SIU Director’s Report - Case # 18-PVI-140

Warning:

This page contains graphic content that can shock, offend and upset.

Contents:

Mandate of the SIU

The Special Investigations Unit is a civilian law enforcement agency that investigates incidents involving police officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The Unit’s jurisdiction covers more than 50 municipal, regional and provincial police services across Ontario.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Information restrictions

Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (“FIPPA”)

Pursuant to section 14 of FIPPA (i.e., law enforcement), certain information may not be included in this report. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:- Confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by law enforcement agencies; and

- Information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding.

- Subject Officer name(s);

- Witness Officer name(s);

- Civilian Witness name(s);

- Location information;

- Witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence; and

- Other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation.

Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 (“PHIPA”)

Pursuant to PHIPA, any information related to the personal health of identifiable individuals is not included. Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from this report because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner’s inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.Mandate engaged

The Unit’s investigative jurisdiction is limited to those incidents where there is a serious injury (including sexual assault allegations) or death in cases involving the police.

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the serious injuries sustained by a 36-year-old man (Complainant #1) and a 24-year-old man (Complainant #2) following a police pursuit on May 11, 2018.

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the serious injuries sustained by a 36-year-old man (Complainant #1) and a 24-year-old man (Complainant #2) following a police pursuit on May 11, 2018.

The Investigation

Notification of the SIU

At approximately 4:24 am on May 11, 2018, the OPP notified the SIU of a motor vehicle collision (MVC), following a police pursuit, at the intersection of Kipling Avenue and Steeles Avenue West in the City of Toronto. The OPP reported that at approximately 2:03 am, OPP officers were operating a Reduce Impaired Driving Everywhere (RIDE) spot check program at Highway (Hwy) 410 and Steeles Avenue West in Toronto, when a motor vehicle struck two of the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) officers conducting the program and then fled. The police officers sustained minor injuries. The police officers pursued and lost sight of the vehicle. Officers were then directed by citizens to a collision scene located at Kipling Avenue and Steeles Avenue West involving the previously pursued motor vehicle. At the time of the notification, two males were in hospital; one with a broken arm and one with head injuries. The scene was being held for the SIU.

The Team

Number of SIU Investigators assigned: 4

Number of SIU Forensic Investigators assigned: 3

Number of Collision Reconstructionists: 1

Number of Collision Reconstructionists: 1

Complainants:

Complainant #1 36-year-old male interviewed, medical records obtained and reviewed Complainant #2 25-year-old male interviewed, medical records obtained and reviewed

Civilian Witnesses

No civilian witnesses were identified, nor did any come forward to provide information.Witness Officers

WO #1 Interviewed, notes received and reviewedWO #2 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #3 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #4 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #5 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

Subject Officers

SO #1 Declined interview and to provide notes, as is the subject officer’s legal rightSO #2 Declined interview, as is the subject officer’s legal right. Notes received and reviewed.

Incident Narrative

At approximately 1:47 am on May 11, 2018, police officers from the Toronto OPP Detachment, SO #1, WO #1, WO #2, and WO #3, were conducting RIDE spot checks at Hwy 410 and Queen Street in the City of Brampton when a Chevrolet Traverse SUV motor vehicle drove through the spot check area without stopping. Although the vehicle initially slowed, when the officers approached, the Traverse sped off striking SO #1 in the shoulder/arm area. The police officers then entered two separate police vehicles and pursued the Traverse. SO #1 was driving the first police vehicle, followed by WO #2 driving the second.

Both police vehicles engaged the Traverse in a vehicular pursuit, with the intention of stopping the vehicle and investigating the driver for possibly impaired driving, as well as for dangerous driving and assault with a weapon, for striking and injuring SO #1. At one point, the officers lost sight of the Traverse, but later located it near the dead end of Kipling Avenue, north of Steeles Avenue West, after it had apparently been involved in a single vehicle collision. Both the driver, Complainant #1, and the passenger, Complainant #2, were removed from the motor vehicle and arrested, following which they were taken to hospital.

SO #2, the Communications Supervisor, monitored the pursuit from the Communications Centre at OPP Headquarters in Orillia and was responsible for ensuring that the pursuit was conducted appropriately and did not endanger the public. At no time did SO #2 direct the police officers involved to terminate the vehicular pursuit.

Nature of Injuries/Treatment

Following a Computerized Tomography (CT) scan, Complainant #1 was diagnosed with a small intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding inside the brain or skull), an L3L4 transverse process (a bony protrusion from the back of a vertebrae bone in the spine) fracture, a retrosternal hematoma (bleeding behind the sternum), and a lung contusion, and was referred to a specialist for follow up.

Complainant #2 also had a CT scan, following which he was diagnosed with a nasal bone fracture, a left humerus head (where the long bone in the arm connects to the body) fracture, and a left shoulder dislocation, for which he was also referred to a specialist for follow up.

Both police vehicles engaged the Traverse in a vehicular pursuit, with the intention of stopping the vehicle and investigating the driver for possibly impaired driving, as well as for dangerous driving and assault with a weapon, for striking and injuring SO #1. At one point, the officers lost sight of the Traverse, but later located it near the dead end of Kipling Avenue, north of Steeles Avenue West, after it had apparently been involved in a single vehicle collision. Both the driver, Complainant #1, and the passenger, Complainant #2, were removed from the motor vehicle and arrested, following which they were taken to hospital.

SO #2, the Communications Supervisor, monitored the pursuit from the Communications Centre at OPP Headquarters in Orillia and was responsible for ensuring that the pursuit was conducted appropriately and did not endanger the public. At no time did SO #2 direct the police officers involved to terminate the vehicular pursuit.

Nature of Injuries/Treatment

Following a Computerized Tomography (CT) scan, Complainant #1 was diagnosed with a small intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding inside the brain or skull), an L3L4 transverse process (a bony protrusion from the back of a vertebrae bone in the spine) fracture, a retrosternal hematoma (bleeding behind the sternum), and a lung contusion, and was referred to a specialist for follow up. Complainant #2 also had a CT scan, following which he was diagnosed with a nasal bone fracture, a left humerus head (where the long bone in the arm connects to the body) fracture, and a left shoulder dislocation, for which he was also referred to a specialist for follow up.

Evidence

The Scene

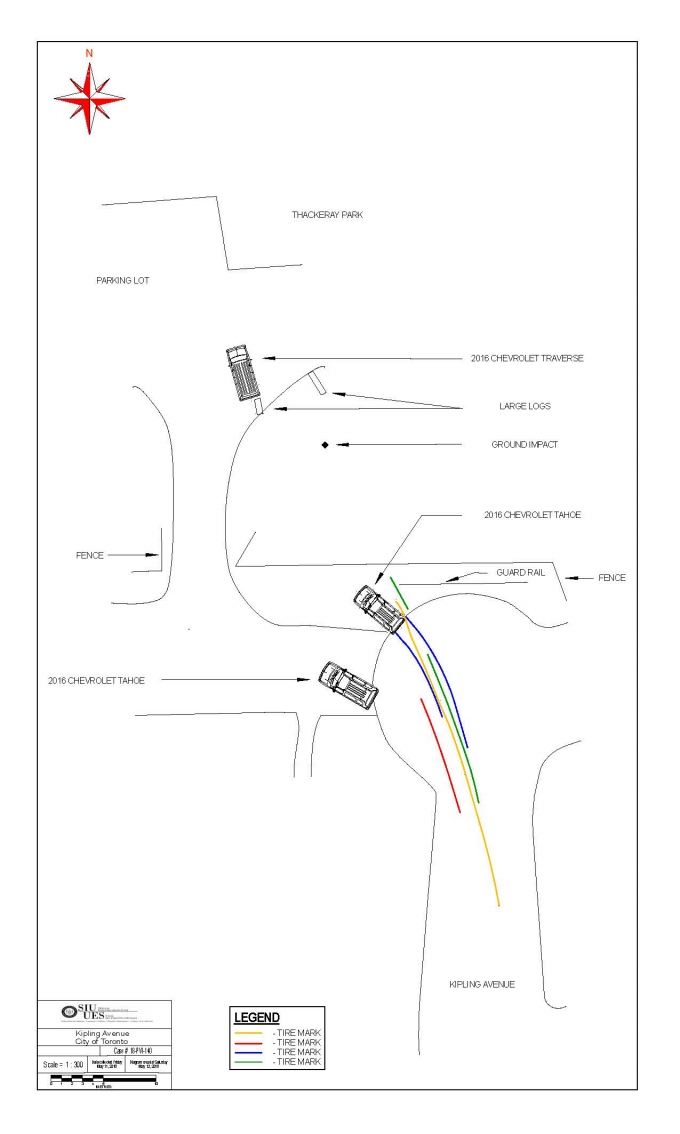

The scene was at the dead end of Kipling Avenue, about 100 meters north of Steeles Avenue West, in the City of Toronto. The dead end had a concrete curb and there was a chain link fence just north of the dead end. There was damage to the fence consistent with the Traverse having driven through it.There was a ditch just north of the chain link fence. Marks and gouges in the ditch were located consistent with the Traverse having driven through the ditch and colliding heavily with the ground on the north side of the ditch.

There were a number of large logs separating the parking lot from the ditch. Several were displaced, which was found to have been consistent with having been struck by the Traverse as it came out of the ditch and before coming to rest in the parking lot of the park, facing generally north.

The intersection of Kipling Avenue and Steeles Avenue West was controlled by a traffic light. On the south side of Steeles Avenue West, and on both sides of Kipling Avenue, there were large apartment buildings; on the northwest corner of the intersection there was a gas station and, on the northeast corner, there was a field.

The road surface on Kipling Avenue, north of the intersection, was paved asphalt without markings. The speed limit was an unposted 50 km/h. A gravel driveway extended to the west at the dead end, leading to the parking lot of the park, and provided access to businesses on the south side of Steeles Avenue West.

Pursuit Route

The pursuit route was videotaped and the route taken was as follows:

- Start at the southbound Hwy 410 on-ramp from Queen Street eastbound lanes in Brampton, then on the southbound Hwy 410 off-ramp to Steeles Avenue;

- Exit Hwy 410 at Steeles Avenue;

- Turn left off of the exit ramp onto Steeles Avenue to travel to Airport Road; a light industrial/commercial area;

- Right turn onto Airport Road to Morningstar Drive; a commercial/residential area;

- Left turn onto Morningstar Drive to Humberwood Boulevard; a residential area;

- Right turn onto Humberwood Boulevard to Rexdale Boulevard; a residential area;

- Right turn onto Rexdale Boulevard to Rexwood Road;

- Left turn onto Rexwood Road to Nashua Drive; a residential area;

- Right turn onto Nashua Drive to Goreway Drive; a light industrial area;

- Left turn onto Goreway Drive to Belfield Road; a light industrial area;

(Note: Goreway Drive changes to Disco Road and then to Attwell Drive before reaching Belfield Road.)

- Left turn onto Belfield Road to Kipling Avenue; a light industrial area;

- Left turn onto Kipling Avenue to dead end; a commercial/residential area;

- End of route completed at dead end of Kipling Avenue, north of Steeles Avenue West.

The entire route was approximately 32.8 km in length. The route took approximately 30 minutes to complete, when driving at the speed limits.

The Collision scene is located in the centre of the photo, just past the two parked police cruisers.

The Traverse after it came to rest.

Scene Diagram

Physical Evidence

The Traverse driven by Complainant #1 with Complainant #2 as passenger.

Traverse in foreground, after having travelled through the fence, the ditch, and coming to rest; the two police SUVs are seen in the background, having come to a stop before the fence.

Route taken by Traverse after coming through fence.

Gouge marks made by the Traverse

Gouge marks made by the Traverse

Crash Data Retrieval (CDR)

The CDR report was obtained from the Traverse, the SO #1’s police vehicle, and the police vehicle operated by WO #2.The CDR data indicated that the Traverse decelerated from a speed of 147km/h, five seconds prior to impact, and from a speed of 28 km/h, one half second prior to impact with the curb at the north side of the dead end at Kipling Avenue.

The CDR data indicated that the Traverse continued to brake and decelerate for about two seconds, and was travelling approximately 11 km/h one half second prior to when it struck the ditch in the park.

No CDR event data was recovered from either OPP police vehicles as there were no air bag deployments from either vehicle.

The damage to SO #1’s police vehicle was caused from the collision with a fire hydrant.

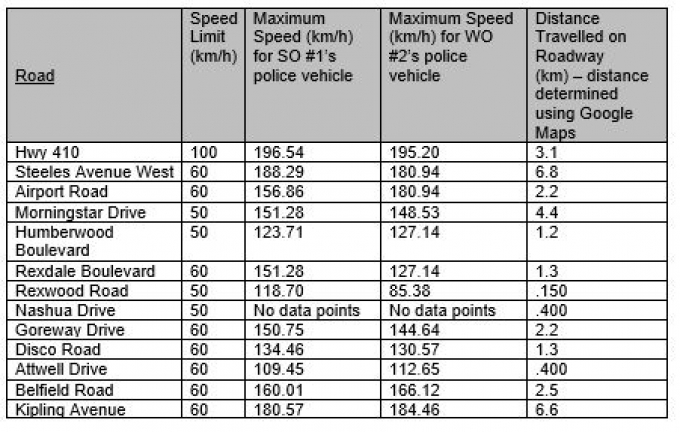

Global Positioning Service (GPS) Data.

GPS data was obtained for the OPP police vehicles operated by SO #1 and WO #2. The chart below shows the maximum speeds reached by the OPP vehicles, the speed limits, and the distance traveled on each road during the pursuit, where the information was available.

Forensic Evidence

No submissions were made to the Centre of Forensic Sciences.Expert Evidence

Collision Reconstruction Follow-Up Report

The SIU Collision Reconstructionist examined the scene and vehicles. The following is a summary of the physical evidence acquired from the Reconstructionist follow-up report: The tire marks from the Traverse were consistent with slight counter clockwise rotation of the Traverse as it approached and struck the curb at the north end of the dead end of Kipling Avenue. The rotation was consistent with steering input from the driver turning to the left in order to avoid colliding head-on with the metal guardrail.

Tire strikes were found on the north curb consistent with the Traverse having struck the curb. Tire marks were found in the grass leading to the chain link fence which were consistent with the Traverse travelling about 6 meters on the grass prior to going through the fence.

The Traverse then continued into a ditch, where the front end struck the ground on the north side of the ditch, after which it continued in a northerly direction out of the ditch, striking a row of large logs which were about 6 meters north of the bottom of the ditch.

The Traverse came to rest in the parking lot, having travelled about 60 meters since the first tire mark on Kipling Avenue, north of Steeles Avenue West.

Tire marks leading directly to the final resting position of the black OPP vehicle were consistent with the driver of the black OPP vehicle having turned sharply to the left, nearing the north curb of the dead end, in an attempt to travel onto the driveway which was to the west.

If not for the fire hydrant, the black OPP vehicle would likely have stopped uneventfully in about the same spot.

Video/Audio/Photographic Evidence

CCTV

Bus Stop H, located on Steeles Avenue West and Dixie Road (eastbound stop only)

- At 0148:43 hrs, a silver grey SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove eastbound on Steeles Avenue West, in the right lane;

- At 0148:50 hrs, a black SUV, believed to be SO #1’s police vehicle, followed in the right lane without its emergency lighting system activated;

- At 0148:55 hrs, a light coloured SUV, believed to be the OPP vehicle operated by WO #2, followed in the centre lane without its emergency lighting system activated;

- There was little traffic at the time and all three vehicles were observed driving at greater speeds than the other vehicles observed.

Bus Stop I, located on Steeles Avenue West and Bramalea Road (eastbound and westbound stops)

- At 01:49:09 hrs, a silver grey SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove eastbound on Steeles Avenue West, in the left lane;

- At 01:49:19 hrs, a black SUV, believed to be SO #1’s police vehicle, followed in the right lane, with its emergency lighting system activated;

- At 01:49:23 hrs, a light coloured SUV, believed to be the police vehicle driven by WO #2, followed with its lighting system activated;

- There was little traffic at the time and all three vehicles were seen to be driving at speeds greater than the other vehicles observed.

Bus Stop J, located eastbound on Steeles Avenue West and Torbram Road (eastbound and westbound stops)

- At 01:49:46 hrs, a silver grey SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove eastbound on Steeles Avenue West, in the right lane;

- An unidentified white SUV was seen driving in the centre lane, approximately ten meters behind the Traverse and at the same rate of speed;

- At 01:49:53 hrs, a black SUV, believed to be the police vehicle operated by SO #1, followed in the right lane with its emergency lighting system activated;

- An unidentified black sedan was seen driving in the centre behind these two vehicles, at a slower rate of speed;

- At 01:49:55 hrs, a light coloured SUV, believed to be the police vehicle driven by WO #2, followed in the left lane at speeds greater than the other vehicles and with its emergency lighting system activated;

- Little traffic was observed and the three identified vehicles were driving faster than the other vehicles observed, with the exception of the unidentified white SUV.

Bus Stop K, located westbound on Steeles Avenue West and Airport Road (eastbound and westbound stops)

- At 01:50:13 hrs, a silver grey SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove eastbound on Steeles Avenue West;

- At 01:50:17 hrs, a black SUV, believed to be the police vehicle operated by SO #1, followed with its emergency lighting system activated;

- At 01:50:20 hrs, a light coloured SUV, believed to be the police vehicle driven by WO #2, followed without its emergency lighting system activated;

- There was little traffic observed at the time and all three vehicles were driving faster than the other vehicles observed;

- The white SUV and the black sedan mentioned above slowed and continued on Steeles Avenue West.

Tim Hortons, 7480 Airport Road

Camera 9 was the only camera with a good view of Airport Road.- At 01:51:05 hrs, a silver grey SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove southbound on Airport Road in the northbound lane (wrong way);

- At 01:51:07 hrs, a light coloured SUV with red and blue blinking emergency lights on, believed to be the police vehicle operated by SO #1, followed driving southbound in the proper southbound lane;

- At 01:51:10 hrs, a black SUV with red and blue blinking emergency lights on, believed to be the police vehicle operated by WO #2, followed driving southbound in the northbound lane (wrong way);

- There was little traffic at the time and all three vehicles were driving faster than the other vehicles observed.

Malton Community Centre, 3540 Morningstar Drive

- At 01:52:12 hrs, a SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove eastbound at high speed on Morning Star Drive;

- At 01:52:15 hrs, an SUV with blinking lights, believed to be an OPP SUV, followed;

- At 01:52:25 hrs, another SUV with blinking lights, believed to be another OPP SUV, followed;

- It was not possible to identify or describe the vehicles from this video due to the distance between the camera and the road.

680 Rexdale Boulevard

Channel 1 (pointing toward Humberwood Boulevard, 80 metres north of the intersection with Rexdale Boulevard)

- At approximately 01:53:38 hrs, a silver grey SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove southbound on Humberwood Boulevard;

- At approximately 01:53:44 hrs, a light grey SUV with red and blue emergency lights on, believed to be the OPP vehicle operated by WO #2, followed;

- At approximately 01:53:49 hrs, a black SUV with red and blue emergency lights on, believed to be the OPP vehicle operated by SO #1, followed;

- The traffic on Humberwood Boulevard was light at the time.

6889 Rexwood Road

Channel 7 (pointing towards Derry Road East and Rexwood Road)

- At 01:54:44 hrs, a silver grey SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, was driving westbound on Derry Road East and turned left (south) at high speed onto Rexwood Road, then drove southbound in the right lane;

- At 01:54:46 hrs, a dark SUV and a light coloured SUV with red and blue blinking lights, believed to be the police vehicles operated by SO #1 and WO #2, followed immediately behind. The vehicles were driving side by side, with the SO’s vehicle on the right and WO #2’s vehicle on the left;

- The traffic light was green on Derry Road East as all three vehicles turned left onto Rexwood Road. There was some traffic travelling eastbound on Derry Road with all the other vehicles having stopped just before the three identified vehicles crossed the intersection. There was no traffic westbound until after the identified SUVs had crossed.

Channel 1 and 4 (pointing towards Rexwood Road)

- At 01:54:55 hrs, a light coloured SUV, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove southbound on Rexwood Road, in the left lane;

- At 01:54:57 hrs, two SUVs with blinking lights, believed to be the police vehicles operated by SO #1 and WO #2, followed approximately 30 meters behind the Traverse. The vehicles were driving side by side in both lanes, with SO #1’s police vehicle in the right lane and WO #2’s vehicle in the oncoming lane of traffic.

3965 Nashua Drive

(The quality of this video was very poor.)- At 01:54:58 hrs, a vehicle, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove southbound on Rexwood Road and slowed just before the intersection with Nashua Drive;

- At 01:55:00 hrs, two vehicles, believed to be the two OPP vehicles, followed and also slowed.

441 Carlingview Drive

(The quality of this video was not clear enough to positively identify any vehicles.)- At approximately 01:57:07 hrs, a vehicle, believed to be Complainant #1’s Traverse, drove eastbound on Disco Road, in the left lane;

- At approximately 01:57:11 hrs, a dark SUV with blinking lights, believed to be SO #1’s police vehicle, followed on the left lane. At approximately 01:57:17 hrs, a light coloured SUV with blinking lights, believed to be the police vehicle operated by WO #2, followed in the left lane.

Several additional videos were obtained from the OPP which were consistent with the above.

Communications Recordings

PCC Recordings

- At 01:47:10 hrs, a female officer said that a vehicle failed to stop at a RIDE spot check;

- At 01:47:24 hrs, a female officer said the vehicle hit her left arm (presumably this was SO #1). The vehicle was southbound on Hwy 410 in “lane 3” exiting at Steeles Avenue; she asked for Peel Regional Police (PRP) to be advised;

- At 01:47:55 hrs, a OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC dispatcher asked for the vehicle description. A male officer said the vehicle was a Chevrolet SUV and provided a partial licence plate;

- At 01:48:30 hrs, a male officer provided a description of the driver’s skin colour;

- At 01:48:50 hrs, a male officer said eastbound on Steeles Avenue;

- At 01:49:02hrs, the male officer said they were passing Advance Boulevard;

- At 01:49:17 hrs, the male officer said they were passing Bramalea Road;

- At 01:49:53 hrs, the male officer said they were passing Torbram Road;

- At 01:49:58 hrs, the OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC dispatcher asked for the speed;

- At 01:50:09 hrs, the male officer said, “182;”

- At 01:50:11 hrs, SO #2 asked if the vehicle was wanted for going through the RIDE stop.

- At 01:50:18 hrs, a male officer said the vehicle hit one officer. The male said they were southbound on Airport Road;

- At 01:50:30 hrs, a female officer said the vehicle hit two officers;

- At 01:50:58 hrs, a male officer reported the vehicle was on Airport Road going the wrong way;

- At 01:51:25 hrs, the vehicle was reported as travelling east on Morningstar Drive;

- At 01:51:36 hrs, the OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC dispatcher asked for a vehicle description;

- At 01:51:42 hrs, a male officer said it was a Silver Chevrolet SUV;

- At 01:52:31 hrs, a female officer said they were passing Darcel Avenue at 136 km? and possibly more;

- At 01:52:54 hrs, a female officer said she needed PRP now;

- At 01:53:04 hrs, the OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC dispatcher said they were online with PRP. A male officer said they were turning right on Humberwood Boulevard and the vehicle was going the wrong way;

- At 01:54:19 hrs, a female officer provided a complete licence plate number for the vehicle;

- At 01:54:37 hrs, it was reported that they were approaching Rexwood Road;

- At 01:54:46 hrs, left on Rexwood Road going south.

- At 01:54:54 hrs, passing Nashua Drive.

- At 01:55:05 hrs, WO #2 was told by a male officer to stay back;

- At 01:55:13 hrs, right on Nashua Drive;

- At 01:55:47 hrs, a male officer asked for information on the licence plate;

- At 01:55:56 hrs, the OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC dispatcher said the plate was registered to a female party;

- At 01:56:07 hrs, the male officer said it was going to be a male driver;

- At 01:57:07 hrs, a male officer indicated east on Belfield Road and that Toronto Police Service (TPS) were needed. They were approaching Hwy 427;

- At 01:57:20 hrs, they were on Belfield Road at City View Drive, approaching Hwy 27;

- At 01:57:36 hrs, the OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC dispatcher asked for their location and that the TPS was “patching in;”

- At 01:57:41 hrs, eastbound Belfield Road passing Iron Street;

- At 01:58:18 hrs, northbound Kipling Avenue;

- At 01:58:32 hrs, approaching Rexdale Boulevard. Going the wrong way;

- At 01:59:31 hrs, northbound passing Brookmere Road;

- At 01:59:45 hrs, approaching Albion Road;

- At 02:00:04 hrs, passing Albion Road;

- At 02:00:12 hrs, approaching Finch Avenue;

- At 02:00:52 hrs, approaching Hwy 407. Advise Hwy 407 officers;

- At 02:01:22 hrs, at Steeles Avenue;

- At 02:01:59 hrs, a female officer screamed, “…get your fucking hands….”;

- At 02:02:36 hrs, a female officer reported, “I crashed. He crashed. Two bodies inside;”

- At 02:02:52 hrs, a female officer reported that they had two prisoners. The dispatcher asked for the location;

- At 02:03:01 hrs, a female officer said they had two males and they needed a sergeant, and that they will probably need to call the SIU;

- At 02:03:34 hrs, the female officer said they were at Thackeray Park Cricket Grounds; and,

- At 02:04:23 hrs, the female officer requested an ambulance.

On the OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC phones, SO #2, the OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC Supervisor, was recorded as indicating that he was monitoring the pursuit. Attempts were made to get a helicopter, but none were available.

Materials obtained from Police Service

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the OPP:- Police Transmission Communications Recordings;

- Recordings of Telephone Calls of SO #2 on OPP Provincial Communications Centre ">PCC phones, during the pursuit;

- Scene Video;

- Photos of Traverse, later determined to be a stolen motor vehicle;

- 11 CCTV videos provided by OPP from premises on route of pursuit;

- Aerial Photos;

- Affidavits of the OPP Technical Analyst (x4) re: downloaded data from police vehicles;

- Arrest Report (Complainant #1);

- Crown Brief Synopsis for charges against Complainant #1;

- Prepared Diagrams (x3);

- Event Details Report;

- Fail to Stop Report;

- General Report;

- GPS Gate Data Table for the police vehicles operated by SO #1 and WO #2;

- List of Involved Officers;

- Mobile Public Safety (MPS) Data Tables for the police vehicles operated by SO #1 and WO #2;

- Crash Data Retrieval (CDR) reports for Traverse and both involved police vehicles;

- Notes of WO #s 1-3 and SO #2;

- Preliminary Collision Reconstruction Report prepared by OPP officers;

- Notes of officers involved in preparation and investigation of Collision Reconstruction (x6) and deployment of drone;

- Final OPP Collision Reconstruction Report;

- OPP Scene Photos;

- OPP Unmanned Aerial Surveillance (UAS) Pre-Flight Checklist Report;

- OPP Witness Statement from undesignated witness re: stolen licence plates on Traverse;

- Quality Report (Steeles report) for UAS;

- Training Records for WO #s 1-3 and SO #1;

- Vehicle Damage Report; and,

- Vehicle Exam Field Notes for the Traverse and the police vehicles operated by WO #2 and SO #1.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from other sources:

- Medical Records of Complainants #1 and 2 relating to this event, obtained with their consent; and,

- CCTV video from 10 Commercial Premises, three City Buses, and four bus stops.

Relevant Legislation

Sections 1-3, Ontario Regulation 266/10, Ontario Police Services Act -- Suspect Apprehension Pursuits

1. (1) For the purposes of this Regulation, a suspect apprehension pursuit occurs when a police officer attempts to direct the driver of a motor vehicle to stop, the driver refuses to obey the officer and the officer pursues in a motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle or identifying the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle.

(2) A suspect apprehension pursuit is discontinued when police officers are no longer pursuing a fleeing motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle or identifying the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle.

2. (1) A police officer may pursue, or continue to pursue, a fleeing motor vehicle that fails to stop,

(a) if the police officer has reason to believe that a criminal offence has been committed or is about to be committed; or(b) for the purposes of motor vehicle identification or the identification of an individual in the vehicle.

(2) Before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall determine that there are no alternatives available as set out in the written procedures of,

(a) the police force of the officer established under subsection 6 (1), if the officer is a member of an Ontario police force as defined in the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009;(b) a police force whose local commander was notified of the appointment of the officer under subsection 6 (1) of the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, if the officer was appointed under Part II of that Act; or(c) the local police force of the local commander who appointed the officer under subsection 15 (1) of the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, if the officer was appointed under Part III of that Act.

(3) A police officer shall, before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, determine whether in order to protect public safety the immediate need to apprehend an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle or the need to identify the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle outweighs the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit.

(4) During a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall continually reassess the determination made under subsection (3) and shall discontinue the pursuit when the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit outweighs the risk to public safety that may result if an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not immediately apprehended or if the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not identified.

(5) No police officer shall initiate a suspect apprehension pursuit for a non-criminal offence if the identity of an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is known.

(6) A police officer engaging in a suspect apprehension pursuit for a non-criminal offence shall discontinue the pursuit once the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is identified.

3. (1) A police officer shall notify a dispatcher when the officer initiates a suspect apprehension pursuit.

(2) The dispatcher shall notify a communications supervisor or road supervisor, if a supervisor is available, that a suspect apprehension pursuit has been initiated

Section 219 and 221, Criminal Code -- Criminal negligence causing bodily harm

219 (1) Every one is criminally negligent who

(a) in doing anything, or(b) in omitting to do anything that it is his duty to do,

shows wanton or reckless disregard for the lives or safety of other persons.

(2) For the purposes of this section, duty means a duty imposed by law.

Section 249 (1) and (3), Criminal Code -- Dangerous operation of motor vehicles causing bodily harm

249 (1) Every one commits an offence who operates

(a) a motor vehicle in a manner that is dangerous to the public, having regard to all the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that at the time is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place(3) Every one who commits an offence under subsection (1) and thereby causes bodily harm to any other person is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years.

Analysis and Director's Decision

On May 11, 2018, at approximately 1:47 a.m., Subject Officer (SO) #1, Witness Officer (WO) #1, WO #2, and WO #3, of the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) Port Credit Highway Safety Division, were set up conducting RIDE (Reduce Impaired Driving Everywhere) spot checks at the ramp from Queen Street East to Highway 410 in the City of Brampton. SO #1 was partnered with WO #1 and they were travelling in a black SUV police vehicle with subdued markings, while WO #2 and WO #3 were in an unmarked light coloured SUV. While conducting the spot check, a silver Traverse motor vehicle was observed to slow for the RIDE spot check and hesitate, but did not stop. As the police officers approached the vehicle, the Traverse drove off, striking SO #1 in the shoulder as it did so. Immediately thereafter, all four of the RIDE police officers entered their respective vehicles and pursued the Traverse; the pursuit ended when the Traverse crashed through a fence, following which it struck the side of a ditch, before coming to a stop inside the fenced area of the Thackeray Park Cricket Grounds, at the dead end of Kipling Avenue, just north of Steeles Avenue West, in the City of Toronto.

At the time that the vehicle finally came to rest, after the pursuit and subsequent single vehicle collision, the driver, Complainant #1, and his passenger, Complainant #2, were removed from the vehicle and arrested; both were then transported to the hospital where it was discovered that Complainant #1 had sustained a brain bleed, a spinal fracture, bleeding under the sternum, and a lung contusion, while Complainant #2 had sustained a broken nose and a broken bone in his left shoulder, and had dislocated his shoulder.

During the course of this investigation, both Complainant #2 and Complainant #1 provided interviews to the SIU, as did five police witnesses. With respect to the two subject officers, SO #1, who was driving the lead pursuit vehicle during the Suspect Apprehension Pursuit (SAP), declined to be interviewed or to provide her memorandum books notes for review, while SO #2, the Communications Supervisor who was monitoring the SAP, provided his notes but declined to be interviewed; as subject officers, this was within their legal rights.

Due to the time of day when this incident occurred, being at 1:47 a.m., and the fact that the incident began at the ramp to Highway 410 and concluded at the dead end of Kipling Avenue, not surprisingly, an appeal for civilian witnesses garnered no results and none came forward to provide statements.

SIU investigators also reviewed the memo book notes of all witness officers, the GPS/MPS data from the two involved police cruisers, the police radio transmissions leading up to and throughout the pursuit, the CDR data from the vehicle driven by Complainant #1, and various CCTV footage from premises along the pursuit route. With the exception as to how many persons were inside the Traverse during the pursuit, and whether or not Complainant #1 initially stopped his motor vehicle at the RIDE program, there is very little disagreement between the statements of the occupants of the Traverse and the officers who were involved in the pursuit, or who monitored the pursuit. The following narrative is based on the credible and reliable evidence obtained during the investigation.

At approximately 1:47 a.m., Complainant #1 was operating a Traverse SUV eastbound on Queen Street East in the City of Brampton and entered onto the ramp to southbound Hwy 410, when he saw a RIDE check on the ramp; Complainant #2 was seated in the motor vehicle. While both Complainant #1 and Complainant #2 claim that a third party was also inside the motor vehicle at the time, since it is not alleged by anyone that this third party was the driver, for my purposes, nothing really turns on this discrepancy.

The weather was clear, there was overhead lighting at the point where the stop check was located, and traffic was light.

As Complainant #1 came down the ramp to the highway, he slowed and appeared to hesitate, but did not come to a full stop. While Complainant #1 claims that he initially stopped the car at the RIDE check, and spoke to the police officers, based on the evidence of Complainant #2, who confirms the evidence of the four police officers, I find that Complainant #1 slowed, but at no time did he fully stop his motor vehicle, when directed by the officers to do so.

Complainant #1 was observed to make eye contact with the officers and appeared to be very aware of their presence. All four police officers approached the Traverse.

Three of the police officers approached the driver’s door, with WO #1 standing to their left. Complainant #1, who was on a court ordered release not to be outside of his residence at that time, decided to evade the stop check and accelerated away from the police officers. While standing near the rear of the Traverse, when the vehicle did not stop, WO #1 then struck the rear window with his flashlight, before stepping back and observing the Traverse continue and speed up. Despite Complainant #1’s denial, I accept the evidence of the four police officers, as confirmed by the injury to SO #1, and the communications recording, that in accelerating away from the attempted stop point, the Traverse struck SO #1.

At that point, all four officers ran to their respective vehicles, with SO #1 entering the driver’s seat of the black police SUV with the subdued markings, and WO #2 entering the driver’s seat of the unmarked police vehicle. As soon as they were inside their vehicle, SO #1 made WO #1 aware that she had been struck by the Traverse and that she was experiencing pain to her left shoulder.

This evidence is confirmed by the radio transmission from SO #1 at 1:47 a.m., wherein she is originally heard to report that a vehicle had failed to stop at the RIDE and then, 14 seconds later, that the vehicle had struck her left arm. SO #1 also provided the Traverse’s direction of travel as going southbound on the 410 Hwy at approximately 194 km/h and exiting at Steeles Avenue. Furthermore, SO #1 requested that the Peel Regional Police (PRP) be advised that they were immediately needed.

WO #1 is then heard to come on the radio at 1:47:55 a.m., and provide the vehicle description, along with a partial licence plate, a brief description of the driver, and its direction of travel; WO #1 then continually updated the dispatcher as new information became available. At 1:50:09 a.m., WO #1 then provided the speed of their police vehicle as travelling at 182 km/h, in an attempt to catch up to, and stop, the Traverse.

On this evidence, I find that at the time that the SAP was initiated, the four police officers had ample grounds to stop and investigate the Traverse’s driver for possible signs of impairment based on his refusal to stop at the RIDE, failing to stop for police when directed, dangerous driving causing bodily harm, and possibly assault with a weapon (the weapon being the motor vehicle itself, which was used to strike SO #1). As such, there appears ample evidence to support the decision of the police officers to initiate a police pursuit at that time, and they were clearly acting lawfully in doing so.

The communications recording provides what appears to be a simultaneous narrative of the pursuit, in that WO #1 and the other officers are continually heard to relay their location, and the location of the Traverse, as they progress, along with the speeds at which they are travelling. While WO #1 is heard to relay that one police officer had been struck by the vehicle, a female officer, possibly from the second police vehicle, then indicated that two police officers had been struck, from which I find that the second officer was referring to the front bumper of the Traverse having made contact with WO #2, who had to move out of the way to avoid being struck by the mirror, but was not injured.

It is further clear from the communications recording wherein SO #2 is heard at 1:50:11 a.m. asking the involved police officers if they were in pursuit only because the Traverse had failed to stop for the RIDE check, that from that point onwards, SO #2 was monitoring the pursuit from the OPP Headquarters in Orillia. In response to SO #2’s question, he was informed not only of the fact that an officer had been struck, but that the vehicle was now driving on the wrong side of the road. SO #2’s notes indicate that he considered these grounds sufficient to justify a pursuit.

At 1:50:58 a.m., WO #1 is heard to report that the Traverse was now driving on the wrong side of the road on Airport Road and, at 1:53:04 a.m., that the Traverse was now driving in the oncoming lane of traffic on Humberwood Boulevard. On a number of occasions, the situation was described as now being a “wrong way” situation, which is specifically referred to in the OPP policies as being a serious situation justifying immediate action by police [1].

At 1:54:19 a.m., WO #2 is heard to call in that she had just managed to obtain the full licence plate of the Traverse. Subsequent inquiries by the dispatcher, however, indicated that this licence plate was not registered to the Traverse vehicle and it was subsequently confirmed that the licence plate had in fact been reported stolen.

At 1:52:54 a.m., the radio transmission recording reveals SO #1 stating that they, “Need Peel now!” At 1:55:05 a.m., WO #1 is heard to instruct WO #2 to stay back behind their vehicle and, at 1:57:07 a.m., as they entered Toronto, WO #1 indicated that the Toronto Police were required (“Need Toronto! Need Toronto!”), and at 1:58:32 a.m., WO #1 again reported that the Traverse was driving in the oncoming lane of traffic on Rexdale Boulevard.

On each occasion when assistance was requested from another police service, the dispatcher is heard to confirm that the relevant police service had been notified and was ‘patching in,’ from which I infer that each police service was monitoring the pursuit.

At 2:00:57 a.m., the involved units are again heard requesting assistance, this time advising that they were approaching the 407 toll highway and that they needed to, “Get 407 (OPP) units here!”

At 2:01:54 a.m., it is clear from the communications recording that the collision has occurred, and within seconds, at 2:01:59 hours, SO #1 can be heard out of the vehicle yelling at the occupants of the Traverse to exit their vehicle. At 2:02:36 a.m., a request is heard for a sergeant to attend immediately, following which there are requests for ambulances and that the SIU will need to be notified.

The duration of the police pursuit appears to have been approximately 14 minutes and travelled over approximately 32.8 kilometres.

During the police pursuit, Complainant #1’s speeds were described as being as high as between 160 to 200 km/h and, specifically, on Morningstar Drive, a smaller residential street with a 50 km/h speed limit, the Traverse was estimated as travelling at 130 km/h. The Traverse was also observed to proceed through several red lights and stop signs without stopping, in addition to driving on the wrong side of the road and nearly becoming involved in several head-on collisions. From this evidence, it is clear that Complainant #1, and the Traverse he was operating, posed a serious danger of causing serious injury, if not death, to other users of the roadway.

The GPS data from the two police vehicles is consistent with their reported speeds as recorded in the communications recording, with the maximum speeds reached being 196 km/h, which was at the outset of the pursuit on the 410 Hwy with a speed limit of 100 km/h, and then decreasing.

The various CCTV recordings obtained from various premises along the pursuit route confirms that the weather was clear, traffic was light, with no pedestrian traffic being noted, and that both police vehicles had their emergency equipment activated during the pursuit, while the pursuit video confirms that the road conditions were good

The CDR data from the Traverse confirms that the vehicle was travelling at an excessive rate of speed, 147 km/h, five seconds prior to making contact with the curb at the dead end on Kipling Avenue, after which its speed sharply decreased and the driver had slowed to 28 km/h within half a second of impact, after which he continued to brake until he had slowed to 11 km/h, when the Traverse struck the ditch.

Examination of both police vehicles showed no evidence that either ever made contact with the Traverse, with the only damage being to SO #1’s vehicle, which was consistent with her having struck a fire hydrant when she came to a final stop. I note that there is no allegation by Complainant #1 that any police vehicle ever made contact with his vehicle, or that police caused him to lose control, resulting in the collision.

While Ontario Regulation 266/10, of the Ontario Police Services Act (OPSA) entitled Suspect Apprehension Pursuits, indicates that an officer in an unmarked police motor vehicle shall not engage in a SAP unless a marked police vehicle is not readily available, I note that every effort was made by the officers involved, the dispatcher, and SO #2, to have other marked units from not only the OPP, but also the PRP and the TPS, attend to take over the pursuit, but none were available in the area.

With respect to the obligations placed on officers involved in a police pursuit, I note that the requirements as set out both under the OPSA and the OPP guidelines were substantially complied with, including notifying the communications centre that a pursuit had been initiated and constantly updating the dispatcher as to speeds and location. I further note that pursuant to both the OPP policy and the OPSA, the officers had valid grounds to initiate a pursuit, initially in order to attempt to identify the motor vehicle which they had observed to commit a criminal offence, and then thereafter, despite having identified the licence plate of the motor vehicle at 1:54:19 a.m., to continue the pursuit as the situation had then progressed to a potentially “life threatening situation” in that the Traverse was travelling at high rates of speed in the oncoming lanes of traffic and posed a serious threat to the public.

According to the witness officers involved in the pursuit, it was their intention to make physical contact with the Traverse in order to bring it to a stop, which I note is further authorized under s. 9 (2) of Regulation 266/10, which authorizes intentional physical contact between a police vehicle and “a fleeing motor vehicle for the purposes of stopping it only if the officer believes on reasonable grounds that to do so is necessary to immediately protect against loss of life or serious bodily harm”. As the OPP policy specifically indicates that a vehicle being driven on the wrong side of the road is a ‘life threatening occurrence’, it is clear that physical contact, if it had occurred, would arguably be justified in these circumstances.

Despite finding that I have reasonable grounds to believe that the police officers substantially complied with the Suspect Apprehension Pursuit Policy pursuant to the OPSA, the question remains whether, on these facts, there are reasonable grounds to believe that any of the officers involved in the pursuit of the Traverse, or who were monitoring the pursuit as communications supervisor, committed a criminal offence, specifically, whether or not the driving rose to the level of being dangerous and therefore in contravention of s.249 (1) of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm contrary to s.249 (3) or if the pursuit amounted to an act of criminal negligence contrary to s.219 of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm (s.221).

The decision of the Supreme Court of Canada R v Beatty, [2008] 1 S.C.R. 49, defines s.249 as requiring that the driving be dangerous to the public, “having regard to all of the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that, at the time, is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place” and the driving must be such that it amounts to “a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the accused’s circumstances”; while the offence under s.219 requires “a marked and substantial departure from the standard of a reasonable driver in circumstances” where the accused “showed a reckless disregard for the lives and safety of others” (R v Sharp (1984), 12 CCC(3d) 428 Ont CA).

On a review of all of the evidence, while it is clear that the two police vehicles were travelling at speeds well in excess of the posted speed limit, I accept that there was little vehicular and no pedestrian traffic, the weather and driving conditions were good, and that the police officers had observed Complainant #1 to commit a criminal act in striking SO #1 with his motor vehicle.

I also find that while Complainant #1’s manner of driving posed an immediate and significant danger to others motorists, it appears that the dangerous nature of his driving preceded the police pursuit, in that even prior to the four police officers entering their police vehicles with the intention of either stopping and investigating the driver for a criminal offence, or determining if he was fit to drive, Complainant #1 drove off at a significant rate of speed, struck SO #1, and to a lesser degree WO #2, and then drove in such a manner as to put other motorists at risk, in his efforts to avoid both the RIDE check and to flee from police. When Complainant #1 then later resorted to driving either on the wrong side of the road, or the wrong way on one way streets, narrowly avoiding several head-on collisions, his driving put the public at such a high risk that the consideration of public safety dictated that he had to be apprehended and stopped.

Additionally, I find that there is no evidence that the driving, by any of the police officers, created a danger to other users of the roadway or that at any time they interfered with other traffic, other than that their approach caused other motorists to pull over to the side of the road, as required by law.

On all of the evidence before me, I cannot find any connection between the actions of the police in attempting to stop Complainant #1, who was a clear and imminent danger to the lives of others, and the injuries sustained by Complainant #2 and Complainant #1 himself. On this record, it is clear that Complainant #1 chose to drive in a manner which was dangerous to others and that he had no regard for the possible loss of life that his driving could lead to, both before and after the police initiated a vehicular pursuit.

I find that the four police officers engaged in the vehicular pursuit, to attempt to either stop and/or identify the driver of the Traverse, as well as SO #2, who was monitoring the pursuit, used their best efforts in what was a very fast paced and dynamic situation, with little time for planning out strategies. Specifically, I find that the constant communication between the involved police officers and the dispatcher, wherein they provided all available information about the pursuit and the subject vehicle, as well as the repeated and urgent demands by SO #1 for the assistance of uniformed units from various police services, indicates that they were very aware of their obligations during a pursuit and they were making every effort to comply and to bring the pursuit to an end as quickly and safely as possible.

I find, on this evidence, that the driving of the police officers involved in the pursuit and the attempt to stop the Traverse, and to apprehend Complainant #1, does not rise to the level of driving required to constitute ‘a marked departure from the norm’ and even less so ‘a marked and substantial departure from the norm’ and there is no evidence to establish any causal connection between the actions of the pursuing officers and the motor vehicle collision which resulted in the injuries to the occupants of the Traverse.

I further find that SO #2, who fully monitored the pursuit, who questioned the surrounding facts and the justification in conducting the pursuit, and who made every effort to bring in other resources to bring the pursuit to a safe end, was acting fully within the ambits not only of the responsibilities of his position, but also the requirements of both the OPSA, OPP policy, and the Criminal Code.

As such, I find that there is no evidence upon which I can form reasonable grounds to believe that a criminal offence has been committed by any of the police officers involved in the vehicular pursuit of the Traverse motor vehicle, and therefore there is no basis for the laying of criminal charges.

Date: February 20, 2019

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

At the time that the vehicle finally came to rest, after the pursuit and subsequent single vehicle collision, the driver, Complainant #1, and his passenger, Complainant #2, were removed from the vehicle and arrested; both were then transported to the hospital where it was discovered that Complainant #1 had sustained a brain bleed, a spinal fracture, bleeding under the sternum, and a lung contusion, while Complainant #2 had sustained a broken nose and a broken bone in his left shoulder, and had dislocated his shoulder.

During the course of this investigation, both Complainant #2 and Complainant #1 provided interviews to the SIU, as did five police witnesses. With respect to the two subject officers, SO #1, who was driving the lead pursuit vehicle during the Suspect Apprehension Pursuit (SAP), declined to be interviewed or to provide her memorandum books notes for review, while SO #2, the Communications Supervisor who was monitoring the SAP, provided his notes but declined to be interviewed; as subject officers, this was within their legal rights.

Due to the time of day when this incident occurred, being at 1:47 a.m., and the fact that the incident began at the ramp to Highway 410 and concluded at the dead end of Kipling Avenue, not surprisingly, an appeal for civilian witnesses garnered no results and none came forward to provide statements.

SIU investigators also reviewed the memo book notes of all witness officers, the GPS/MPS data from the two involved police cruisers, the police radio transmissions leading up to and throughout the pursuit, the CDR data from the vehicle driven by Complainant #1, and various CCTV footage from premises along the pursuit route. With the exception as to how many persons were inside the Traverse during the pursuit, and whether or not Complainant #1 initially stopped his motor vehicle at the RIDE program, there is very little disagreement between the statements of the occupants of the Traverse and the officers who were involved in the pursuit, or who monitored the pursuit. The following narrative is based on the credible and reliable evidence obtained during the investigation.

At approximately 1:47 a.m., Complainant #1 was operating a Traverse SUV eastbound on Queen Street East in the City of Brampton and entered onto the ramp to southbound Hwy 410, when he saw a RIDE check on the ramp; Complainant #2 was seated in the motor vehicle. While both Complainant #1 and Complainant #2 claim that a third party was also inside the motor vehicle at the time, since it is not alleged by anyone that this third party was the driver, for my purposes, nothing really turns on this discrepancy.

The weather was clear, there was overhead lighting at the point where the stop check was located, and traffic was light.

As Complainant #1 came down the ramp to the highway, he slowed and appeared to hesitate, but did not come to a full stop. While Complainant #1 claims that he initially stopped the car at the RIDE check, and spoke to the police officers, based on the evidence of Complainant #2, who confirms the evidence of the four police officers, I find that Complainant #1 slowed, but at no time did he fully stop his motor vehicle, when directed by the officers to do so.

Complainant #1 was observed to make eye contact with the officers and appeared to be very aware of their presence. All four police officers approached the Traverse.

Three of the police officers approached the driver’s door, with WO #1 standing to their left. Complainant #1, who was on a court ordered release not to be outside of his residence at that time, decided to evade the stop check and accelerated away from the police officers. While standing near the rear of the Traverse, when the vehicle did not stop, WO #1 then struck the rear window with his flashlight, before stepping back and observing the Traverse continue and speed up. Despite Complainant #1’s denial, I accept the evidence of the four police officers, as confirmed by the injury to SO #1, and the communications recording, that in accelerating away from the attempted stop point, the Traverse struck SO #1.

At that point, all four officers ran to their respective vehicles, with SO #1 entering the driver’s seat of the black police SUV with the subdued markings, and WO #2 entering the driver’s seat of the unmarked police vehicle. As soon as they were inside their vehicle, SO #1 made WO #1 aware that she had been struck by the Traverse and that she was experiencing pain to her left shoulder.

This evidence is confirmed by the radio transmission from SO #1 at 1:47 a.m., wherein she is originally heard to report that a vehicle had failed to stop at the RIDE and then, 14 seconds later, that the vehicle had struck her left arm. SO #1 also provided the Traverse’s direction of travel as going southbound on the 410 Hwy at approximately 194 km/h and exiting at Steeles Avenue. Furthermore, SO #1 requested that the Peel Regional Police (PRP) be advised that they were immediately needed.

WO #1 is then heard to come on the radio at 1:47:55 a.m., and provide the vehicle description, along with a partial licence plate, a brief description of the driver, and its direction of travel; WO #1 then continually updated the dispatcher as new information became available. At 1:50:09 a.m., WO #1 then provided the speed of their police vehicle as travelling at 182 km/h, in an attempt to catch up to, and stop, the Traverse.

On this evidence, I find that at the time that the SAP was initiated, the four police officers had ample grounds to stop and investigate the Traverse’s driver for possible signs of impairment based on his refusal to stop at the RIDE, failing to stop for police when directed, dangerous driving causing bodily harm, and possibly assault with a weapon (the weapon being the motor vehicle itself, which was used to strike SO #1). As such, there appears ample evidence to support the decision of the police officers to initiate a police pursuit at that time, and they were clearly acting lawfully in doing so.

The communications recording provides what appears to be a simultaneous narrative of the pursuit, in that WO #1 and the other officers are continually heard to relay their location, and the location of the Traverse, as they progress, along with the speeds at which they are travelling. While WO #1 is heard to relay that one police officer had been struck by the vehicle, a female officer, possibly from the second police vehicle, then indicated that two police officers had been struck, from which I find that the second officer was referring to the front bumper of the Traverse having made contact with WO #2, who had to move out of the way to avoid being struck by the mirror, but was not injured.

It is further clear from the communications recording wherein SO #2 is heard at 1:50:11 a.m. asking the involved police officers if they were in pursuit only because the Traverse had failed to stop for the RIDE check, that from that point onwards, SO #2 was monitoring the pursuit from the OPP Headquarters in Orillia. In response to SO #2’s question, he was informed not only of the fact that an officer had been struck, but that the vehicle was now driving on the wrong side of the road. SO #2’s notes indicate that he considered these grounds sufficient to justify a pursuit.

At 1:50:58 a.m., WO #1 is heard to report that the Traverse was now driving on the wrong side of the road on Airport Road and, at 1:53:04 a.m., that the Traverse was now driving in the oncoming lane of traffic on Humberwood Boulevard. On a number of occasions, the situation was described as now being a “wrong way” situation, which is specifically referred to in the OPP policies as being a serious situation justifying immediate action by police [1].

At 1:54:19 a.m., WO #2 is heard to call in that she had just managed to obtain the full licence plate of the Traverse. Subsequent inquiries by the dispatcher, however, indicated that this licence plate was not registered to the Traverse vehicle and it was subsequently confirmed that the licence plate had in fact been reported stolen.

At 1:52:54 a.m., the radio transmission recording reveals SO #1 stating that they, “Need Peel now!” At 1:55:05 a.m., WO #1 is heard to instruct WO #2 to stay back behind their vehicle and, at 1:57:07 a.m., as they entered Toronto, WO #1 indicated that the Toronto Police were required (“Need Toronto! Need Toronto!”), and at 1:58:32 a.m., WO #1 again reported that the Traverse was driving in the oncoming lane of traffic on Rexdale Boulevard.

On each occasion when assistance was requested from another police service, the dispatcher is heard to confirm that the relevant police service had been notified and was ‘patching in,’ from which I infer that each police service was monitoring the pursuit.

At 2:00:57 a.m., the involved units are again heard requesting assistance, this time advising that they were approaching the 407 toll highway and that they needed to, “Get 407 (OPP) units here!”

At 2:01:54 a.m., it is clear from the communications recording that the collision has occurred, and within seconds, at 2:01:59 hours, SO #1 can be heard out of the vehicle yelling at the occupants of the Traverse to exit their vehicle. At 2:02:36 a.m., a request is heard for a sergeant to attend immediately, following which there are requests for ambulances and that the SIU will need to be notified.

The duration of the police pursuit appears to have been approximately 14 minutes and travelled over approximately 32.8 kilometres.

During the police pursuit, Complainant #1’s speeds were described as being as high as between 160 to 200 km/h and, specifically, on Morningstar Drive, a smaller residential street with a 50 km/h speed limit, the Traverse was estimated as travelling at 130 km/h. The Traverse was also observed to proceed through several red lights and stop signs without stopping, in addition to driving on the wrong side of the road and nearly becoming involved in several head-on collisions. From this evidence, it is clear that Complainant #1, and the Traverse he was operating, posed a serious danger of causing serious injury, if not death, to other users of the roadway.

The GPS data from the two police vehicles is consistent with their reported speeds as recorded in the communications recording, with the maximum speeds reached being 196 km/h, which was at the outset of the pursuit on the 410 Hwy with a speed limit of 100 km/h, and then decreasing.

The various CCTV recordings obtained from various premises along the pursuit route confirms that the weather was clear, traffic was light, with no pedestrian traffic being noted, and that both police vehicles had their emergency equipment activated during the pursuit, while the pursuit video confirms that the road conditions were good

The CDR data from the Traverse confirms that the vehicle was travelling at an excessive rate of speed, 147 km/h, five seconds prior to making contact with the curb at the dead end on Kipling Avenue, after which its speed sharply decreased and the driver had slowed to 28 km/h within half a second of impact, after which he continued to brake until he had slowed to 11 km/h, when the Traverse struck the ditch.

Examination of both police vehicles showed no evidence that either ever made contact with the Traverse, with the only damage being to SO #1’s vehicle, which was consistent with her having struck a fire hydrant when she came to a final stop. I note that there is no allegation by Complainant #1 that any police vehicle ever made contact with his vehicle, or that police caused him to lose control, resulting in the collision.

While Ontario Regulation 266/10, of the Ontario Police Services Act (OPSA) entitled Suspect Apprehension Pursuits, indicates that an officer in an unmarked police motor vehicle shall not engage in a SAP unless a marked police vehicle is not readily available, I note that every effort was made by the officers involved, the dispatcher, and SO #2, to have other marked units from not only the OPP, but also the PRP and the TPS, attend to take over the pursuit, but none were available in the area.

With respect to the obligations placed on officers involved in a police pursuit, I note that the requirements as set out both under the OPSA and the OPP guidelines were substantially complied with, including notifying the communications centre that a pursuit had been initiated and constantly updating the dispatcher as to speeds and location. I further note that pursuant to both the OPP policy and the OPSA, the officers had valid grounds to initiate a pursuit, initially in order to attempt to identify the motor vehicle which they had observed to commit a criminal offence, and then thereafter, despite having identified the licence plate of the motor vehicle at 1:54:19 a.m., to continue the pursuit as the situation had then progressed to a potentially “life threatening situation” in that the Traverse was travelling at high rates of speed in the oncoming lanes of traffic and posed a serious threat to the public.

According to the witness officers involved in the pursuit, it was their intention to make physical contact with the Traverse in order to bring it to a stop, which I note is further authorized under s. 9 (2) of Regulation 266/10, which authorizes intentional physical contact between a police vehicle and “a fleeing motor vehicle for the purposes of stopping it only if the officer believes on reasonable grounds that to do so is necessary to immediately protect against loss of life or serious bodily harm”. As the OPP policy specifically indicates that a vehicle being driven on the wrong side of the road is a ‘life threatening occurrence’, it is clear that physical contact, if it had occurred, would arguably be justified in these circumstances.

Despite finding that I have reasonable grounds to believe that the police officers substantially complied with the Suspect Apprehension Pursuit Policy pursuant to the OPSA, the question remains whether, on these facts, there are reasonable grounds to believe that any of the officers involved in the pursuit of the Traverse, or who were monitoring the pursuit as communications supervisor, committed a criminal offence, specifically, whether or not the driving rose to the level of being dangerous and therefore in contravention of s.249 (1) of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm contrary to s.249 (3) or if the pursuit amounted to an act of criminal negligence contrary to s.219 of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm (s.221).

The decision of the Supreme Court of Canada R v Beatty, [2008] 1 S.C.R. 49, defines s.249 as requiring that the driving be dangerous to the public, “having regard to all of the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that, at the time, is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place” and the driving must be such that it amounts to “a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the accused’s circumstances”; while the offence under s.219 requires “a marked and substantial departure from the standard of a reasonable driver in circumstances” where the accused “showed a reckless disregard for the lives and safety of others” (R v Sharp (1984), 12 CCC(3d) 428 Ont CA).

On a review of all of the evidence, while it is clear that the two police vehicles were travelling at speeds well in excess of the posted speed limit, I accept that there was little vehicular and no pedestrian traffic, the weather and driving conditions were good, and that the police officers had observed Complainant #1 to commit a criminal act in striking SO #1 with his motor vehicle.

I also find that while Complainant #1’s manner of driving posed an immediate and significant danger to others motorists, it appears that the dangerous nature of his driving preceded the police pursuit, in that even prior to the four police officers entering their police vehicles with the intention of either stopping and investigating the driver for a criminal offence, or determining if he was fit to drive, Complainant #1 drove off at a significant rate of speed, struck SO #1, and to a lesser degree WO #2, and then drove in such a manner as to put other motorists at risk, in his efforts to avoid both the RIDE check and to flee from police. When Complainant #1 then later resorted to driving either on the wrong side of the road, or the wrong way on one way streets, narrowly avoiding several head-on collisions, his driving put the public at such a high risk that the consideration of public safety dictated that he had to be apprehended and stopped.

Additionally, I find that there is no evidence that the driving, by any of the police officers, created a danger to other users of the roadway or that at any time they interfered with other traffic, other than that their approach caused other motorists to pull over to the side of the road, as required by law.

On all of the evidence before me, I cannot find any connection between the actions of the police in attempting to stop Complainant #1, who was a clear and imminent danger to the lives of others, and the injuries sustained by Complainant #2 and Complainant #1 himself. On this record, it is clear that Complainant #1 chose to drive in a manner which was dangerous to others and that he had no regard for the possible loss of life that his driving could lead to, both before and after the police initiated a vehicular pursuit.

I find that the four police officers engaged in the vehicular pursuit, to attempt to either stop and/or identify the driver of the Traverse, as well as SO #2, who was monitoring the pursuit, used their best efforts in what was a very fast paced and dynamic situation, with little time for planning out strategies. Specifically, I find that the constant communication between the involved police officers and the dispatcher, wherein they provided all available information about the pursuit and the subject vehicle, as well as the repeated and urgent demands by SO #1 for the assistance of uniformed units from various police services, indicates that they were very aware of their obligations during a pursuit and they were making every effort to comply and to bring the pursuit to an end as quickly and safely as possible.

I find, on this evidence, that the driving of the police officers involved in the pursuit and the attempt to stop the Traverse, and to apprehend Complainant #1, does not rise to the level of driving required to constitute ‘a marked departure from the norm’ and even less so ‘a marked and substantial departure from the norm’ and there is no evidence to establish any causal connection between the actions of the pursuing officers and the motor vehicle collision which resulted in the injuries to the occupants of the Traverse.

I further find that SO #2, who fully monitored the pursuit, who questioned the surrounding facts and the justification in conducting the pursuit, and who made every effort to bring in other resources to bring the pursuit to a safe end, was acting fully within the ambits not only of the responsibilities of his position, but also the requirements of both the OPSA, OPP policy, and the Criminal Code.

As such, I find that there is no evidence upon which I can form reasonable grounds to believe that a criminal offence has been committed by any of the police officers involved in the vehicular pursuit of the Traverse motor vehicle, and therefore there is no basis for the laying of criminal charges.

Date: February 20, 2019

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Endnotes

- 1) OPP ORDERS: DRIVE WRONG WAY OCCURRENCES: Deemed Life Threatening Occurrences Responsibilities: A report of a motor vehicle being driven in the wrong direction on a divided highway endangering other drivers on the roadway shall be considered a life threatening occurrence. [Back to text]

Note:

The signed English original report is authoritative, and any discrepancy between that report and the French and English online versions should be resolved in favour of the original English report.