civilian Oversight - The Road Forward – included the following topics:- Civilian Oversight and Corruption Investigations in Canada; • Bias-Free Policing—Self-awareness, Unconscious Bias and the Challenge of Objectivity;

- Notes and Use of Force—Lawful Access to Officer Notes, Reports and Statements;

- Police Officer’s Duty of Loyalty and its Legal and Ethical Boundaries;

- From Complaint to Mediation/Resolution: Engaging the Unlikely Resolver;

- The Role of Governance in Effective Civilian Oversight of Policing;

- The International Perspective on Oversight; and

- People in Crisis and Policing—the Experience in Canada from East to West.

SIU Director Tony Loparco and Executive Officer William Curtis attended the conference and served as panellists on two additional topics. Director Loparco participated on the panel for the Use of Force Experts session, which looked at the role of these individuals in investigations, the law surrounding the use of their expert opinion, the pros and cons of such evidence, and the impact on investigations. Mr. Curtis was a panellist for Professionalization in Oversight, a session that discussed the potential development of curriculum and partnerships for oversight training with educational institutions.

The 2019 CACOLE conference will be held May 27-30, 2019, in Toronto, Ontario.

Videoconference with Argentina

On March 27, 2018, Director Loparco, Deputy Director Joseph Martino and Executive Officer William Curtis took part in a video conference with high-ranking Argentine government officials and Canadian diplomatic staff, including Robert Fry, the Canadian Ambassador to Argentina.The SIU spoke about its mandate, the legislation, the makeup of the SIU, and the manner in which SIU investigations unfold from beginning to end. The SIU touched on the types of cases investigated and caseload statistics, including cases that result in criminal charges. Following the video conference, Ambassador Fry wrote to the SIU:

“I wanted to thank you and your team for taking the time to share your expertise and to present the impressive work of the Special Investigations Unit to our Argentine colleagues. The discussions we had will provide material for reflection for [government officials], as they address these issues in this country.

“Exchanges of experiences such as this contribute to the ever-growing and dynamic bilateral relationship between Argentina and Canada. Thank you again for contributing to this effort.”

Visit to Baltimore Police Department

On April 27, 2018, SIU lead investigators Kazi Anwar and Dean Seymour attended the Frances Glessner-Lee Homicide Investigation Seminar in Baltimore, Maryland. While at the seminar, Mr. Anwar and Mr. Seymour were invited to the Baltimore Police Department to learn about the Special Incident Response Team (SIRT), a team within the police department that investigates:- Any use of deadly force or incident involving the death of a person while in police custody;

- Any firearm discharge by a member, including unintentional discharges;

- Any use of force resulting in great or substantial bodily injury, including injury resulting in hospital admission, loss of consciousness, or a broken bone;

- A strike to the head, neck, sternum, spine, or kidneys with an impact weapon;

- Application of greater than three CEW cycles to an individual during a single encounter; and

- Any incident involving significant misconduct by an officer in the use of force.

While the mandates between SIRT and the SIU are similar in many ways, one difference is that SIRT is not independent of the police and it does not have the jurisdiction to investigate sexual assault allegations. SIRT receives approximately 66 cases a year and has seven full-time police officers conducting the investigations.

Connecting with the Public

Director’s Resource Committee

In 2002, the SIU established the Director’s Resource Committee (DRC) in order to give voice to Ontario’s communities about the work of the SIU. Through the DRC, the SIU Director gains input and feedback on various policy matters within the SIU and is apprised of trends and issues as perceived by community members. This year, Director Loparco met with the DRC in February and November. He provided updates on the work of the SIU throughout the year, and the committee discussed upcoming changes to legislation and the potential impacts they might have on communities. The committee’s insight and advice continues to be invaluable in helping to address community concerns and in assisting the SIU improve relations with the public. It was with great sadness that the Unit learned of the passing of Bromley Armstrong this year, a long-term member of the DRC. He died on August 17, 2018. Mr. Armstrong’s unrelenting advocacy for racial and social justice, both in his personal capacity and as a founding member of the Urban Alliance on Race Relations and the National Council of Jamaicans, was pivotal in the very formation of the SIU in 1990. As a member of the DRC, his wise advice and strength of character contributed, in no small measure, to the progressive development of the SIU in times of change.

The SIU of today is a model at the forefront of civilian oversight of police both at home and abroad. The Unit regularly receives delegations from across Canada and around the world looking to learn from our experience. In fact, some of these jurisdictions have incorporated aspects of the SIU into their own systems. This is part of the important legacy Mr. Armstrong leaves behind, which we hereby recognize and strive to honour in the daily discharge of our duties.

Asian and South Asian Heritage Month Program

On May 24, 2018, the Law Society of Ontario, the Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers and the South Asian Bar Association of Toronto held their annual event commemorating Asian and South Asian Heritage Month. This year’s event explored how communities of different backgrounds can come together and build connections. Bill Lightfoot and Jodi McLaughlin, SIU legal counsel, participated in the event. The opening remarks were delivered by the Honourable Justice Maryka Omatsu. Justice Omatsu is notable for her involvement in the redress discussions between Japanese Canadians and the Government of Canada, which eventually resulted in an apology to, and compensation for, the relocation and internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War. Urban Alliance on Race Relations

On March 21, 2018, Executive Officer William Curtis and Deputy Director Joseph Martino attended a public forum at Toronto City Hall organized by the Urban Alliance on Race Relations and Policing in recognition of the United Nations’ International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The event consisted of a panel discussion – hosted by the Toronto York Labour Council and National Council of Canadian Muslims – around issues of access to justice and the systemic barriers to justice confronted by racialized and Indigenous communities.National Symposium on Mental Disorder

On February 23, 2018, SIU articling student Michael Macrae attended the 3rd National Symposium on Mental Disorder: Criminal Justice and Community Solutions. The symposium examined mental health issues that might contribute to criminal and/or anti-social actions, and how those factors may be reduced in severity or eliminated by dealing with the mental health aspects of socially and or legally deviant behaviours.Some of the points covered at the conference included:

- Police and the justice system are increasingly aware that a standard approach in which police arrest and charge people whose criminal behaviours are primarily a reflection of their mental health issues is not the best solution for anyone;

- Those with mental health issues suffer as criminals and prisoners, society suffers because of the expense of incarcerating these people (often repeatedly), the justice system suffers because it must continually deal with people in mental health crises, and the effectiveness of policing declines because police resources are frequently required to deal with people in mental health crises. The solution, as has been increasingly recognized in Canada and the United States, is to treat responses to those in mental health crises as not merely having legal/policing issues, but also as having mental health issues; and

- Such a shift in attitudes is important in Canada, because even as the crime rate in Ontario has decreased, police are increasingly likely to be called upon to deal with people in mental health crises.

Connecting with Law Enforcement

National Indigenous Policing Forum

On May 2 and 3, 2018, the Pacific Business and Law Institute hosted the National Indigenous Policing Forum in Ottawa, Ontario. Investigative manager Oliver Gordon, lead investigators Carm Anthony Piro and Pasha McKellop and Rita Koehl, SIU legal counsel, attended this event. Other attendees included elders and members of various Indigenous communities across Canada, as well as members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and other police services from across the country. The forum dealt primarily with the over-representation of Indigenous peoples in the Canadian prison population and stressed the importance of diverting resources out of the justice system, and instead directing those resources to education, counselling and intervention in a culturally based manner.

The forum addressed what powers non-Indigenous policing services had to enforce the laws in Indigenous communities, and discussed having Indigenous communities take control of their own governance and policing by passing their own by-laws and forming their own police services around traditional values.

OPP Emergency Preparedness Exercise

On May 9 and 10, 2018, at the invitation of the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), Executive Officer William Curtis and Deputy Director Joseph Martino travelled to Portland, Ontario to participate in an emergency preparedness exercise organized by the OPP. The exercise involved a simulated terrorist attack in a school giving rise to the deaths of multiple civilians, OPP officers and assailants. The SIU had the opportunity to witness firsthand how the provincial police agency might respond to a national security event of this nature, from a tactical and strategic perspective. It also provided the SIU with an opportunity to assess its own decision-making process should such an unfortunate set of circumstances come to pass in the province, including the ways in which it might work with police services to coordinate their parallel investigations. SIU Presentation to Special Constables

On September 10, 2018, the SIU played host to representatives from a number of non-police organizations that employ special constables. The gathering was initially intended to give guidance to these organizations regarding the work of the SIU under The Ontario Special Investigations Unit Act, 2018. That Act, which was scheduled to come into effect on June 30, 2018, would have brought special constables within the mandate of the SIU. Although proclamation of the Act was revoked by the Ontario government on June 29, 2018, the meeting was held as planned as there remains some prospect of special constables falling within the SIU’s investigative auspices in the event the government reintroduces legislation in this area. Some of those in attendance expressed the view that they would welcome SIU oversight.Investing in Education

Take Our Kids to Work Day

On November 14, 2018, the SIU participated in Take Our Kids to Work Day. This annual, national event allows grade 9 students, sponsored by SIU staff members, to step into their future for a day and explore the working world. In 2018, three students took part in the full day program in which they had a chance to participate in a mock SIU investigation from start to finish. During the first half of the day, the students took on roles as forensic investigators by assessing, documenting and collecting evidence at a mock scene. After “collecting” evidence, the students spent time in the forensic lab to learn about and apply forensic tests on the evidence. In the afternoon, the students transitioned into the field investigator role to conduct civilian interviews and to make the connections between the physical evidence and the witness statements. The day concluded with the students presenting their findings to the director and learning about what the director must consider before making his final decision.

The day proved to be a great success enabling the students to learn more about police oversight in Ontario, as well as inspiring them on the potential career opportunities that exist within the justice field.

Student Program

During the fall and winter months, the SIU engages in various cooperative student placements to give youth a chance to work in their field of study. The SIU connects with various colleges and universities to accommodate these placements during the year. In addition, the SIU has summer student work placements between April and August. Although the types of assignments given to students vary from year to year, some examples of experience gained at the SIU include:- Data collection;

- Legal research and memos;

- Assistance with the SIU case management system;

- Attending court and observing proceedings;

- Attending training and outreach sessions;

- Learning about P.E.A.C.E. investigative interviewing;

- Learning about investigative processes and forensic investigations;

- Participating in an investigation exercise (mock interviews, follow-up reports and the Director’s Report);

- Various administrative functions; and

- Observing investigations.

The SIU is proud of its student program and continues to be impressed with the caliber of students who have come through the program. While the students have learned much from the SIU, the SIU has also enjoyed the fresh perspectives offered by the students.

Profile: Alex Li, Summer Student

Being a student at the University of Toronto completing a double major in Criminology & Socio-Legal Studies and Political Science with a minor in Sociology, I had always hoped to study crime in a real-world setting. The SIU enabled me to gain field experience and I was allowed a firsthand look into how criminal investigations are conducted. My summer at the SIU was truly a remarkable and eye-opening experience. It was both an honour and a privilege to have worked within the agency and alongside all of the incredible staff.While shadowing criminal investigators, I attended scenes, canvased the area for surveillance footage and attended a post-mortem examination. In addition, I assisted with various call-outs to hospitals and a correctional facility. I was able to engage in ongoing investigations and analyze various investigative materials for active cases. The exposure to criminal cases and the SIU's work environment greatly contributed to my learning and further developed my passion for criminal justice.

I was also provided many research opportunities, including internal research on the prevalence and effects of vicarious trauma within employees working at the agency; I participated in Director's briefings, investigator training seminars and investigators' meetings, which were essential to understanding the workings of the SIU; I completed various tasks for legal counsel, management, administration, media relations, outreach and reception. Working at the SIU allowed me to gain new perspectives and encouraged me to always create more impact from the work that I do. I am grateful for such a memorable work term and I aspire to pursue a future career in the criminal justice system.

Communications

Communication with the Media

Communication with the media is important in ensuring that the SIU remains responsive, transparent and accountable to the public it serves. Because the SIU takes on cases at all hours of the day and night across the province, SIU Communications has made it a priority to respond to media 24 hours a day, seven days a week.From January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018, SIU Communications responded to almost 850 inquiries from media via phone, email, text, Twitter and in-person. The nature of the questions varied, with media looking for the following types of information:

- Updates on SIU cases;

- Statistics; and

- Backgrounder information to get a better understanding of SIU policies and procedures.

While the vast majority of calls were from media across Ontario, we also responded to other media reaching out to us from across the country, as well as international media. An investigation that garnered a great deal of media attention was the tragic Danforth shooting that occurred on July 22, 2018. In the days following the shooting, the SIU received and responded to approximately 100 inquiries. In addition to the case attracting interest from across the province and nationally, SIU Communications dealt with calls from US outlets including CNN, ABC News, the New York Times, Fox News, NBC, the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, as well as the Daily Mail and the Guardian in the United Kingdom.

In 2017, with almost the same caseload as in 2018, the SIU responded to approximately 960 media calls. While it is difficult to determine why there were fewer calls this year, it may be attributed to the SIU’s efforts to proactively release more information at the beginning and conclusion of investigations via the Status of SIU Cases chart, news releases and the publication of fulsome Director’s Reports.

Status of SIU Cases

The SIU is mandated with investigating incidents involving police that have resulted in serious injury, death, or an allegation of sexual assault. Due to the complexity and/or circumstances of any particular case, these investigations can require a significant amount of time to complete. Factors which may delay the completion of an investigation may be impacted by the length of time required to conduct interviews and/or gather and analyze evidence, with interviews of witness and subject officers being possibly delayed to accommodate the schedules of the interviewees, as well as the availability of counsel. Additionally, significant delay is often occasioned when the SIU has to await the completion of expert reports from outside organizations with respect to the forensic analysis of evidence or the completion of a post-mortem examination. While the SIU recognizes it is important to resolve cases in a timely manner, the thoroughness of the investigation must take precedence over the length of time it takes to finish an investigation. On July 1, 2018, in an effort to keep the public up-to-date on the progress of SIU investigations, the Unit began to proactively provide updates on each investigation via the Unit’s website at https://www.siu.on.ca/en/case_status.php .

Beginning with cases from 2017, both open and closed cases are listed. Each case includes the case number, case type, involved police service, when the SIU was notified and the status of the investigation. The ability to filter the information in several different ways is also available.

News Releases

In 2018, the SIU issued 518 news releases; in comparison, 279 news releases were issued in 2017. This was an increase of 86% over one year. Here is the breakdown:119 … News releases were issued in the early stages of an investigation

The SIU has committed to issuing news releases at the beginning of an investigation in cases where a death has occurred, a firearm has caused serious injury, major vehicle collisions and other cases that have garnered high public interest.

244 … News releases were issued in cases where the evidence did not satisfy the Director that there were reasonable grounds to lay charges

At the conclusion of an SIU investigation, if the evidence does not satisfy the Director that there are reasonable grounds to lay criminal charges, a Director’s Report is produced and posted to the SIU’s website (between spring of 2017 and December of 2018, the reports were posted to the Government of Ontario website). Each time a report is published, the SIU notifies the public of the report by issuing a news release.

136 … News releases were issued for cases terminated by memo.

In order to promote transparency, any cases that are terminated because the mandate of the SIU is not engaged, including instances in which it is determined that no serious injury was sustained, or that no complaint of misconduct is alleged, the SIU issues a news release. This practice was initiated in the summer of 2017.

15 … News releases were issued in cases where charges were laid.

In 2018, charges were laid in 15 cases, and a news release was issued each time.

4 … News releases were issued in instances not case-related (e.g. annual report, library series, etc.)

In cases involving allegations of sexual assault, the SIU, as a matter of course, will not release details to the public which could potentially identify the individual alleging a sexual assault occurred or the officer who is the subject of the allegation. While information such as time, date, location and other details of the incident could inadvertently single out a particular party, those details are not released publicly, although a limited amount of information is released if the Director has caused a charge to be laid; once the matter is placed before the court, no further information is released to the media by the SIU. The release of information related to investigations of sexual assault allegations is associated with a risk of further deterring what is already an under-reported crime and undermining the heightened privacy interests of the involved parties, most emphatically, the complainants. The SIU hopes that by not releasing identifying information in these cases, potential complainants will be encouraged to come forward. Similar to all cases, once a sexual assault investigation is underway, it is denoted on the Status of SIU Cases chart.

Police Oversight Communications Advisors Network (POCAN)

There are five other agencies similar to the SIU across the country, including the Independent Investigations Office of BC (British Columbia), the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (Alberta), the Independent Investigation Unit (Manitoba), Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes (Québec) and the Serious Incident Response Team (Nova Scotia). When someone is seriously injured or dies during an interaction with police or other law enforcement personnel, our agencies are mandated to investigate these incidents. While the mandates of these agencies differ to varying degrees, there is a great deal of common ground that the organizations share. In the Spring of 2018, the six agencies formed the Police Oversight Communications Advisors Network (POCAN) to allow communications staff from the oversight agencies the opportunity to formally correspond regularly as a group. This group affords members the opportunity to compare and contrast policies and practices, seek and offer advice and discuss issues that may be of national interest and that may require a coordinated response. POCAN also seeks to enhance the public’s understanding of our mandates and the work that these agencies do, in order to increase public confidence in both the police services and the civilian oversight agencies.

POCAN meets quarterly and corresponds outside of these meetings on an as-needed basis.

Outreach

Engagement with Ontario’s diverse communities remains central to the SIU’s outreach function, the goal of which is to promote intentional and meaningful interactions between the SIU and its community stakeholders in order to enhance transparency, encourage mutual awareness and build trust. Through outreach efforts, the SIU continues to raise awareness of the SIU’s operations, develops and strengthens community relations, and builds confidence in the work of the SIU in Ontario. In 2018, the SIU engaged in 126 presentations and meetings throughout the province to the following groups:

At the end of 2017, the SIU partnered with the Toronto Public Library to provide presentations on three themes as they pertained to the SIU. In 2018, the SIU delivered 23 presentations at 17 branches across the city.

The program received an overwhelming response, resulting in increased public interest in how the Unit operates and its role in police accountability in the province. Based on this reception, at the end of 2018, the SIU was in the process of renewing this program with the Toronto Public Library as well as extending an invitation to other municipalities in the central Ontario area. Heading into the spring of 2019, the library program was set to expand into London and Hamilton.

| Police | 18 |

| Nations | 8 |

| Community | 39 |

| Academia (High school, College, University) | 61 |

| Totals | 126 |

|---|

Partnering with Libraries

At the end of 2017, the SIU partnered with the Toronto Public Library to provide presentations on three themes as they pertained to the SIU. In 2018, the SIU delivered 23 presentations at 17 branches across the city. The program received an overwhelming response, resulting in increased public interest in how the Unit operates and its role in police accountability in the province. Based on this reception, at the end of 2018, the SIU was in the process of renewing this program with the Toronto Public Library as well as extending an invitation to other municipalities in the central Ontario area. Heading into the spring of 2019, the library program was set to expand into London and Hamilton.

Affected Persons Program

The Affected Persons Program (APP) is a vital component of the SIU, providing support services to those negatively impacted by incidents investigated by the Unit. The Program aims to respond to the psychosocial and practical needs of complainants, their family members and witnesses by offering immediate crisis support, information, guidance, advocacy and referrals to community agencies. Support services are also available to complainants and witnesses through the Affected Persons Court Support Program if an investigation results in criminal charges. Program staff are available to respond to the needs of affected persons 24 hours a day, seven days a week.The establishment and maintenance of collaborative relationships with government and community partner agencies across the province is essential to the success of the program. These efforts continued throughout 2018, in coordination with the Ontario Network of Victim Service Providers, Victim Service Units, Victim Witness Assistance Programs and the Office of the Chief Coroner.

In 2018, the Affected Persons Program provided support in 101 cases.

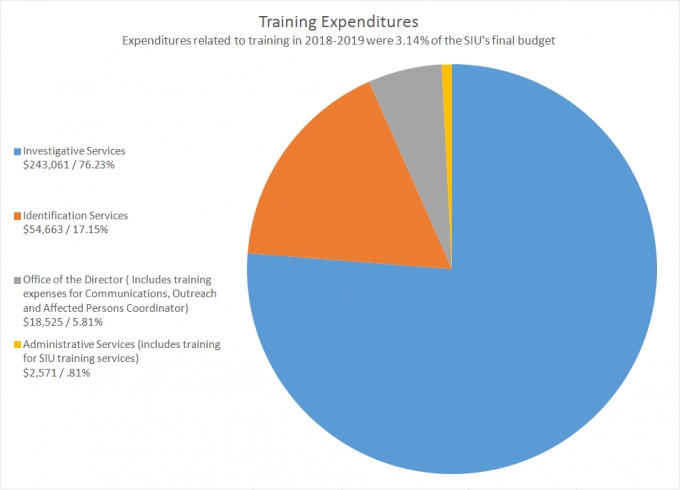

Training

During the 2018 calendar year, the Unit welcomed five new investigators and one forensic investigator, including three civilians and three former police officers, to the team. In keeping with past practices, the investigators attended a five week in-class orientation before participating in a six-month coaching program.Over the course of the year, SIU staff participated in learning and development initiatives totaling more than 5,300 hours, with over 85% of this training devoted to the investigative staff. The Unit continued the practice of having investigators attend both the Ontario Police College and the Canadian Police College, as these institutions continue to be our best resource with respect to accredited criminal investigation training. The Unit strives to ensure that investigative staff attend, at the minimum, the following course offerings:

- Criminal Investigation Training and Education;

- Sexual Assault Investigation;

- P.E.A.C.E. Model of Investigative Interviewing;

- Investigative Interviewing Techniques; and

- Homicide Investigation course (full-time investigators).

The Unit continues to facilitate in-house seminars for investigators which include Peer Case Reviews, technical and technologically-based presentations (firearms familiarization, GPS / AVL software overviews, etc.) as well as specifically targeted health and safety initiatives (Introduction to Mental Health First Aid, Naloxone training, etc.).

Investigative staff also attended external topical seminars which directly relate to the Unit’s mandate, including:

- The Frances Glessner-Lee Homicide Seminar (Baltimore, MD);

- Programs offered by the Canadian Association of Technical Accident Investigators and Reconstructionists;

- Programs offered by the Inaugural Ontario Forensic Investigators Association;

- The National Indigenous Policing Forum;

- The 2018 Sexual Assault Investigator's Association of Ontario Conference; and

- The Toronto Police Service 27th Forensic Training Conference.

Going forward, the SIU is continuing to investigate future training offerings as it prepares for the release of an updated Special Investigations Unit Act and transitions to agency status.

In an effort to build on past cultural competency initiatives, while complying with the provincial government’s goal of full Ontario Public Service attendance at Indigenous cultural competency training by 2021, the Unit facilitated the ‘Bimickaway’ program. ‘Bimickaway’, which is an Anishinabemowin word meaning ‘to leave footprints’, uses an Indigenized and Indigenous methodological approach to its delivery. It is ideally only delivered in settings of 25 people to ensure meaningful group discussions and activities. An Indigenous Elder is invited to attend to add their meaningful life experiences to the curriculum.

This training incorporates an interactive approach in which staff are encouraged to reflect on what they have learned about the Indigenous peoples.

This exercise is both experiential and participatory, and is designed to take participants through the history of assimilative government laws and policies in order that the participants:

- Experience a visceral reaction to the taking of land and the imposition of policies and laws, such as the Indian Residential School System;

- Learn about the realities of access to justice for Indigenous peoples living in Northern Ontario; and

- Learn about anti-Indigenous racism including topics such as: commodification of Indigenous bodies, cultural appropriation and the role of the media.

The curriculum and activities of this program are geared towards the day to day application of the previous modules to the work of the Unit.

Statistically Speaking

Cases Opened by the SIU

During the 2018 calendar year, 382 cases were opened by the Unit, a slight increase from the 380 cases that were opened in the 2017 calendar year.Types of Occurrences by Percentage

Number of Investigations Launched per Month

Total Occurrences Trend

| Occurrences | '09 | '10 | '11 | '12 | '13 | '14 | '15 | '16 | '17 | '18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firearm Deaths | 7 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Firearm Injuries | 9 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| Custody Deaths | 19 | 21 | 21 | 32 | 17 | 19 | 27 | 25 | 19 | 36 |

| Custody Injuries | 184 | 171 | 142 | 229 | 194 | 169 | 188 | 197 | 229 | 198 |

| Other | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 19 |

| Vehicle Deaths | 7 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 6 |

| Vehicle Injuries | 54 | 27 | 27 | 44 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 42 | 46 |

| Sexual Assault Allegations | 29 | 37 | 53 | 49 | 39 | 43 | 40 | 43 | 68 | 58 |

| Totals | 312 | 281 | 269 | 382 | 318 | 292 | 312 | 327 | 380 | 382 |

* Totals include cases reported but not mandated (73 cases in 90-91 and 69 cases in 1992).

How the SIU is Notified

The majority of the time, the involved police service notifies the Special Investigations Unit. All police services in Ontario are legally obligated to immediately notify the SIU of incidents that involve death or serious injury – including allegations of sexual assault. However, calls from police are not the only way the SIU can be notified. In fact, anyone can contact the Special Investigations Unit about an incident that falls within its mandate. Of the 382 investigations launched by the Unit in 2018, here is how the SIU was notified:

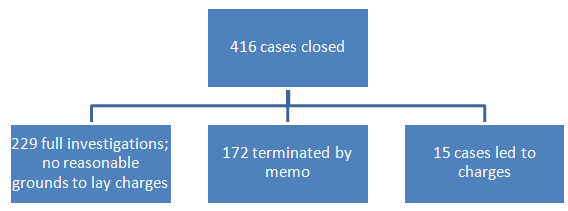

Cases Closed by the SIU

From January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018, the SIU closed 416 cases. The number of closed cases includes occurrences from the previous year that were closed in 2018 and does not include cases that remained open at the end of 2018. The average number of days to close all cases was 129.39 days. The SIU incorporates a practice of “stop/restart dates” to calculate the length of its cases from start to finish. There are times during the course of certain cases where the SIU investigation is on hold pending some action of a third party over which the SIU has no control; this sometimes happens, for example, when an outside expert has been retained to provide an opinion regarding physical evidence and the investigation cannot proceed further until the expert’s opinion has been received. In that case, a “stop date” is indicated when the expert is retained and a “restart date” is indicated when the opinion is received. The interval of time between the stop and restart dates is excluded from the overall length of the case. By subtracting periods of time during which an investigation is on hold pending some action by a third party, which is outside of the control of the SIU, the data more accurately reflects the time spent by the SIU investigators on active investigations.

Cases Closed with No Reasonable Grounds to Lay Charges

In the majority of cases investigated by the SIU, the Director concluded that the evidence did not establish reasonable grounds to believe that there had been criminal wrongdoing on the part of the officers, and hence, no charges were laid. Based on an analysis of the evidence in each of these investigations, a finding was made that either the officers did not act outside of the parameters of the criminal law, or that there was insufficient evidence to make that determination. In 2018, 229 investigations ended in this manner.Cases Closed by Memo

Of the 416 cases closed in 2018, 172 were closed by memo, accounting for 41% of the total number of cases. In some SIU cases, information is gathered at an early stage of the investigation which establishes that the incident, at first believed to fall within the SIU’s jurisdiction, is in fact not one that the Unit can investigate. It may be that the injury in question, upon closer scrutiny, is not in fact a “serious injury” according to the definition of serious injury that the SIU has established. In other cases, although the incident falls within the SIU’s jurisdiction, it becomes clear that there is patently nothing to investigate. Examples of such incidents include investigations in which it becomes evident early on that the injury was not directly or indirectly caused by the actions of a police officer. In these instances, the SIU Director exercises his/her discretion and “terminates” all further SIU involvement, filing a memo to that effect with the Deputy Attorney General. When this occurs, the Director does not render a decision as to whether a criminal charge is warranted in the case or not. These matters may, on occasion, be referred to other law enforcement agencies for investigation.

Charge Cases

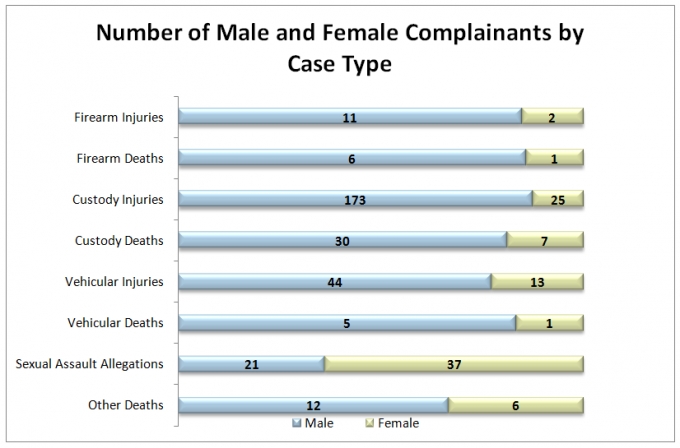

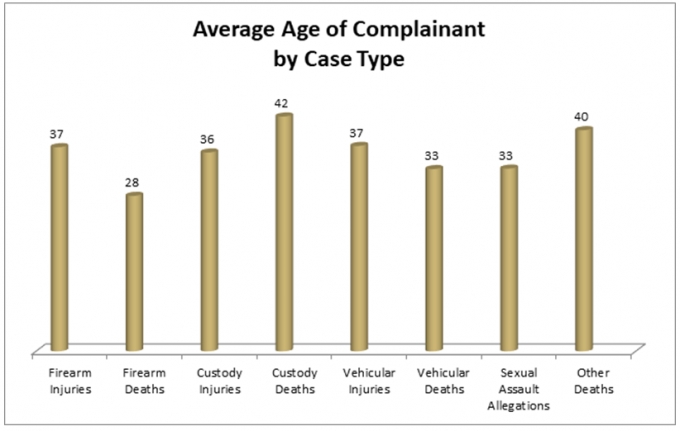

Criminal charges were laid by the SIU Director in 15 cases, against a total of 17 officers, accounting for 3.6% of the 416 cases that were closed in 2018. These charge cases included investigations that were launched in prior years, but for which charges were laid in 2018.Information About Complainants

Complainants are individuals who are directly involved in an occurrence investigated by the SIU in that, as a result of interactions with police, they have died or were seriously injured, or they are alleging that they had been sexually assaulted. There may be more than one Complainant per SIU case.

Investigative Response

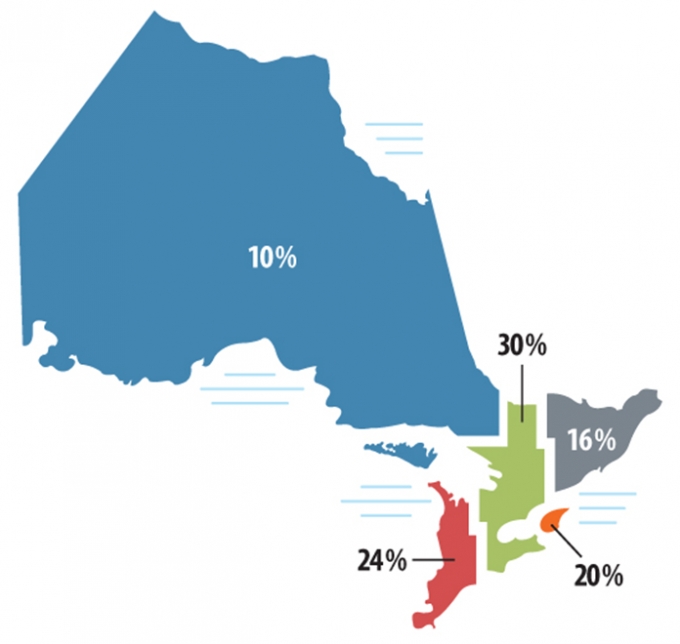

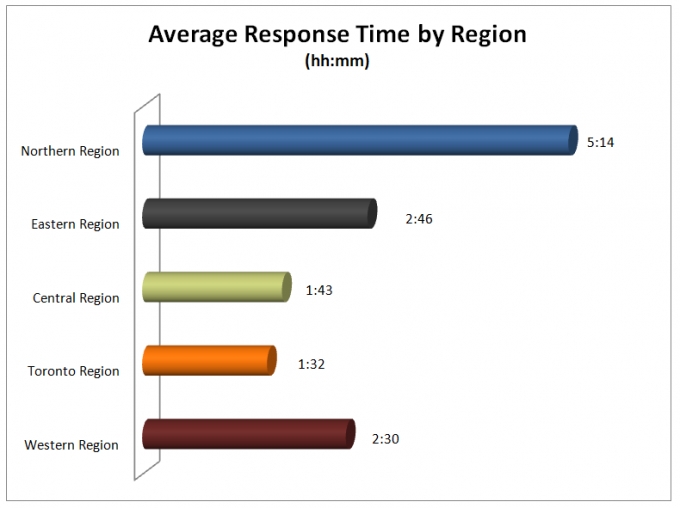

To assist in understanding the required investigative response in an SIU incident, the SIU tracks the time it takes for investigators to respond to an incident and the number of investigators deployed to a scene. Speed of response and the number of investigators initially dispatched to an incident are important in many cases because of the need to secure physical evidence and to meet with witnesses before they leave the scene.Investigations by Region

* The times calculated were for cases that required an immediate response; cases which required a scheduled response (meaning a response at a later time or date) were not included in this calculation.

* The times calculated were for cases that required an immediate response; cases which required a scheduled response (meaning a response at a later time or date) were not included in this calculation.

Cases at a Glance

The nature of the SIU’s mandate means that the Unit often deals with complex and traumatic situations involving police and civilians. Examining these situations, and arriving at a decision, is rarely easy. Under section 113(7) of the Police Services Act, the Director, who cannot be a former police officer, has the sole authority at the SIU to decide whether or not charges are warranted. The Director relies on many years of experience in the area of criminal law and takes into consideration all aspects of an investigation, arriving at a decision by applying established legal principles. The Director’s job is not to decide whether the police officer, who is the subject of an investigation, is innocent or guilty, but rather whether or not the evidence satisfies the Director that there are reasonable grounds to pursue criminal charges. If a charge is laid, the courts will ultimately determine guilt or innocence by deciding whether the charge has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt. The following are examples of investigations carried out by the SIU during 2018:Charge: 17-OSA-370

Incident Overview

The SIU was contacted by the Ottawa Police Service (OPS) on November 22, 2017 regarding a complaint of a sexual nature against an OPS officer. The alleged assault reportedly occurred against a woman in Ottawa on October 25, 2017.The Investigation

The SIU assigned two investigators to examine the circumstances surrounding this incident. As part of the investigation, the SIU interviewed the woman who made the allegation and one civilian witness. The subject officer declined to be interviewed and did not provide a copy of his notes to the SIU, as is the subject officer’s legal right. In addition to the interviews, the SIU reviewed evidence including Global Positioning System data and Communications and Computer-Aided Dispatch documents.

Director’s Decision

Based on the evidence and information collected in relation to this incident, SIU Director Tony Loparco concluded that there were reasonable grounds to believe a Sergeant with the Ottawa Police Service committed criminal offences. As a result, on September 24, 2018, the Sergeant was charged with the following Criminal Code offences: - One count of sexual assault, contrary to s. 271; and

- One count of breach of trust by public officer, contrary to section 122.

The case was then referred to the Justice Prosecutions Branch of the Crown Law Office—Criminal, for prosecution. As of December 31, 2018, this case remained before the courts.

Charge: 18-OFI-095

Incident Overview

On March 31, 2018, the Hamilton Police Service became involved in a break and enter investigation related to a property in Flamborough. A vehicle had also been stolen from the property. Upon tracking the stolen vehicle to an industrial area in Cambridge, the Waterloo Regional Police Service was notified and officers were dispatched to the area. One of the officers located the man and there was an interaction. The officer discharged his firearm at the man several times. The man was struck one time and transported to hospital for treatment.The Investigation

The SIU assigned seven investigators and three forensic investigators to examine the circumstances surrounding this incident. The subject officer declined to be interviewed, as is his legal right, but did provide the SIU with a will state detailing his involvement. As part of the investigation, the SIU interviewed the injured man, three civilian witnesses and 16 witness officers.In addition to reviewing evidence found at the scene, the Unit reviewed:

- Computer Aided Dispatch event details;

- GPS data from police vehicles;

- WRPS Communications Recording; and

- CFS results.

Director’s Decision

Based on the evidence and information collected in relation to this incident, SIU Director Tony Loparco concluded that there were reasonable grounds to believe that a WRPS officer committed criminal offences. As a result, on November 18, 2018, the officer was charged with the following Criminal Code offences:- One count of attempt murder, contrary to s. 239;

- One count of aggravated assault, contrary to s. 268;

- One count of discharge firearm with intent, contrary to s. 244(1); and

- One count of discharge firearm-reckless endangerment, contrary to s. 244.2(1)(b).

The case was then referred to the Justice Prosecutions Branch of the Crown Law Office—Criminal, for prosecution. As of December 31, 2018, this case remained before the courts.

Closure Memo: 18-PCI-092

Incident Overview

At approximately 10:15 p.m. on March 28, 2018, Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) officers responded to a single motor vehicle collision on Highway 401, in the area of Wellington Road in London. The driver of the vehicle – which had been reported stolen earlier that day – fled the scene. A short time later, officers with the London Police Service (LPS) received a call regarding a break and enter at a business. Upon arrival at the business, officers located and arrested a man exiting from a window. Subsequent investigation revealed that that was the same man who had earlier fled from the collision scene. The 28-year-old man was transported to hospital for treatment.The Investigation

The SIU assigned three investigators to probe the circumstances of this incident. As part of the investigation, the 28-year-old man was interviewed on two separate occasions.

Due to the involvement of the OPP and LPS in dealing with the man, the SIU requested and received the following materials and documents from both police services:

- LPS records and communications recordings;

- OPP records and communications recordings;

- OPP photographs;

- OPP interview report (from an individual who had witnessed the collision); and

- Security video footage from the business premises.

Director’s Decision

Director Loparco terminated the investigation, finding that, “The evidence clearly establishes that the man sustained his injuries in a single car accident prior to any contact with the police.”Non-Charge: 18-OFI-098

Incident Narrative

On April 1, 2018, a 911 call was received by the Greater Sudbury Police Service (GSPS) from a security officer at the Downtown Transit Terminal, in the City of Sudbury, requesting police assistance. The caller reported that a man, Complainant #1, was in the terminal and was carrying two large knives, and was walking around the terminal and trying to break into the security office.As a result, four GSPS police officers were dispatched, arriving at the terminal while the 911 caller was still on the line. The subject officer (SO) was armed with a C-8 rifle and witness officer (WO) #2, WO #1, and WO #3 were all armed with their service pistols and Conducted Energy Weapons (CEWs). The police officers entered the bus terminal via the west side centre door and stood side by side; they saw Complainant #1 in the south portion of the terminal pacing in and around the passenger area grasping two knives, one in each hand. The police officers repeatedly ordered Complainant #1 to drop the knives, but he ignored those commands. The distance between the police officers and Complainant #1, at that point, was approximately 30 feet.

WO #2 drew his service pistol, WO #1 and WO #3 drew their CEWs, and the SO levelled his C-8 carbine rifle; all had their weapons pointed at Complainant #1, while yelling at Complainant #1 to drop his knives. WO #1 readied his CEW, by locking its red laser beam on Complainant #1’s chest and centre mass. Complainant #1 then suddenly raised both knives above his head, grasping them by the hilts while pointing the blades in the direction of the police officers, began to scream, and then rushed directly towards the four police officers.

Both WO #1 and WO #3 discharged their CEWs and observed the probes strike Complainant #1’s chest and abdomen area. The deployment of the CEWs, however, appeared to have no effect on Complainant #1, as he continued to rush at the police officers with his knives pointed at them.

All four of the police officers jumped back as Complainant #1 ran at them; WO #s 1-3, who were situated in the centre of the corridor, were able to back away and increase the distance between themselves and Complainant #1. The SO, who was on the west side of the terminal, backed up against the glass panel wall enclosing the entranceway into the terminal and was unable to retreat any further.

Complainant #1 ran down the centre of the corridor directly at WO #s 1-3. As he passed by the location of the SO, the SO turned his body toward Complainant #1 and discharged his rifle three times. One bullet made contact with the Complainant’s right flank as he became perpendicular to the SO, with the other two striking the external wall of the security office, which was directly across from the SO, penetrating its light metal exterior. Complainant #2, a 39-year-old man who was inside the security office, was struck in the left shin area either by a bullet fragment which penetrated the wall of the security office and was propelled forward, or by a piece of metal shrapnel propelled by a bullet strike.

Complainant #2 attended the hospital, where a “metallic foreign body” was located 14 centimetres beneath the skin’s surface on his left tibia (shinbone); no fracture or dislocation was located. The fragment was removed from his leg and the wound was cleaned and bandaged; Complainant #2 was released from hospital immediately thereafter.

Complainant #1 sustained a gunshot wound to his left flank and was admitted to hospital, where he underwent surgery to remove the bullet. The bullet traversed the flank, but fortunately missed a number of major arteries and blood vessels. The bullet splintered into many fragments which became lodged in his Acrum (lower back); these were not removed during surgery. Complainant #1’s bladder was also impacted by the bullet and required that a catheter be inserted. Complainant #1 was released from the hospital approximately three weeks later.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned four investigators and two forensic investigators to probe the circumstances of this incident. In addition to examining the scene and collecting evidence, SIU investigators interviewed the two individuals who were injured – Complainant #1 (the 24-year-old man) and Complainant #2 (the 39-year-old man) – and obtained and reviewed their medical records. Six civilian witnesses (CWs) were interviewed. Three witness officers were interviewed, and the notes from 17 other police officers were received and reviewed. The subject officer declined to be interviewed and did not provide a copy of his notes to the SIU, as is the subject officer’s legal right.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the GSPS:

- 911 call recording;

- Police Transmissions Communications Recording;

- CPIC Response Report-GSPS;

- Event Chronology;

- General Report;

- GSPS witness statement of CW #4;

- Notes of WO #s 1-3 and 17 undesignated police witnesses;

- Officer involvement list;

- CEW download data;

- Will States from undesignated GSPS officers; and

- Witness list.

The SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from other sources:

- DNA report dated June 14, 2018 from the Centre of Forensic Sciences (CFS);

- Firearms report dated May 15, 2018 from the CFS;

- Medical records of both injured individuals;

- CEW download data;

- Cell phone recording of incident by witness; and

- CCTV recording from bus terminal.

Director's Decision

After a thorough analysis of the evidence, Director Loparco came to the following conclusion:Pursuant to s. 25(1) of the Criminal Code, a police officer, if he acts on reasonable grounds, is justified in using as much force as is necessary in the execution of a lawful duty. Further, pursuant to subsection 3:

(3) Subject to subsections (4) and (5), a person is not justified for the purposes of subsection (1) in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm unless the person believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the self-preservation of the person … from death or grievous bodily harm.

As such, in order for the SO to qualify for protection from prosecution under section 25, it must be established that he was in the execution of a lawful duty, that he was acting on reasonable grounds, and that he used no more force than was necessary. Furthermore, pursuant to subsection 3, if death or grievous bodily harm is caused, it must further be established that the police officer did so believing on reasonable grounds that it was necessary in order to preserve himself or others under his protection from death or grievous bodily harm.

Turning first to the lawfulness of Complainant #1’s apprehension, it is clear from both the 911 call and the direct observations of the four police officers present, as well as upon the evidence of the two Complainants and the six civilian witnesses, that Complainant #1 was in possession of weapons that were dangerous to the public peace, contrary to s. 88 of the Criminal Code, and he was arrestable for that offence. As such, the apprehension and arrest of Complainant #1 were legally justified in the circumstances.

With respect to the other requirements pursuant to s.25(1) and (3), I am mindful of the state of the law as set out by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Nasogaluak [2010] 1 S.C.R. 206, as follows:

Police actions should not be judged against a standard of perfection. It must be remembered that the police engage in dangerous and demanding work and often have to react quickly to emergencies. Their actions should be judged in light of these exigent circumstances. As Anderson J.A. explained in R. v. Bottrell (1981), 60 C.C.C. (2d) 211 (B.C.C.A.):

In determining whether the amount of force used by the officer was necessary the jury must have regard to the circumstances as they existed at the time the force was used. They should have been directed that the appellant could not be expected to measure the force used with exactitude. [p. 218]

The court describes the test required under s.25 in the following words:

Section 25(1) essentially provides that a police officer is justified in using force to effect a lawful arrest, provided that he or she acted on reasonable and probable grounds and used only as much force as was necessary in the circumstances. That is not the end of the matter. Section 25(3) also prohibits a police officer from using a greater degree of force, i.e. that which is intended or likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm, unless he or she believes that it is necessary to protect him - or herself, or another person under his or her protection, from death or grievous bodily harm. The officer's belief must be objectively reasonable. This means that the use of force under s. 25(3) is to be judged on a subjective-objective basis (Chartier v. Greaves, [2001] O.J. No. 634 (QL) (S.C.J.), at para. 59).

While the SO did not provide a statement, there is ample evidence that the three witness officers reasonably believed that they were at risk of death or grievous bodily harm from Complainant #1 at the time that the SO discharged his firearm. Since each of the four police officers present were in possession of the same information at that time, I find that the beliefs by the three witness officers that their lives were at risk of death or grievous bodily harm would have been shared by the SO. As such, I believe that there is ample evidence that the SO, subjectively, had reasonable grounds to believe that he, or the other three police officers present, were at risk of death or grievous bodily harm from Complainant #1 at the time that he discharged his firearm.

With respect to whether or not there were objectively reasonable grounds to believe that the lives of the police officers inside the terminal were at risk of death or grievous bodily harm from Complainant #1, one need only refer to the objective bystanders who actually witnessed the actions of Complainant #1, as follows:

- A number of the witnesses, and Complainant #1 himself, confirmed that numerous demands had been made by the police officers for Complainant #1 to drop his weapons, all of which were ignored by Complainant #1;

- Complainant #2 and CW #2, who barricaded themselves inside the security office, both indicated that they feared for their safety from Complainant #1;

- CW #4, a Greater Sudbury Transit employee, indicated that Complainant #1 got very close to the three police officers with the knives poised and pointed in their direction, before the SO discharged his rifle;

- CW #5 indicated that she believed that Complainant #1 was purposely attacking the police officers and was within eight feet of the officers when he was shot;

- Etc.

Additionally, the fact that WO #1 dropped his CEW, after the ineffective deployment, stepped back, and was reaching for his firearm, and that WO #2 already had his firearm in hand and was squeezing the trigger, when the SO discharged his rifle, appears to clearly substantiate that each of these two officers also felt that their lives were at risk from Complainant #1, and that they were each willing to resort to lethal force to protect themselves from death or grievous bodily harm.

Finally, having viewed both the CCTV footage, and the footage as captured by CW #3 with his cellphone, it is clear that this was a fast-moving and fluid situation, with Complainant #1 suddenly charging at the police officers with weapons raised, while the officers first resorted to the use of the CEWs, before then jumping back and retreating to save themselves. On this evidence, I am unable to find that the SO had any other viable option at that time to save the lives of his colleagues, other than the resort to lethal force. I note, however, that as soon as Complainant #1 was hit and went to the floor, no further shots were fired.

I find, therefore, on this record, that the lethal force resorted to by the SO, which lead to the serious injury sustained by Complainant #1, and the less serious injury sustained by Complainant #2, was justified pursuant to s. 25(1) and (3) of the Criminal Code, and that the SO, in preserving the lives of his three colleagues, used no more force than was necessary to affect this lawful purpose. As such, I lack the reasonable grounds to believe that the actions exercised by the SO fell outside the limits prescribed by the criminal law and instead find there are no grounds for proceeding with criminal charges in this case.

The Director’s Decision found here has been condensed from its original version. The full analysis, along with details on the evidence collected and relevant legislation, can be found at https://www.siu.on.ca/en/directors_report_details.php?drid=251.

Non-Charge: 18-PCD-322

Incident Narrative

The Complainant, a 40-year-old man, suffered from mental illness and had suicidal ideations; in the days leading up to his death, he had asked both civilian witness (CW) #1 and CW #2 to shoot him, as he did not wish to live anymore. On November 1, 2018, the Complainant abducted CW #1 from her residence and placed her in his vehicle with the intention of taking her to his residence, apparently because he wanted her to shoot him in the woods. En route to the Complainant’s residence, he was intercepted by two OPP officers, who had been advised by the Durham Regional Police Service of the abduction and kidnapping of CW #1. The Complainant stopped his truck on Tuckers Road near the Town of Apsley. As the subject officers (SOs) approached the vehicle to arrest the Complainant, the Complainant, while still seated in the driver’s position, placed a .308 rifle under his chin and discharged it, in the presence of CW #1, who was handcuffed and seated in the front passenger seat. The Complainant’s .308 rifle was found positioned between his legs, with the barrel pointing upward. The firearm was checked and there was a spent cartridge in the chamber of the rifle. CW #1 immediately exited the passenger seat of the vehicle screaming and shouting that the Complainant had shot himself. The Complainant was pronounced dead at the scene.The pathologist who carried out the post-mortem examination on the body of the Complainant determined that cause of death was due to a “Submental (from the area under the chin) Gunshot Wound Perforating Head and Brain.”

The Investigation

The SIU assigned three investigators and three forensic investigators to probe the circumstances of this incident. The SIU interviewed two civilian witnesses and designated eight police officers as witness officers (WOs). Of those eight, two were interviewed and it was deemed not necessary to interview the remaining six based on a review of their notes. Both SOs were interviewed, but both declined to submit their notes, as is their legal right.

The truck containing the Complainant’s body, still seated in the driver’s seat, was parked near 56 Tuckers Road (a gravel road) in the Township of North Kawartha, in the County of Peterborough. The truck was on the north shoulder, roughly 310 metres west of Highway 28. The Complainant was behind the steering wheel of his black Ford truck and the engine was still idling at the time that the SIU investigators arrived at the scene. A .308 calibre bolt action rifle was located between the Complainant’s legs. The barrel of the rifle was located in the Complainant’s left hand and his right hand was between his legs and proximal to the trigger area. There was one spent cartridge case in the chamber of the rifle and three live rounds in the magazine.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the OPP:

- GPS from the police cruisers being operated by SO #1 and SO #2;

- Notes of WO #s 1-8;

- Police Transmissions Communications Recordings;

- Computer-Aided Dispatch Event Report;

- Private Firearm Acquired - CFP; and

- Provincial Call Centre (PCC) Communications Summaries (x3).

Director's Decision

Director Loparco reviewed and analysed all of the evidence obtained, and came to the following conclusion:This unfortunately is another case in which a man with mental health issues (the Complainant), was acting irrationally, which led to the police being called to deal with his conduct. However, the evidence is absolutely clear that within approximately three minutes of SO #2 parking behind the Complainant’s truck, the Complainant shot himself in the head and that SO #2 and SO #1 were in no position to do anything about it. SO #2 was the first of two officers who parked directly behind the Complainant’s truck at the scene of the tragic incident. The Complainant, who had kidnapped CW #1 and then, when pursued by SO #2, stopped on Tuckers Road. He knew that the police were behind him. At that point, he told CW #1 that he would be imprisoned for 25 years (for what he had done) and he could not go back to jail. He then reached for a rifle he had stashed behind his driver’s seat. Prior to the police being able to have any physical contact with the Complainant, he placed the gun between his legs, despite CW #1’s attempt to stop him, and he pulled the trigger. CW #1 was splattered with the Complainant’s blood and brain matter and she fell, screaming, from the front passenger seat of the car.

The police officers who had followed the Complainant to Tuckers Road were acting within the scope of their legal duties when attempting to arrest the Complainant. Moreover, their only “interaction” with the Complainant was when SO #2 yelled out that the Complainant was under arrest and that he was to get out of the car and lay on the ground. Given the circumstances, SO #2 had every right to issue this directive; nonetheless, before either police officer could say anything else or take any other action, the Complainant shot and killed himself. I find that their conduct did not in any way fall outside of the parameter of what was legally appropriate in the circumstances and cannot provide the basis for believing that any criminal offence occurred, and as a result, no criminal charges will issue.

The Director’s Decision found here has been condensed from its original version. The full analysis, along with details on the evidence collected and relevant legislation, can be found at https://www.siu.on.ca/en/directors_report_details.php?drid=242.

Non-Charge: 18-PVI-140

Incident Narrative

At approximately 1:47 a.m. on May 11, 2018, police officers from the Toronto OPP Detachment, subject officer (SO) #1, witness officer (WO) #1, WO #2, and WO #3, were conducting RIDE spot checks at Hwy 410 and Queen Street in the City of Brampton when a Chevrolet Traverse SUV motor vehicle drove through the spot check area without stopping. Although the vehicle initially slowed, when the officers approached, the Traverse sped off striking SO #1 in the shoulder/arm area. The police officers then entered two separate police vehicles and pursued the Traverse. SO #1 was driving the first police vehicle, followed by WO #2 driving the second.Both police vehicles engaged the Traverse in a vehicular pursuit, with the intention of stopping the vehicle and investigating the driver for possible impaired driving, as well as for dangerous driving and assault with a weapon, for striking and injuring SO #1. At one point, the officers lost sight of the Traverse, but later located it near the dead end of Kipling Avenue, north of Steeles Avenue West, after it had apparently been involved in a single vehicle collision. Both the driver, Complainant #1, and the passenger, Complainant #2, were removed from the motor vehicle and arrested, following which they were taken to hospital.

SO #2, the Communications Supervisor, monitored the pursuit from the Communications Centre at OPP Headquarters in Orillia and was responsible for ensuring that the pursuit was conducted appropriately and did not endanger the public. At no time did SO #2 direct the police officers involved to terminate the vehicular pursuit.

Following a Computerized Tomography (CT) scan, Complainant #1 was diagnosed with a small intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding inside the brain or skull), an L3L4 transverse process (a bony protrusion from the back of a vertebrae bone in the spine) fracture, a retrosternal hematoma (bleeding behind the sternum), and a lung contusion, and was referred to a specialist for follow up.

Complainant #2 also had a CT scan, following which he was diagnosed with a nasal bone fracture, a left humerus head (where the long bone in the arm connects to the body) fracture, and a left shoulder dislocation, for which he was also referred to a specialist for follow up.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned four investigators, three forensic investigators and one collision reconstructionist to probe the circumstances of this incident. The SIU interviewed both Complainants who had been injured – the 36-year-old male driver and the 25-year-old male passenger – and obtained and reviewed their medical records. Six witness officers were also interviewed. Two subject officers were identified and designated. The subject officer who was driving the lead pursuit vehicle during the suspect apprehension pursuit declined to be interviewed and did not provide her notes, as is her legal right. The second subject officer, the communications supervisor who was monitoring the pursuit, declined to be interviewed but did submit his notes. No civilian witnesses were identified, nor did any come forward to provide information.

The SIU reviewed CCTV video from 10 commercial premises, three city buses and four bus stops.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the OPP:

- Police Transmission Communications Recordings;

- Recordings of Telephone Calls of SO #2 on OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC phones, during the pursuit;

- Scene Video;

- Photos of Traverse, later determined to be a stolen motor vehicle;

- 11 CCTV videos provided by OPP from premises on route of pursuit;

- Aerial Photos;

- Affidavits of the OPP Technical Analyst (x4) re: downloaded data from police vehicles;

- Arrest Report (Complainant #1);

- Crown Brief Synopsis for charges against Complainant #1;

- Prepared Diagrams (x3);

- Event Details Report;

- Fail to Stop Report;

- General Report;

- GPS Gate Data Table for the police vehicles operated by SO #1 and WO #2;

- List of Involved Officers;

- Mobile Public Safety (MPS) Data Tables for the police vehicles operated by SO #1 and WO #2;

- Crash Data Retrieval (CDR) reports for Traverse and both involved police vehicles;

- Notes of WO #s 1-3 and SO #2;

- Preliminary Collision Reconstruction Report prepared by OPP officers;

- Notes of officers involved in preparation and investigation of Collision Reconstruction (x6) and deployment of drone;

- Final OPP Collision Reconstruction Report;

- OPP Scene Photos;

- OPP Unmanned Aerial Surveillance (UAS) Pre-Flight Checklist Report;

- OPP Witness Statement from undesignated witness re: stolen licence plates on Traverse;

- Quality Report (Steeles report) for UAS;

- Training Records for WO #s 1-3 and SO #1;

- Vehicle Damage Report; and

- Vehicle Exam Field Notes for the Traverse and the police vehicles operated by WO #2 and SO #1.

Director's Decision

After thoroughly reviewing and analysing the evidence, Director Loparco made the following finding:The question is whether, on these facts, there are reasonable grounds to believe that any of the officers involved in the pursuit of the Traverse, or who were monitoring the pursuit as communications supervisor, committed a criminal offence, specifically, whether or not the driving rose to the level of being dangerous and therefore in contravention of s.249 (1) of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm contrary to s.249 (3) or if the pursuit amounted to an act of criminal negligence contrary to s.219 of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm (s.221).

The decision of the Supreme Court of Canada R. v. Beatty, [2008] 1 S.C.R. 49, defines s.249 as requiring that the driving be dangerous to the public, “having regard to all of the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that, at the time, is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place” and the driving must be such that it amounts to “a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the accused’s circumstances”; while the offence under s.219 requires “a marked and substantial departure from the standard of a reasonable driver in circumstances” where the accused “showed a reckless disregard for the lives and safety of others” (R. v. Sharp (1984), 12 CCC(3d) 428 Ont CA).

On a review of all of the evidence, while it is clear that the two police vehicles were travelling at speeds well in excess of the posted speed limit, I accept that there was little vehicular and no pedestrian traffic, the weather and driving conditions were good, and that the police officers had observed Complainant #1 to commit a criminal act in striking SO #1 with his motor vehicle.

I also find that while Complainant #1’s manner of driving posed an immediate and significant danger to others motorists, it appears that the dangerous nature of his driving preceded the police pursuit, in that even prior to the four police officers entering their police vehicles with the intention of either stopping and investigating the driver for a criminal offence, or determining if he was fit to drive, Complainant #1 drove off at a significant rate of speed, struck SO #1, and to a lesser degree WO #2, and then drove in such a manner as to put other motorists at risk, in his efforts to avoid both the RIDE check and to flee from police. When Complainant #1 then later resorted to driving either on the wrong side of the road, or the wrong way on one way streets, narrowly avoiding several head-on collisions, his driving put the public at such a high risk that the consideration of public safety dictated that he had to be apprehended and stopped.

Additionally, I find that there is no evidence that the driving, by any of the police officers, created a danger to other users of the roadway or that at any time they interfered with other traffic, other than that their approach caused other motorists to pull over to the side of the road, as required by law.

On all of the evidence before me, I cannot find any connection between the actions of the police in attempting to stop Complainant #1, who was a clear and imminent danger to the lives of others, and the injuries sustained by Complainant #2 and Complainant #1 himself. On this record, it is clear that Complainant #1 chose to drive in a manner which was dangerous to others and that he had no regard for the possible loss of life that his driving could lead to, both before and after the police initiated a vehicular pursuit.

I find that the four police officers engaged in the vehicular pursuit, to attempt to either stop and/or identify the driver of the Traverse, as well as SO #2, who was monitoring the pursuit, used their best efforts in what was a very fast paced and dynamic situation, with little time for planning out strategies. Specifically, I find that the constant communication between the involved police officers and the dispatcher, wherein they provided all available information about the pursuit and the subject vehicle, as well as the repeated and urgent demands by SO #1 for the assistance of uniformed units from various police services, indicates that they were very aware of their obligations during a pursuit and they were making every effort to comply and to bring the pursuit to an end as quickly and safely as possible.