SIU Annual Report 2019

Contents:

Director’s Message

It is my pleasure to present the SIU Annual Report for the 2019 calendar year. Its publication is the culmination of the collective efforts of many SIU personnel, whom I thank dearly for their time and energy invested in this critical project.

It is my pleasure to present the SIU Annual Report for the 2019 calendar year. Its publication is the culmination of the collective efforts of many SIU personnel, whom I thank dearly for their time and energy invested in this critical project. The Annual Report represents a detailed look at the business of the SIU in 2019. The SIUis Ontario’s oversight agency tasked with conducting investigations of the circumstances around serious injury, allegations of sexual assault and death in cases involving the police. Staffed with civilian investigators and completely separate from the province’s police services, the SIU conducts independent investigations to determine whether there are grounds to charge a police officer in relation to the serious injury, sexual assault complaint or death under review. Where such grounds exist, the SIU director is compelled to charge the officer. Conversely, where the grounds do not exist, the SIU director cannot lay charges, and instead issues a public report summarizing the investigation and his or her reasons for decision.

The purpose giving rise to the SIU, whose creation and governing legal framework is set out in section 113 of the Police Services Act and a regulation under the Act (O. Reg. 267/10) is clear – police accountability and public confidence. Society vests incredible powers in the police, including the power to encroach on an individual’s liberty and to use force, including lethal force, in the execution of their duties. The citizenry grants these powers on condition that they will be exercised strictly in accordance with the law and that officers will be held to account for any lapses. To the extent the public trust that their police services are being held to account for their conduct, their confidence in policing grows. This is where the SIU comes in. By ensuring that police conduct is subject to rigorous and independent investigation, and that charges are laid where appropriate, the SIU ties the concern for police accountability with the need for public confidence in policing.

Ontarians may justly be proud of their SIU. Borne in 1990 of a crisis of public confidence in a system in which the police policed themselves, the SIU remains today at the forefront of civilian oversight of the police in Canada and around the world. In these pages, for example, you will read of two international delegations that visited the SIU’s offices to learn from its experience and how it operates.

I am also pleased to report that the women and men of the SIU performed admirably in meeting the challenges of 2019. Though the SIU saw a decline in its caseload year-to-year, investigative staff – investigators, forensic investigators and managers - continued to work under the pressures of a significant workload while ensuring that high standards of investigative integrity were maintained. In this, they were expertly assisted by in-house professional advice and services in the fields of victim services, training, media relations, outreach, administration, information technology, and law. I thank each of them for their tireless work.

Of course, there is always room for improvement. Thus, while the SIU has in recent years significantly reduced its backlog of cases – 151 open investigations at the end of 2019 compared to 231 at the close of 2018 – it must continue to trend in this direction if the office is to build on the trust of the community. The SIU must also do more to engage the diverse communities it serves through its outreach initiatives, including more targeted efforts in relation to young people, Indigenous and racialized communities, and other vulnerable groups within society. Finally, in line with the spirit of the 2017 report on the SIU by The Honourable Michael Tulloch, transparency remains paramount and the SIUmust continue to push the envelope with the amount of information released to the public while respecting the legal limitations in place meant to protect the integrity of SIUinvestigations.

As I write this message, I have accepted a two-year appointment as the SIU’s director, having served in the interim director capacity for most of 2019. It is a high honour and I pledge to bring my full talents and energies to bear every day while I hold the seat. The SIU belongs to the public, and we who work here are its temporary custodians. We can only hope and aspire to do you proud.

In embarking on this journey over the next couple of years, I would be remiss if I did not pay homage to the Unit’s preceding directors with whom I had the privilege to work with closely as the SIU’s counsel and then its deputy director, and from whom I learned so much – James Cornish, Ian Scott and Tony Loparco. I would especially be remiss in failing to salute Peter Tinsley, who expertly guided the SIU in a period of transformational change in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Director Tinsley passed away in April of this year. His legacy at the SIU lives on.

Sincerely,

Joseph Martino

Director, Special Investigations Unit

Making Connections to Enhance Oversight

Canadian Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement

The 2019 Canadian Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement (CACOLE) conference was held in Toronto, Ontario from May 27-30, 2019. This annual conference brings together delegates – approximately 130 this year - from police oversight agencies, community groups, law enforcement and academia from across Canada, the United States and the world. The conference – titled Experience, Challenges & Opportunities – included the following topics:- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Policing

- Excited Delirium, Conducted Energy Weapons, and Positional Asphyxia

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls – Indigenous Perspective

- Cannabis ‘A New Reality’

- Police Use of Video Technology: Limitations & Prospects

- De-Escalation and Strip Searches

- Independence

- Oversight and the Media

Meeting with Georgia’s State Inspector’s Service

On December 9, 2019, the SIU was honoured to host Sophio Jiadze, the Head of Administration of Georgia’s new State Inspector’s Service, and her associate, Adiba Hasan, a graduate student with the Munk School. Ms. Jiadze was enrolled in a fellowship program at the Munk School dealing with policing and accountability issues, and her visit to the SIU was a fact-finding mission organized through her studies to learn how the office operates. SIU staff also learned about the important work of Georgia’s new office headquartered in Tbilisi. It conducts investigations of alleged criminal activity of law enforcement officials while also serving as the country’s protectorate of people’s privacy and data.

The two offices committed to a continued relationship.

Hosting Delegation from Japan

On February 5, 2019, Mr. Satoshi Mishima, Professor of Criminal Justice in the Faculty of Law at Osaka City University, and Ms. Yoko Inoue, Attorney at Law, Kizugawa Law Office, Osaka, Japan, visited the SIU headquarters in Mississauga. They were in Canada to meet with various police oversight groups. Then SIU Director, Tony Loparco, discussed the challenges encountered by the SIU in its role of police oversight through its history from its inception in 1990.Volunteer Assignment at French Medical Institute for Mothers and Children (FMIC), Kabul, Afghanistan

From May 31, 2019 to July 31, 2019, SIU forensic investigator Aly Ramji took a leave of absence from the Special Investigations Unit and made his way to Kabul, Afghanistan, to work at the French Medical Institute for Mothers and Children (FMIC). The FMIC is a not-for-profit hospital dedicated to providing world-class medical services to children throughout Afghanistan. The hospital is run through an innovative four-way partnership between the Government of Afghanistan, the Government of France, the Aga Khan Development Network, and La Chaîne de l’Espoir, a French non-governmental organization. Mr. Ramji volunteered with the hopes of using his experience to help those less fortunate.Investigator Ramji speaks of his experience:

Approximately one year prior to my assignment, a security solutions company had gone into the FMIC to see how safety and security could be improved in all departments of the hospital. As a result, 159 recommendations were made. For instance, one recommendation outlined the need for the customer information counter to have a barrier to the public. Once arriving in Kabul, my job was to determine which recommendations had been fully implemented, which ones were in the process and which ones had not yet begun, and to provide input where necessary. For this, I relied on my experience as an SIU forensic investigator over the last several years, and as a Toronto Police Service officer for 30 years prior to that.

I was given unfettered access to every section of the hospital and staff answered my questions readily. I was also greatly assisted by members of the Safety and Security Office. At the conclusion of my assignment, I submitted my findings to the FMIC team. The report was well-received, and I was advised that the report would be presented at the annual board meeting, which was to be held shortly after my departure.

Due to turmoil and safety concerns in Kabul, including numerous incidents of explosions within the city during my time there, I was advised not to venture outside the hospital compound. Being confined to the hospital gave me the opportunity to help improve the Safety and Security Office. I was able to assist with the creation of policies and procedures, and I was able to utilize my knowledge and skills to help modernize some aspects of the Safety and Security Office. I trained security guards on certain topics, and ensured they were able to continue training others when I was back in Canada.

This assignment was an extremely fulfilling experience. The people of Afghanistan – civilians and FMIC personnel – were polite, humble and always went above and beyond to ensure I was comfortable and that my personal needs were met. At every turn, steps were taken to ensure my personal security was not compromised. I developed relationships that I am sure will last forever, and I look forward to going back to Afghanistan one day soon.

Investigator Ramji (yellow collar) providing training to security guards from the Safety and Security Office.

Investing in Education

Student Program

During the fall and winter months, the SIU engages in various cooperative student placements to give youth a chance to work in their field of study. The SIU connects with various colleges and universities to accommodate these placements during the year. In addition, the SIU has summer student work placements between April and August. Although the types of assignments given to students vary from year to year, some examples of experiences gained at the SIU include:- Data collection and various administrative functions;

- Legal research and memos;

- Assisting with the SIU case management system;

- Attending court and observing proceedings;

- Attending training and outreach sessions;

- Learning about the P.E.A.C.E. [1] model of investigative interviewing;

- Learning about investigative processes and forensic investigations;

- Participating in an investigation exercise (mock interviews, preparation of follow-up reports and the Director’s Report, etc.); and

- Observing investigations.

The SIU is proud of its student program and continues to be impressed with the caliber of students who have come through the program. While the students have learned much from the SIU, the SIU has also enjoyed the contributions and fresh perspectives offered by the students.

PROFILE: Cassidy MacKay, Summer Student

Being a Forensic and Psychology major, I was thrilled to have the chance to work as a summer student at the Special Investigations Unit in 2019. I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to apply my knowledge in such an interesting setting, while also learning new things and gaining valuable firsthand experience.

Being a Forensic and Psychology major, I was thrilled to have the chance to work as a summer student at the Special Investigations Unit in 2019. I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to apply my knowledge in such an interesting setting, while also learning new things and gaining valuable firsthand experience. In my time at the SIU, I was not only able to assist with administrative tasks, but I also learned about the investigative process. My responsibilities included receptionist and administrative duties, attending an outreach session, attending a training presentation, viewing an autopsy and completing an investigation exercise with my fellow summer students. I was able to learn about investigative procedures and methods, such as report writing and the P.E.A.C.E. interviewing technique, and apply these newfound skills to our investigation exercise. My time allowed me to gain insight into this area of law enforcement, and to consider the questions and problems that investigators must face in their investigations.

This has been an amazing experience and I am very thankful for all the staff members who supported me and included me in a variety of tasks and opportunities.

PROFILE: Lindsay Maharaj, Summer Student

My experience at the Special Investigations Unit was like no other! I had the opportunity to work alongside incredible employees and gain hands-on experience in the field of investigations and police oversight. As a Masters of Criminology and Criminal Justice Policy (CCJP) student at the University of Guelph, working at the SIU gave me several opportunities to reach my full potential, including the ability to conduct my own research and write an extensive research paper. I collected data and analyzed cases of sexual assault allegations within police services, the impact of the #metoo movement, and the role of the SIU as a civilian agency.

My experience at the Special Investigations Unit was like no other! I had the opportunity to work alongside incredible employees and gain hands-on experience in the field of investigations and police oversight. As a Masters of Criminology and Criminal Justice Policy (CCJP) student at the University of Guelph, working at the SIU gave me several opportunities to reach my full potential, including the ability to conduct my own research and write an extensive research paper. I collected data and analyzed cases of sexual assault allegations within police services, the impact of the #metoo movement, and the role of the SIU as a civilian agency. Working as a Summer Student allowed me to tag along with Investigators, attend a Coroner’s Inquest, travel for an Outreach Session with Forensic Investigators, participate in weekly meetings, initiate a mock case, integrate P.E.A.C.E. interviewing techniques, write interview synopses, and compose a Director’s Report.

I will be returning to school not only with professional learning and personal growth, but with meaningful connections within the field of justice! Thank you to all SIU staff members for making my summer experience one I will never forget and for always supporting me in my future endeavours.

Take Our Kids to Work Day

On Wednesday, November 6, 2019, the SIU participated in the Take Our Kids to Work Day. This annual event allows grade nine students to step into their future for a day and peer into the working world. This year, five students took part in the full-day program, which had them participate in an SIU “investigation” from start to finish. During the day, the students took on roles as forensic investigators and assessed, documented and collected evidence at a mock scene set up in the SIU parking lot. They also learned about forensic testing of the evidence they had collected, conducted civilian interviews and analyzed connections between the physical evidence and witness statements. The day finished with the students presenting their findings to the SIU director and learning about what the director must consider in making his final decision.

The day proved to be a great success with the students walking away with a greater appreciation of the nuts and bolts of civilian oversight in Ontario. In addition, the opportunity shed light on the potential career opportunities that exist in the justice field.

Communications

Communication with the Media

Communication with the media is important in ensuring that the SIU remains responsive, transparent and accountable to the public it serves. Because the SIU takes on cases at all hours of the day and night across the province, SIU Communications has made it a priority to respond to media 24 hours a day, seven days a week.From January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019, SIU Communications responded to approximately 600 inquiries from media via phone, email, text, Twitter and in-person. The nature of the questions varied, with media looking for the following types of information:

- Updates on SIU cases;

- Statistics; and

- Backgrounder information to get a better understanding of SIU policies and procedures.

While the vast majority of calls were from media across Ontario, SIU Communications also responded to inquiries from across the country, as well as international media.

Status of SIU Cases

The SIU is mandated with investigating incidents involving police that have resulted in serious injury, death, or an allegation of sexual assault. Due to the complexity and/or circumstances of any particular case, these investigations can require a significant amount of time to complete. The length of an investigation may be impacted by how long it takes to conduct interviews, and gather and analyze physical evidence. For example, significant delay can result when the SIU must await the completion of expert reports from outside organizations with respect to the forensic analysis of evidence or the completion of a post-mortem examination report. While the SIU recognizes it is important to resolve cases in a timely manner, the thoroughness of the investigation must take precedence over the length of time it takes to finish an investigation. In an effort to keep the public up-to-date on the progress of SIU investigations, the Unit continues to proactively provide updates on each investigation via the Unit’s Status of SIU Cases chart at https://www.siu.on.ca/en/case_status.php, a practice that began July 1, 2018.

News Releases

In 2019, the SIU issued 419 news releases.74 News releases were issued in the early stages of an investigation

The SIU has committed to issuing news releases at the beginning of investigations in cases where a death has occurred, a firearm has caused serious injury, there has been major vehicle collision, and other cases that have generated significant public interest.

227 News releases were issued in cases where the evidence did not satisfy the director

that there were reasonable grounds to lay charges

At the conclusion of an SIU investigation, if the evidence does not satisfy the director that there are reasonable grounds to lay criminal charges, a Director’s Report is produced and posted to the SIU’s website. Each time a report is published, the SIU notifies the public of the report by issuing a news release.

102 News releases were issued for cases terminated by memo

In order to promote transparency, investigations that are terminated because the mandate of the SIU is not engaged, including instances in which it is determined that no serious injury was sustained, the SIU issues a news release. This practice was initiated in the summer of 2017.

13 News releases were issued in cases where charges were laid

In 2019, charges were laid in 13 cases, and a news release was issued each time.

3 News releases were issued for non-case-related reasons (e.g. annual report, alerting the public of fraudulent calls being made using the SIU phone number, etc.)

In cases involving allegations of sexual assault, the SIU, as a general matter, will not release details to the public which could potentially identify the individual alleging a sexual assault occurred or the officer who is the subject of the allegation. This is so because the release of information related to investigations of sexual assault allegations is associated with a risk of further deterring what is already an under-reported crime and undermining the heightened privacy interests of the involved parties, most emphatically, the complainants. The SIU hopes that by not releasing identifying information in these cases, potential complainants will be encouraged to come forward. As with other types of cases, once a sexual assault investigation is underway, it is denoted on the Status of SIUCases chart.

Outreach

Presentations

Engagement with Ontario’s diverse communities and stakeholders remains at the heart of the SIU’s outreach function. A core objective of outreach is to increase public knowledge of the SIU’s mandate, while creating meaningful dialogue with community stakeholders. Developing, strengthening and fostering relationships through outreach efforts enhances transparency, encourages mutual awareness and, ultimately, increases the public’s confidence in the SIU’s work throughout Ontario.The SIU Library Series outreach initiative, begun in 2017, continued its partnership with the Toronto, London and Hamilton Public Libraries throughout 2019. Presentations were centred on five themes as they pertain to the SIU:

Program 1: What is the Special Investigations Unit - A Course for Newcomers

Program 2: Dispelling the Myths of the Special Investigations Unit

Program 3: How the Special Investigations Unit Operates

Program 4: The Science Behind Special Investigations Unit Investigations

Program 5: SIU Youth Program

While the SIU’s outreach efforts were hampered as the Outreach Coordinator position was vacant for a significant period in 2019, the following chart sets out the number of presentations made to different categories of audiences.

| Audience | Number completed |

|---|---|

| Academia (college, university, high school) | 41 |

| Community | 7 |

| Police | 6 |

| Public library series | 22 |

| TOTAL | 75 |

First Nations, Inuit and Métis Liaison Program

In 2019, the SIU investigated 19 cases where the complainant [2] identified as First Nations, Inuit or Métis.The SIU’s First Nations, Inuit and Métis Liaison Program (FNIMLP) is geared to providing culturally sensitive guidance in the Unit’s approach to incidents involving First Nations, Inuit and Métis persons or communities. In the context of cultural awareness and sensitivity, areas of focus include investigations, training, recruitment, policy development and reporting. Members of the Program also serve an outreach and liaison function by developing and maintaining positive professional relationships with leaders and representatives of First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations and communities. On a bi-annual basis, the SIU reports out to Provincial Territorial Organizations [3] with respect to the work of the FNIMLP.

Affected Persons Program

The Affected Persons Program (APP) is a vital component of the SIU, providing support services to those negatively impacted by incidents investigated by the Unit. The APP aims to respond to the psychosocial and practical needs of complainants, their family members and witnesses by offering immediate crisis support, information, guidance, advocacy and referrals to community agencies. Program staff are available to respond to the needs of affected persons 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Formally established in 2014, the Affected Persons Court Support Program continues to provide direct support services to SIU victims and witnesses throughout the court process, which can be difficult and confusing. Court support services are available to SIU victims and witnesses when an SIU investigation results in criminal charges.

The establishment and maintenance of collaborative relationships with government and community partner agencies across the province continues to be a core objective of the APP, which directly contributes to its success. These efforts continued throughout 2019, in coordination with the member agencies of the Ontario Network of Victim Service Providers, Victim Service Units, Victim Witness Assistance Programs, and the Office of the Chief Coroner. These collaborative relationships were solidified with the establishment of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with several Victim Service agencies throughout the province, including:

- Victim Services of Temiskaming & District

- Sudbury & Area Victim Services

- Victim Services of Peterborough & Northumberland

- Haldimand, Norfolk & New Credit Victim Services

- Muskoka Victim Services

- Brant County Victim Services

- Kawartha, Haliburton Victim Services

- Halton Victim Services Unit

- Victim Services Wellington

The purpose of the MOU is to clarify the roles of Victim Services and the APP when the SIU has invoked its mandate, in order to avoid service gaps/overlaps and to ensure that continuity of services is provided to SIU complainants and witnesses.

This year also saw the expansion of the APP staff complement with the addition in November of an Affected Persons Coordinator. The Coordinator brings her skills, education and experience in the field of victim services to provide practical and emotional support services to meet the unique needs of the Unit’s affected persons.

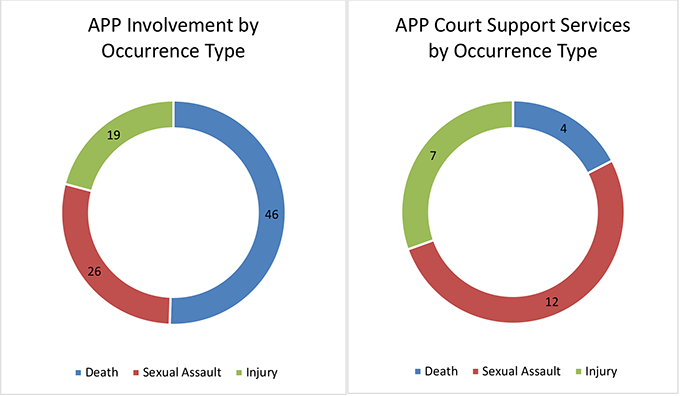

Statistics

Throughout 2019, the APP was involved in 91 cases, including 23 cases that required court support services.

Training

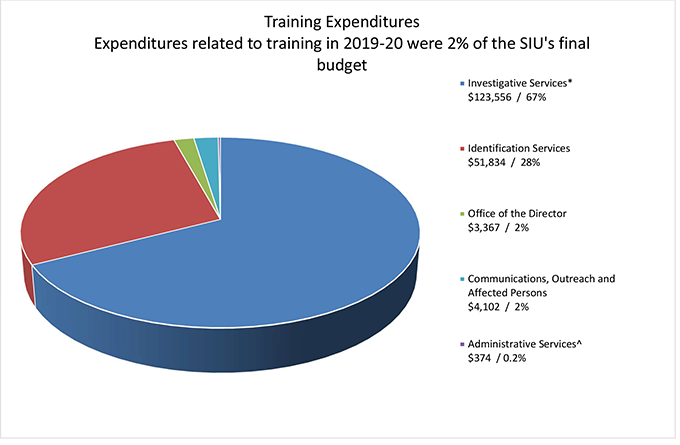

During the 2019 calendar year, SIU personnel participated in a variety of learning and development initiatives totaling approximately 2939 hours, eighty-seven percent of which was devoted to investigative and forensic training.

In keeping with past practice, the Unit continues to facilitate in-house seminars three times per year for frontline staff. These seminars included content such as peer case reviews, current trends in investigative technologies, and vicarious trauma and mental health first-aid for the SIU’s front-line staff.

SIU investigators also participated in the following external learning and development initiatives:

- The Canadian Police College (Expert Witness, Forensic Identification);

- The Ontario Police College (Criminal Investigators Training, Death Investigation, Investigative Interviewing and Sexual Assault Investigation);

- Osgoode Continuing Education Workshops (Courtroom Testimony: A Practical Skills Workshop for Police, Evidence in Criminal Investigations, 12th Annual Intensive Course on Drafting and Reviewing Search Warrants, and the 16th National Symposium on Search and Seizure Law in Canada);

- The Centre of Forensic Sciences (Biology, Firearms and Toolmarks and Toxicology Overview workshops);

- The Canadian Police Knowledge Network – (Courtroom Testimony Skills);

- The 27th Forensic Identification Seminar; and

- Attendance at both the Ontario Homicide Investigators Association and the Ontario Forensic Investigators Association yearly educational conferences.

- A Litigator’s Guide to Concurrent Criminal, Civil and Administrative Proceedings;

- Professionalism and Practice Management Issues in Administrative Law 2019; and

- The Six Minute Criminal Lawyer

To further understanding of Indigenous cultures and issues, Unit personnel participated in a number of learning and development offerings in 2019, including:

- Bimickaway Indigenous Training – Module #5; and

- Presentation by Jesse Thistle outlining the many facets of ‘homelessness’ suffered by Indigenous people, commencing with the loss of cultural identification. Mr. Thistle’s story is a powerful narrative on how the human spirit and determination can overcome a lifetime of obstacles. Mr. Thistle is Métis-Cree-Scot, from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. He is an Assistant Professor in Métis Studies at York University in Toronto, where he lives. He won a Governor General’s Academic Medal in 2016 and is a Pierre Elliot Trudeau Scholar and a Vanier Scholar. He is also the author of From the Ashes, a national bestseller.

Statiscally Speaking

Cases Opened by the SIU

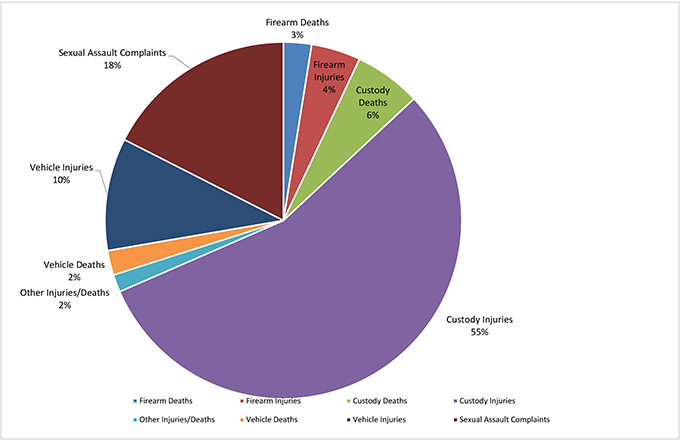

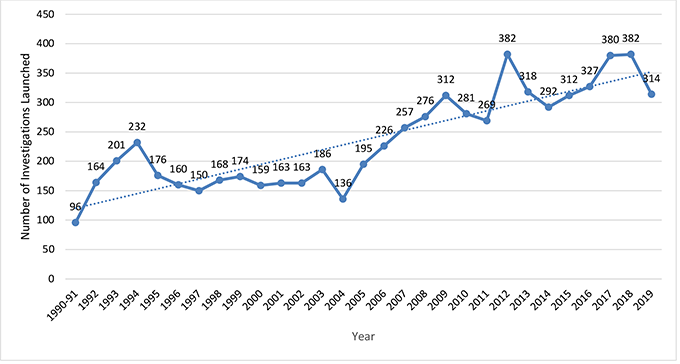

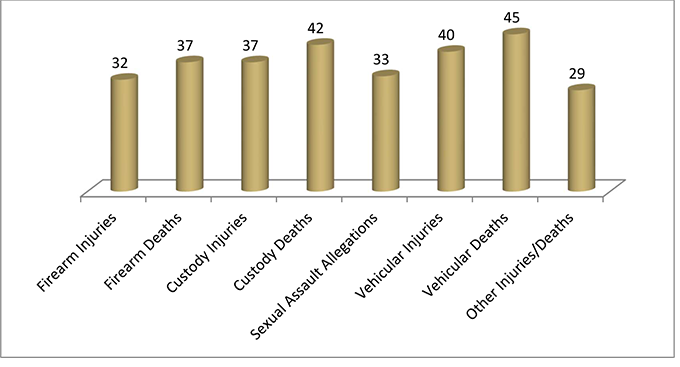

During the 2019 calendar year, 314 cases were opened by the Unit, a decrease from the 382 cases that were opened in the 2018 calendar year.| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firearm Deaths | 7 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Firearm Injuries | 8 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 14 |

| Custody Deaths | 32 | 17 | 19 | 27 | 25 | 20 | 36 | 19 |

| Custody Injuries | 229 | 194 | 169 | 188 | 197 | 229 | 202 | 174 |

|

Other Injuries/Deaths |

4 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 19 | 5 |

| Vehicle Deaths | 9 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 7 |

| Vehicle Injuries | 44 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 41 | 42 | 32 |

| Sexual Assault Complaints | 49 | 39 | 43 | 40 | 43 | 68 | 58 | 55 |

| Total | 382 | 318 | 292 | 312 | 327 | 380 | 382 | 314 |

Types of Occurrences by Percentage, 2019

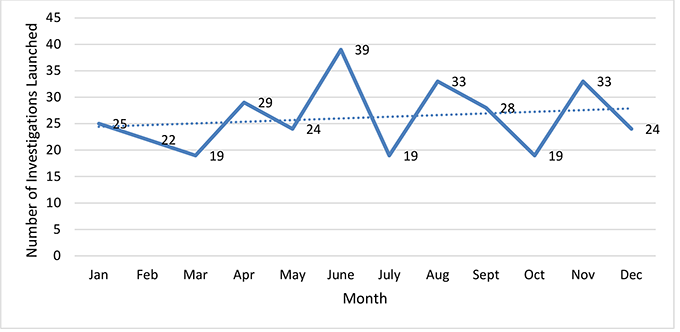

Number of Investigations Launched per Month

Total Occurrence Trend Since Inception

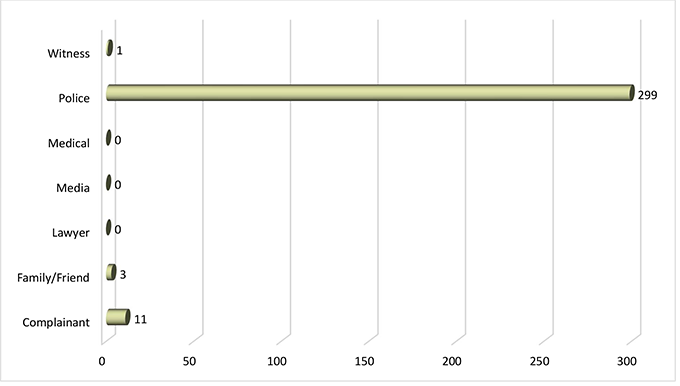

How the SIU is Notified

The majority of the time, the involved police service notifies the Special Investigations Unit. All police services in Ontario are legally obligated to immediately notify the SIU of incidents death or serious injury (including allegations of sexual assault) involving their officers. However, calls from police are not the only way the SIU can be notified. In fact, anyone can contact the Special Investigations Unit about an incident that falls within its mandate. Of the 314 investigations launched by the Unit in 2019, here is how the SIU was notified:

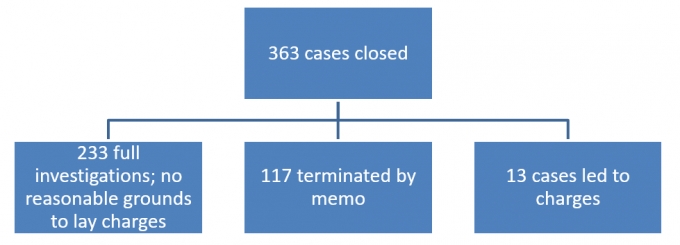

Cases Closed by the SIU

From January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019, the SIU closed 363 cases. The number of closed cases includes occurrences from the previous year that were closed in 2019 and does not include cases that remained open at the end of 2019. The average number of days to close all cases was 136.40 days. [4]

Cases Closed with No Reasonable Grounds to Lay Charges

In most cases investigated by the SIU, the director concluded that the evidence did not establish reasonable grounds to believe that there had been criminal wrongdoing on the part of the officers, and hence, no charges were laid. In 2019, 233 investigations ended in this manner.

Cases Closed by Memo

Of the 363 cases closed in 2019, 117 were closed by memo, accounting for 32% of the total number of cases. In some SIU cases, information is gathered at an early stage of the investigation which establishes that the incident, at first believed to fall within the SIU’s jurisdiction, is in fact not one that the Unit can investigate. It may be that the injury in question, upon closer scrutiny, is not in fact a “serious injury” according to the definition of serious injury that the SIU has established. In other cases, although the incident falls within the SIU’s jurisdiction, it becomes clear that there is patently nothing to investigate. Examples of such incidents include investigations in which it becomes evident early on that the injury was not directly or indirectly caused by the actions of a police officer. In these instances, the SIU director exercises his/her discretion and “terminates” all further SIU involvement, filing a memo to that effect with the Deputy Attorney General. When this occurs, the director does not render a decision as to whether a criminal charge is warranted in the case or not. These matters may, on occasion, be referred to other law enforcement agencies for investigation. Charge Cases

Criminal charges were laid by the SIU director in 13 cases, against a total of 15 officers, accounting for 3.6% of the 363 cases that were closed in 2019. These charge cases included investigations that were launched in prior years, but for which charges were laid in 2019.Information About Complainants

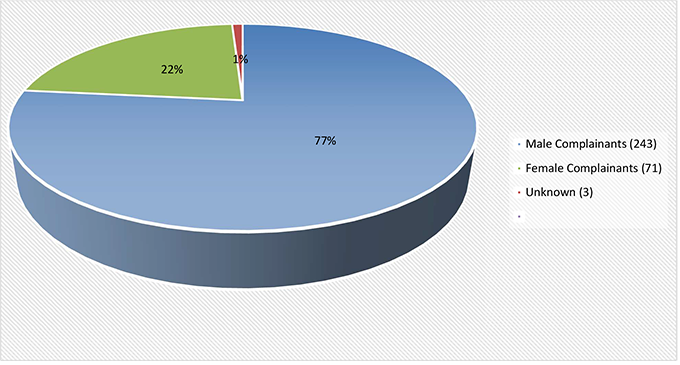

Complainants are individuals who are directly involved in an occurrence investigated by the SIU in that, as a result of interactions with police, they have died or were seriously injured, or allege that they have been sexually assaulted. There may be more than one complainant per SIU case.

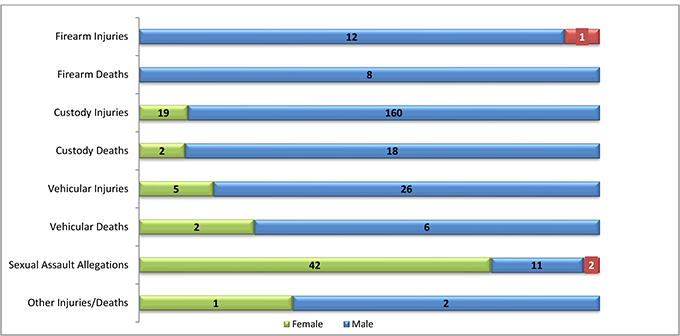

Percentage of Complainants by Gender [5]

Number of Male and Female Complainants by Case Type

Average Age of Complainant by Case Type

Investigative Response

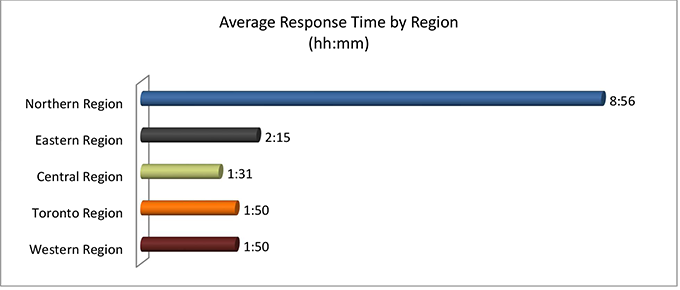

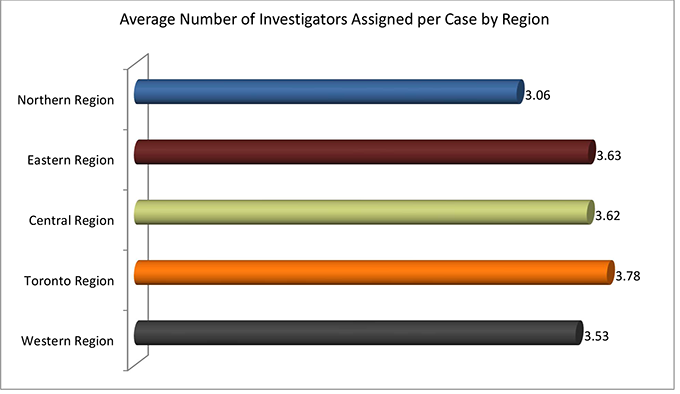

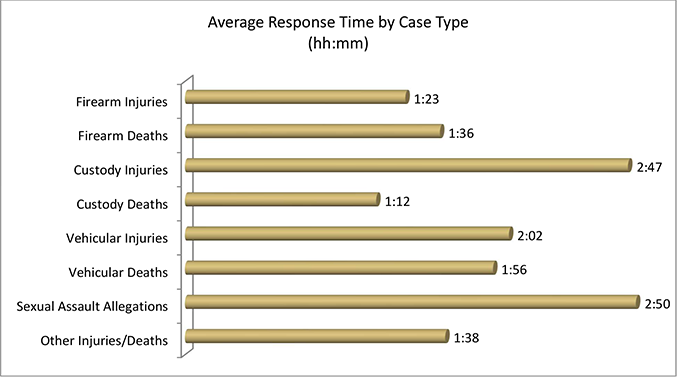

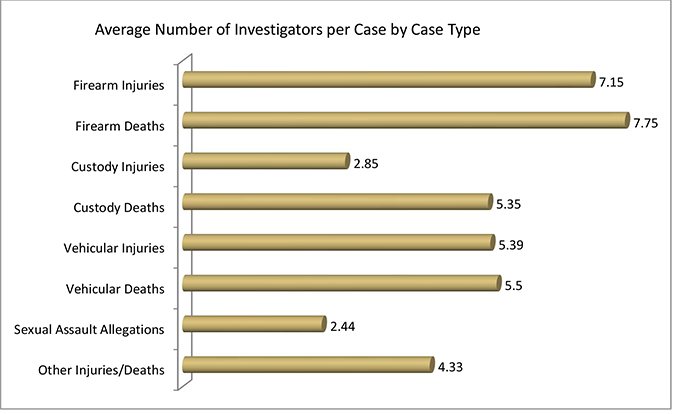

To assist in understanding the required investigative response in an SIU incident, the SIU tracks the time it takes for investigators to respond to an incident and the number of investigators deployed to a scene. Speed of response and the number of investigators initially dispatched to an incident are important in many cases because of the need to secure physical evidence and to meet with witnesses before they leave the scene.

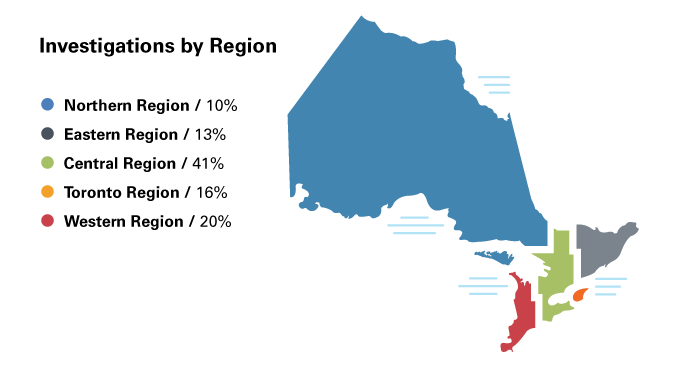

Investigations by Region

*The times calculated were for those cases that required an immediate dispatch of investigative personnel and resources. Cases in which an immediate response was determined to not be necessary were not included in this calculation.

*The times calculated were for those cases that required an immediate dispatch of investigative personnel and resources. Cases in which an immediate response was determined to not be necessary were not included in this calculation.

Cases at a Glance

The nature of the SIU’s mandate means that the Unit often deals with complex and traumatic situations involving police and civilians. Examining these situations, and arriving at a decision, is rarely easy. Under section 113(7) of the Police Services Act, the director, who cannot be a police officer or a former police officer, has the sole authority at the SIU to decide whether or not charges are warranted. The director relies on many years of experience in the area of criminal law and takes into consideration all aspects of an investigation, arriving at a decision by applying established legal principles. The director’s job is not to decide whether the police officer, who is the subject of an investigation, is innocent or guilty, but rather whether the evidence satisfies the director that there are reasonable grounds to pursue criminal charges. If a charge is laid, the courts will ultimately determine guilt or innocence by deciding whether the charge has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt.Examples of investigations carried out by the SIU in 2019 can be found below.

CHARGE: 19-PSA-027 [6]

Incident OverviewThe SIU was contacted by the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) on February 5, 2019 regarding a complaint received that same day of a sexual nature against a police officer with the Thunder Bay detachment. The alleged sexual assault of a woman reportedly occurred sometime between April of 2001 and March of 2002.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned two investigators and one forensic investigator to examine the circumstances surrounding the incident. As part of the investigation, the SIU interviewed the woman who made the allegation, two civilian witnesses and two witness officers. The subject officer declined to be interviewed and did not provide a copy of his notes to the SIU, as was the subject officer’s legal right.

Director’s Decision

Based on the evidence collected in relation to this incident, then SIU Interim Director Joseph Martino concluded that there were reasonable grounds to believe an officer with the OPP Thunder Bay detachment committed a criminal offence. As a result, on June 25, 2019, the officer was charged with one count of sexual assault, contrary to section 271 of the Criminal Code.

The case was then referred to the Justice Prosecutions Branch of the Crown Law Office—Criminal, for prosecution.

CHARGE: 19-OCI-026

Incident OverviewThe SIU was contacted by the Guelph Police Service (GPS) on February 4, 2019 regarding the arrest of a 45-year-old man that morning in Guelph.

The SIU investigation found that at approximately 3 a.m. that day, GPS officers attended a residential building on Carden Street in Guelph to conduct an investigation. Outside the main entrance of the building, a GPS officer became involved in an interaction with a man unrelated to the incident being investigated. The man was arrested and transported to the police station. He was later taken to hospital where he was diagnosed with serious injuries.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned three investigators and one forensic investigator to examine the circumstances surrounding the incident. As part of the investigation, the SIU interviewed the 45-year-old man and three witness officers. The subject officer declined to be interviewed and did not provide his notes, as was his legal right.

A canvass conducted in the area of the arrest revealed several closed-circuit camera recordings. In addition, the Unit reviewed the arrest report, dispatch reports and various policies.

Director’s Decision

Based on the evidence collected in relation to this incident, then Interim Director Joseph Martino concluded that there were reasonable grounds to believe a sergeant with the GPS committed a criminal offence. As a result, on July 3, 2019, the sergeant was charged with one count of assault causing bodily harm, contrary to section 267(b) of the Criminal Code.

The case was referred to the Justice Prosecutions Branch of the Crown Law Office—Criminal, for prosecution.

CLOSURE MEMO: 19-OCI-180

Incident OverviewIn the early afternoon of August 2, 2019, a 21-year-old man was in the custody of the Brantford Police Service (BPS) at the Brantford courthouse, awaiting his bail hearing. While lodged in a cell, the man started to repeatedly punch the concrete walls. The man was transported to hospital where he was diagnosed with a broken bone in his right hand.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned two investigators to probe the circumstances of the incident.

As part of the investigation, the 21-year-old man was interviewed.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the CCTV [7] footage from Brantford Courthouse.

Director’s Decision

Then Interim Director Joseph Martino terminated the investigation, saying, “The SIU’s preliminary inquiries included a review of the video recording of the man’s time in cells. It is patently clear that the man is solely to blame for his self-inflicted injury, and as such, the investigation is hereby discontinued, and the file closed.”

CLOSURE MEMO: 19-OCI-276

Incident OverviewIn the early morning of November 20, 2019, Peel Regional Police officers were conducting an investigation at an apartment building located at 4050 Dixie Road in Mississauga. When a 36-year-old man – a person of interest – saw the officers, he fled down a stairwell. In an effort to get away, the man attempted to leap an entire flight of stairs resulting in him landing awkwardly. He was arrested within seconds of the jump and taken to hospital for treatment of a leg injury.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned two investigators to probe the circumstances of the incident.

As part of the investigation, the 36-year-old man was interviewed, but he declined the SIUaccess to his medical file.

Director’s Decision

Then Interim Director Joseph Martino said, “While the exact nature of the man’s injury remains unknown, he having declined to release his medical records, it is clearly serious in nature given his leg was rigidly casted in the wake of the incident and surgery had been scheduled. What is clear is that the man jumped of his own volition and is the author of his own misfortune. Accordingly, the investigation is hereby discontinued, and the file closed.”

NON-CHARGE: 19-PVI-067

Incident NarrativeAt about 4 p.m. on April 3, 2019, the 63-year-old complainant, together with civilian witness (CW) #2 and CW #3, had come off Wawa Lake on their snowmobiles and were stopped north of Highway 101 looking to cross south over the roadway into town. At the same time, the subject officer (SO) was in his cruiser travelling west along Highway 101 toward Wawa in response to a reported theft at a shop in town. As the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) officer negotiated a rightward bend in the road approaching the snowmobilers’ position, he observed the complainant in his lane ahead of him and attempted to avoid a collision by swerving to the left. Moments prior, the complainant had accelerated forward onto the roadway.

The impact between the vehicles occurred in the westbound lane of Highway 101 at the roadway’s intersection with Gladstone Avenue. The front passenger side of the cruiser struck the front left side of the snowmobile, sending it west and north until it came to rest on the westbound shoulder of the highway several metres from the point of impact. The complainant was thrown from the snowmobile and landed on the roadway. The SOstopped his cruiser in the eastbound lane of the highway, exited and went to check on the complainant. The officer sustained minor injuries in the collision, apparently the result of his cruiser’s airbag deployment.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned two investigators to probe the circumstances of the incident.

In addition to examining the scene and collecting evidence, SIU investigators interviewed the complainant, two civilian witnesses and one witness officer. The SO declined to be interviewed and did not provide a copy of his notes to the SIU, as was the SO’s legal right.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials from the OPP Wawa Detachment (Superior East):

- Dispatch / Event Details report;

- Crash Data Recorder report;

- GPS data associated with the SO’s cruiser;

- Notes of a witness officer;

- OPP draft diagrams;

- Google Earth photograph of the scene;

- Preliminary photo-brief prepared for the SIU; and

- The OPP Reconstruction Report.

Director's Decision

The complainant was seriously injured on April 3, 2019 while on a snowmobile trip with a couple of friends. He was on his snowmobile attempting to cross Highway 101 in Wawa when he was struck by an OPP cruiser being operated by the SO. The complainant was transported to hospital where he was treated for multiple fractures of his left leg. On my assessment of the evidence, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the SOcommitted a criminal offence in connection with the collision.

The offence that arises for consideration is dangerous driving causing bodily harm contrary to section 320.13(2) of the Criminal Code. As an offence of penal negligence, liability under the section rests on conduct that, in addition to being objectively characterized as dangerous, amounts to a marked departure from the level of care that a reasonable person would have observed in the circumstances: R. v. Beatty, [2008] 1 SCR 49; R. v. Sharp (1984), 12 CCC (3d) 428 (Ont. C.A.). While I have no doubt that the SOwas driving dangerously in the moments before the collision, and that his dangerous driving was largely responsible for what occurred, I am of the view that the evidence falls just short of justifying criminal charges against the officer.

The central issue in the liability analysis is with the SO’s speed. While traveling west on Highway 101 some six kilometres from the scene of the collision, there was a pronounced increase in the officer’s velocity to about 136 km/h from 111 km/h eight seconds earlier, presumably in response to the theft call in Wawa. The SO continued apace westward at speeds between 121 km/h and 152 km/h over the course of the next five and a half kilometres, traveling for the most part at 140 km/h and above against a 90 km/h speed limit. Some 450 metres east of the collision site, there was a traffic sign for westbound motorists indicating a drop in the speed limit from 90 km/h to 50 km/h as the highway wound its way into the Town of Wawa. The SO appears to have entered this zone at about 138 km/h, thereafter decelerating to 113 km/h within a span of 250 metres. At the point of impact, a further 150 metres down the road, the SO was travelling at about 71 km/h.

I am satisfied that the SO’s speeds as he responded to the theft call, which were significantly in excess of the speed limits that governed the roadway over which he travelled, constituted a risk to traffic around him. I am further satisfied that the officer’s speed was the pivotal factor in the collision that occurred. The complainant appears to have done little if anything wrong in relation to the accident, and I do not believe he saw the SO’s cruiser before entering the roadway. Travelling as fast as it was, it is conceivable that the cruiser would not have been visible to the complainant until just before impact. On the other hand, the SO appears to have seen the complainant’s snowmobile entering onto the roadway but was unable to avoid a collision owing, in my view, to the speed at which he was travelling.

Further aggravating the danger caused by the SO’s speed was the officer’s failure to activate his emergency lights and/or siren. He ought to have known, particularly as he crossed into the 50 km/h zone, that traffic around him would have little time to react to his cruiser given how fast it was going. In the circumstances, the officer ought to have activated his emergency lights and/or siren to alert the public as early as possible to his presence. One is left to speculate, reasonably in my view, that the complainant might well have not ventured onto the roadway when he did had he been given advance notice of the cruiser via its siren or emergency lights.

Finally, when considering the inculpatory impact of the SO’s speed, it is important to bear in mind that a police officer’s foremost duty is at all times the preservation of life. It does a police officer no good if in responding to a call for service his or her conduct unduly endangers public safety. I fully appreciate that police officers are frequently faced with difficult choices with little time in which to make them, and that allowance must be made for less than exacting decisions made in the heat of the moment. That said, in the context of an officer who had travelled several kilometres over approximately three minutes before the collision occurred, it is difficult to countenance the persistence of the SO’s excessive speed to get to the scene of what was, after all, a property offence.

On the other side of the ledger, while one might question the wisdom of traveling as fast as the SO was to get to the scene of a reported theft, the fact remains that he was engaged in the execution of his duty and therefore exempt from the speed limits pursuant to section 128(13)(b) of the Highway Traffic Act. This is not to suggest that the SO had carte-blanche to speed as he wished without regard to public safety; however, quite apart from whether the SO paid sufficient heed to public safety as he sped westward on Highway 101, it is important to recognize that he was a police officer responding to the scene of a reported crime. In other words, if the officer’s conduct was ill-guided, it was not without rhyme or reason.

It is also true that most of Highway 101 over which the SO travelled in response to the reported theft was predominantly rural in nature with little development on either side of the road. It was only as the SO approached the Town of Wawa and the speed limit became 50 km/h for westbound traffic, some 450 metres from the collision scene, that the officer’s speed coalesced with the environment around him to create a clear and present danger of accident. In the circumstances, while I am unable to characterize the gravamen of the SO’s transgressions as fleeting or momentary, it was relatively short-lived – about half-a-kilometre and some 13 seconds.

The evidence further suggests that snowbanks on the shoulder of the highway, trees and shrubs on both sides of the snowmobile trail, and a “no parking” sign just east of the location where the complainant attempted to cross the roadway may have obstructed his line of sight toward the approaching cruiser, thereby contributing to the accident. In fact, the obstructions may well have detracted from the SO’s sightlines as well. All of which is to suggest that the officer’s speed was likely not the only factor at play in the collision.

Lastly, it would not appear that the environmental conditions that prevailed at the time exacerbated the risks to public safety inherent in the SO’s speed. The roadway was dry and in fair condition, and visibility was good.

In the final analysis, while one may legitimately criticize the SO for the manner in which he operated his police cruiser in the moments leading to its collision with the complainant and his snowmobile, I am unable to reasonably conclude that the officer’s conduct was so substandard as to amount to a marked deviation from a reasonable level of care. Accordingly, there are no grounds for proceeding with charges in this case and the file is therefore closed.

The Director’s Decision found here has been condensed from its original version. The full analysis, along with details on the evidence collected and relevant legislation, can be found at https://www.siu.on.ca/en/directors_report_details.php?drid=634.

NON-CHARGE: 19-TCI-139

Incident NarrativeShortly before 10 p.m. on June 18, 2019, the Toronto Police Service (TPS) received a call from the resident of a house on Torrens Avenue (CW). The CW indicated that a male (complainant) had forced his way into the residence and was currently barricaded in a bedroom in the possession of a knife or fork, which he had used to threaten him. According to the CW, the complainant appeared intoxicated and was very angry. Police officers were dispatched to the address.

Officers began arriving at the scene at about 10:10 p.m. A number of them entered the house but quickly exited when, from behind the closed bedroom door, the 36-year-old complainant was heard to threaten them with death. The house was contained from the outside pending the arrival of the Emergency Task Force (ETF).

At approximately 10:30 p.m., a team of ETF officers entered the home and convened outside the barricaded bedroom door. The subject officer (SO), a member of the team, took the lead in attempting to communicate with the complainant through the door. The complainant shouted, moaned and banged around. His responses to the officers were largely unintelligible. Concerned for the complainant’s well-being, the ETF officers forced the bedroom door open and stepped inside. The complainant was quickly located on the floor next to the bed. The officers had no difficulty in securing the complainant in handcuffs, whereupon he was removed from the bedroom and placed on a stretcher in the kitchen.

Following his arrest, the complainant was taken to hospital where he was treated for stab wounds and a collapsed lung.

Forensic examination of the bedroom revealed the presence of five knives and a barbeque fork.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned four investigators and one forensic investigator to probe the circumstances of the incident.

In addition to examining the scene and collecting evidence, SIU investigators interviewed the complainant and one civilian witness. Three witness officers were interviewed, and the notes from seven other police officers were received and reviewed. The SO participated in an SIU interview and provided a copy of his notes.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials from the TPS:

- Charge List-the complainant;

- General Occurrence report;

- Dispatch / Event Details reports (x4);

- Communication recordings;

- Injury Report (Police)-the complainant;

- Motor Vehicle Accident Report;

- Notes of the SO and witness officers;

- TPS Procedure-Arrest;

- TPS Procedure-ETF; and

- TPS Procedure-Use of Force.

Director's Decision

The complainant suffered a collapsed lung and stab wounds on June 18, 2019 shortly before he was arrested by TPS officers. Among the arresting officers was the SO. On my assessment of the evidence, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the SOcommitted a criminal offence in connection with the complainant’s arrest and injuries.

Pursuant to section 25(1) of the Criminal Code, police officers are protected from criminal liability for force used in the course of their duties provided such force was reasonably necessary in the execution of an act that they were authorized or required to do by law. The officers who responded to the home on Torrens Avenue were engaged in the lawful exercise of their duties. The complainant had forcibly entered the home, armed himself with an edged weapon and barricaded himself in a bedroom. He was clearly subject to lawful arrest. Once inside the home, the team of ETF officers attempted to communicate with the complainant but quickly discerned that the complainant was not of sound mind and incapable of responding rationally. Knowing that he had a knife or fork with him, and concerned for his safety, the officers forced the bedroom door open and quickly took the complainant into custody. Aside from taking hold of the complainant to secure him in handcuffs, little if any force was used in his arrest. In the result, it is apparent the officers did not use excessive force in effecting the complainant’s lawful arrest.

I am further satisfied that there is no viable suggestion of liability on the part of the officers rooted in criminal negligence. The complainant’s health was as much a concern motivating the officers’ conduct as was the need to apprehend an alleged offender. To reiterate, the SO and his colleagues acted quickly to apprehend the complainant; 10 to 15 minutes had elapsed between the moment the ETF officers entered the home and their entry into the bedroom – a relatively short period of time given information at the officers’ disposal of a weapon in the complainant’s possession and the need to exercise some caution in the circumstances. Tactical paramedics were at the ready and able to assess the complainant promptly following his arrest, at which time the complainant’s wounds were noted and he was taken to hospital. On this record, I am satisfied the ETF officers acted with due care and regard for the complainant’s well-being.

In the final analysis, there are no reasonable grounds to conclude that the officers are criminally responsible by way of unlawful force or a want of care for what appear to have been the complainant’s self-inflicted injuries. Accordingly, there is no basis for proceeding with charges in this case and the file is closed.

The Director’s Decision found here has been condensed from its original version. The full analysis, along with details on the evidence collected and relevant legislation, can be found at https://www.siu.on.ca/en/directors_report_details.php?drid=654.

NON-CHARGE: 19-OFI-074

Incident NarrativeOn April 10, 2019, the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) contacted the Greater Sudbury Police Service (GSPS) to seek their assistance. They were tracking a white pickup truck heading north toward the Sudbury area. Its occupants, the 22-year-old complainant and his passenger, civilian witness (CW) #1, were wanted in connection with a recent armed robbery and firearms offences. The GSPS were cautioned that the complainant was suspected of having a shotgun in his possession and was known to have fled from attempted police stops in the past, striking police vehicles in the process.

The GSPS tactical team was mobilized and met at the police station to discuss the situation and plan their intervention. Officers in unmarked tactical trucks would deploy ahead of the suspects’ path of travel and intercede to take them into custody after they had come to a stop.

At about 10:45 p.m., the tactical team received word from the OPP, whose officers were still tailing the complainant and CW #1, that they were traveling north on Long Lake Road in Sudbury toward the Four Corners intersection. The tactical officers convened in the area. Witness officer (WO) #4, WO #12 and WO #13 were together in a tactical truck, and WO #1, WO #2 and the SO in another. They followed the pickup truck as it turned into Plaza 69 on the northwest corner of the intersection before exiting to cross Regent Street into the Esso gas station.

As the pickup truck parked with its front pointed toward a propane gas tank display cabinet against the wall of the gas station shop, the decision was made to box it in with the use of the tactical vehicles. Arriving first on scene some 30 seconds after the pickup truck came to a stop, WO #12 drove to within a metre of the vehicle’s rear. Seconds later, trucks driven by WO #1 and WO #11 came to a stop with their front ends adjacent to the pickup on its passenger and driver sides, respectively. The officers exited their vehicles with guns drawn, surrounded the pickup truck and ordered its occupants to show their hands.

Realizing that he had been cornered by the police, the complainant started his engine and accelerated rearward directly into the front of WO #12’s vehicle. The force of the impact sent the tactical vehicle backward a short distance. The complainant continued to accelerate backward against the tactical truck, spinning his wheels, but failed to create any further space between the vehicles. Some 15 seconds after the initial collision, the complainant accelerated forward and crashed into the propane gas tank display. Immediately thereafter, an SUV, with the OPP officers who had followed the suspects into Sudbury and onto the gas station, used its front end to push the rear passenger side of the pickup truck about a metre or more. Seconds after that, the SO opened the driver’s door whereupon the complainant emerged from the pickup truck and went to the ground. The complainant was subsequently handcuffed by WO #12 and taken to hospital having sustained bullet wounds to his left arm and leg. CW #1 was also removed from the pickup truck and arrested.

The SO was the only officer who discharged his firearm – a C8 rifle. The weight of the evidence, including a count of the rounds contained in his firearm after the shooting (25), information about the customary number of rounds loaded by tactical team officers in their C8 rifles (28) and the number of spent cartridge cases found at the scene (3), indicates that the SO fired his weapon three times. While the evidence regarding the officer’s position at the time the shots were fired is imprecise, it suggests the SO was standing in front of the pickup truck when he first fired and had travelled to the driver side of the vehicle near the driver’s door when the second two rounds were let off in quick succession.

The Investigation

The SIU assigned five investigators and three forensic investigators to probe the circumstances of the incident.

The SIU interviewed two civilian witnesses, but not the complainant as he declined to be interviewed and did not consent to the release of his medical records. Eleven witness officers were interviewed, and the notes from an additional 26 police officers were received and reviewed. The SO declined to be interviewed and did not provide his notes, as was the subject officer’s legal right.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials from the GSPS and OPP Sudbury Detachment:

- Arrest Report-the complainant;

- Arrest Report-CW #1;

- Communications recordings;

- Dispatch report;

- Crash Data Retrieval data;

- Crown Brief;

- Daily Arrest Record;

- Event Details report;

- Field Sketch;

- GSPS Witness List;

- GSPS Internal Memo regarding SIU investigation;

- GSPS Involved Officer List;

- GSPS note regarding ESSO station's staff;

- GSPS Officer Schedule;

- GSPS scene video;

- GSPS Total Station data;

- Information for Bail Hearing-the complainant;

- Notes of all witness officers and 24 undesignated officers;

- Occurrence Report;

- Involved Officers;

- OPP aerial video;

- Probation Order – CW #1 (x2)

- Procedure-Use of Force;

- Procedure-Arrest;

- Scene Registry;

- Team Use of Force Report;

- Training Record-Defence Tactics-the SO; and

- Training Record-Firearms Qualifications-the SO.

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following records from the Sudbury Emergency Medical Services and the Health Sciences North:

- Ambulance Call Report (x2); and

- Medical records for CW #1.

Upon request, the SIU obtained CCTV video collected from the ESSO gas station.

Director's Decision

In the evening of April 10, 2019, the complainant was in a pickup truck with his girlfriend parked at an Esso gas station on Regent Street in Sudbury when his vehicle was suddenly surrounded by the police. Officers with the GSPS had followed the truck to the location intending to arrest its occupants. Within seconds of the officers’ arrival, the complainant was shot and wounded by gunfire discharged by the SO – the subject officer in the SIUinvestigation that ensued. On my assessment of the evidence, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the SO committed a criminal offence in connection with the shooting.

Whether considered pursuant to section 25(3) of the Criminal Code, setting out the limits of permissible force used by police officers that is intended or likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm, or section 34, prescribing the boundaries of justifiable force in the defence of oneself or another from an actual or threatened attack, I am satisfied on reasonable grounds that the SO acted lawfully when he discharged his firearm and caused injury to the complainant. The former provides police officers with immunity from criminal liability provided the force in question was reasonably necessary in aid of an act that they were required or authorized to do by law and they acted under a reasonable apprehension that said force was necessary to meet a threat of death or grievous bodily harm to oneself or another. The latter requires that the defensive act be reasonable with reference to the relevant circumstances, including the nature of the force or threat, whether there were other means to protect oneself or another, and whether any party to the incident used or threatened to use a weapon.

As was his legal right, the SO declined to be interviewed by the SIU or authorize the release of his notes. The SIU is therefore without first-hand information regarding the officer’s state of mind at the time he fired his rifle. That said, I accept that the SO feared for his life when he discharged his weapon based on the circumstantial evidence and an utterance he made to a fellow officer in the wake of the incident.

A GSPS officer was among the tactical officers deployed that night. He, together with two team members, arrived at the Esso station in their vehicle moments after the shooting had occurred. In an exchange with the SO, says the GSPS officer, the officer told him he was scared he was going to be run over by the pickup truck and believed he had to stop the complainant. I have no reason to doubt the reliability of the GSPS officer’s evidence. Nor do I doubt that the SO’s statements accurately reflect how he felt at the time of the shooting. While potentially self-serving, those statements attract a level of authenticity for their relative contemporaneity with the events in question. Their reliability is further bolstered by the perceptions of similarly situated officers present at the time. For example, several officers in and around the pickup truck when the shooting happened believed the complainant represented a real and present risk to their lives and safety should he manage to free his vehicle from the police blockade. Specifically, they feared that the complainant would strike an officer with the pickup truck, particularly those situated on the driver side of the vehicle which was his most likely escape route. To reiterate, the SO was positioned on the driver side of the pickup truck in close proximity to the vehicle.

The analysis turns to the reasonableness of the SO’s apprehensions and the action he took. The officer was positioned in front of the pickup truck when he first shot at the complainant through its windshield. The complainant was in the process of accelerating rearward into the tactical truck behind him at the time. That action would have given the officers the impression, and did in fact so impress the witness officers who spoke with the SIU, that the complainant was bent on escaping police custody by ramming his truck free of the police vehicles. While one might question the wisdom of taking up such a vulnerable position, the fact remains that the SO was completely exposed to an immediate and potentially lethal risk in the event the complainant decided to accelerate forward. The shot did not incapacitate the complainant and, as it turns out, he did in fact travel forward mere seconds after the SO’s initial discharge, smashing into the propane gas tank display cabinet with significant force. Fortunately, the SO had re-positioned himself beside the driver side of the truck by that point. In the circumstances, I have no difficulty in concluding that the SO’s beliefs and corresponding action in relation to the first discharge were reasonable.

More difficult is the question of reasonableness in connection with the second two shots discharged by the SO. These were fired at close range into the driver’s seat compartment of the pickup truck some 16 seconds after the first shot. At that time, the SO was not in front of the pickup truck; he was standing along the driver side within a metre or so of the driver’s door. Arguably, he was no longer in any imminent peril by the movement of the truck. In the circumstances, was a resort to lethal force and the SO’s belief in its necessity reasonable? I believe they were.

The law countenances an officer’s mistaken belief in the necessity of force of one kind or another so long as the belief was reasonably held. That is, might a reasonable person in the officer’s shoes have been similarly mistaken? Moreover, the law does not require that officers caught up in volatile and dangerous situations measure their responsive force with precision; what is required is a reasonable response, not an exacting one: R. v. Nasogaluak[2010] 1 SCR 206; R. v. Baxter (1975), 27 CCC (2d) 96 (Ont. CA). Consider the SO’s situation. He would have been briefed that the complainant was considered armed and dangerous. He was wanted for armed robbery, suspected of having a shotgun in his possession and known for forcing police vehicles out of the way during attempted stops. As the SO left his tactical truck and moved toward the pickup truck, it would have become immediately clear that the complainant had no intention of surrendering peacefully. He had rammed the police vehicle behind him around the time the SO initially discharged his weapon and continued to operate the pickup truck following the first shot despite armed police officers ordering him to stop at gunpoint. In fact, it appears the pickup was accelerating forward when the SO let off two additional rounds in quick succession into the driver’s door window just before it smashed into the propane gas tank display.

Was retreat an option? Perhaps, but I am unable to find fault with the SO’s decision to not give way as the complainant attempted to maneuver out of the police barricade. The complainant had in recent days engaged in a course of violent and reckless behaviour that threatened the lives and safety of the public around him. His conduct on the day in question when faced with an overwhelming show of force by the police was no different. Indeed, I am persuaded that the complainant would not have willingly desisted but for the SO’s intervention. I am further persuaded that the complainant would have remained a grave risk to public safety had he managed to escape. On this record, the officers, including the SO, were within their rights in seeking to effect the complainant’s arrest as soon as possible and to stand their ground in doing so.

There is also the matter of the sawed-off shotgun that was recovered from the pickup truck following the shooting. To be clear, there is no indication in the evidence that the complainant ever wielded the firearm during the incident. None of the police witnesses questioned by the SIU mentioned seeing a gun in the complainant’s possession and the SOsaid nothing of a firearm when explaining to a GSPS officer why he did what he did. Nevertheless, most if not all of the witness officers who were present at the time alluded to the likely presence of a shotgun in the pickup truck in describing the danger they were facing. The shotgun’s presence in the pickup truck gives credence to the officers’ concerns. I am satisfied that the same concerns would have weighed on the SO’s mind to some degree as he approached the truck.

While it may be in the cold light of hindsight that the SO’s life was not in any immediate danger when he fired his second and third rounds, the officer’s belief to the contrary and his corresponding firearm discharges were in my view reasonable nonetheless. On the aforementioned record, confronted with a violent and armed individual determined to escape police apprehension and seemingly without any qualms about using his pickup truck to effect his purpose, the SO had good cause in the heat of the moment to believe that the truck’s continued operation represented a threat to life and limb necessitating the use of lethal force to disable its driver.

For the foregoing reasons, I am unable to reasonably conclude that the shooting was anything other than lawful force in aid of the complainant’s arrest pursuant to section 25(3) and/or section 34 of the Criminal Code. Consequently, there is no basis to proceed with charges in this case and the file is closed.

The Director’s Decision found here has been condensed from its original version. The full analysis, along with details on the evidence collected and relevant legislation, can be found at https://www.siu.on.ca/en/directors_report_details.php?drid=676#fn

Case Breakdown Chart

| County | Population* | Police Service | Total Cases | % of Total | Firearm Injuries | Firearm Deaths | Custody Injuries | Custody Deaths | Vehicle Injuries | Vehicle Deaths | Sexual Assault Allegations | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parry Sound | 42,824 | OPP Almaguin Highlands Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Muskoka† | 60,599 | OPP Bracebridge Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| OPP Huntsville Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Sudbury | 21,546 | OPP Espanola Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Timiskaming | 32,251 | OPP Temiskaming Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Kenora† | 65,533 | OPP Dryden Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| OPP Kenora Detachment | 4 | 1.3% | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| OPP Red Lake Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| OPP Sioux Lookout Detachment | 3 | 1.0% | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Nipissing† | 83,150 | North Bay Police Service | 4 | 1.3% | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| Cochrane† | 79,682 | OPP South Porcupine Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Algoma† | 114,094 | OPP Superior East (Wawa) | 2 | 0.7% | 2 | |||||||

| OPP Superior East (White River) | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Thunder Bay† | 146,048 | Thunder Bay Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| OPP Armstrong Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| OPP North West Region Headquarters | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| OPP Thunder Bay Detachment | 2 | 0.7% | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Greater Sudbury | 161,647 | Greater Sudbury Police Service | 5 | 1.6% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| TOTALS | 840,739* | % of Population: 6.3% | 32 | 10.5%† | 1 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 3 |

| County | Population* | Police Service | Total Cases | % of Total | Firearm Injuries | Firearm Deaths | Custody Injuries | Custody Deaths | Vehicle Injuries | Vehicle Deaths | Sexual Assault Allegations | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lennox and Addington | 42,888 | OPP Napanee Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Lanark | 68,698 | OPP East Region Headquarters | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Prescott and Russell | 89,333 | OPP Hawkesbury | 2 | 0.6% | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Leeds and Grenville | 100,546 | Brockville Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Gananoque Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| OPP Prescott Detachment (Grenville County) | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry† | 113,429 | Cornwall Community Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| OPP Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Hastings† | 136,445 | Belleville Police Service | 2 | 0.6% | 2 | |||||||

| Frontenac | 150,475 | Kingston Police Service | 8 | 2.5% | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Ottawa | 934,243 | Ottawa Police Service | 15 | 4.7% | 1 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| OPP Upper Ottawa Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Kawartha Lakes | 75,423 | City of Kawartha Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Northumberland | 85,598 | Cobourg Police Service | 2 | 0.6% | 1 |

1 |

||||||

| Renfrew | 102,394 | OPP Pembroke Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Peterborough | 138,236 | Peterborough-Lakefield Community Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| TOTALS | 2,080,505* | % of Population: 15.5% | 40 | 12.7%† | 0 | 4 | 19 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| County | Population* | Police Service | Total Cases | % of Total | Firearm Injuries | Firearm Deaths | Custody Injuries | Custody Deaths | Vehicle Injuries | Vehicle Deaths | Sexual Assault Allegations | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dufferin | 61,735 | Orangeville Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Haldimand-Norfolk | 109,787 | OPP Haldimand County Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| OPP Norfolk County Detachment | 3 | 1.0% | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| Brant† | 134,808 | Brantford Police Service | 12 | 3.9% | 1 | 9 | 2 | |||||

| Simcoe | 479,650 | Barrie Police Service | 4 | 1.3% | 4 | |||||||

| OPP Collingwood Detachment | 3 | 1.0% | 3 | |||||||||

| OPP Huronia West Detachment | 3 | 1.0% | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| OPP Nottawasaga Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| OPP Southern Georgian Bay Detachment | 2 | 0.7% | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| OPP Orillia Detachment | 3 | 1.0% | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Niagara | 447,888 | Niagara Regional Police Service | 15 | 4.9% | 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| OPP Niagara Detachment | 3 | 1.0% | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| Hamilton | 536,917 | Hamilton Police Service | 16 | 5.2% | 10 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Durham | 645,862 | Durham Regional Police Service | 9 | 3.0% | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| York | 1,109,909 | York Regional Police Service | 17 | 5.6% | 2 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Peel | 1,381,739 | Peel Regional Police Service | 36 | 11.8% | 4 | 21 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |||

| OPP Caledon Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| TOTALS | 5,456,730* | % of Population: 39.9% | 130 | 42.6%† | 7 | 1 | 79 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 21 | 1 |

| County | Population* | Police Service | Total Cases | % of Total | Firearm Injuries | Firearm Deaths | Custody Injuries | Custody Deaths | Vehicle Injuries | Vehicle Deaths | Sexual Assault Allegations | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huron | 59,297 | OPP Huron Detachment | 2 | 0.7% | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Bruce | 68,147 | Hanover Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Elgin | 88,978 | OPP Elgin County Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| St. Thomas Police Service | 3 | 1.0% | 3 | |||||||||

| Grey | 93,830 | OPP Grey County Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Oxford | 110,862 | Woodstock Police Service | 2 | 0.7% | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Chatham-Kent | 102,042 | Chatham-Kent Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| Lambton | 126,638 | Sarnia Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||

| OPP Lambton Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Wellington | 222,726 | Guelph Police Service | 3 | 1.0% | 3 | |||||||

| North Wellington Operations Centre (Teviotdale) Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Essex | 398,953 | Windsor Police Service | 14 | 4.6% | 11 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| OPP Essex Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| OPP Essex County Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| OPP Leamington Detachment | 2 | 0.7% | 2 | |||||||||

| Middlesex† | 455,526 | London Police Service | 11 |

3.5% |

10 | 1 | ||||||

| OPP London Detachment | 2 | 0.6% | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| OPP Middlesex Detachment | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| OPP Western Region Headquarters | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Strathroy-Caradoc Police Service | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | |||||||||

| Waterloo | 535,154 | Waterloo Regional Police Service | 11 | 3.5% | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |||

| TOTALS | 2,338,949* | % of Population: 17.4% | 62 | 19.6%† | 0 | 2 | 40 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| County | Population* | Police Service | Total Cases | % of Total | Firearm Injuries | Firearm Deaths | Custody Injuries | Custody Deaths | Vehicle Injuries | Vehicle Deaths | Sexual Assault Allegations | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 2,731,571 | Toronto Police Service | 48 | 15.2% | 4 | 1 | 26 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 9 | |

| OPP Toronto Detachment | 4 | 1.3% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| TOTALS | 2,731,571* | % of Population: 20.3% | 52 | 16.5% | 5 | 1 | 27 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 0 |

* Population information provided by 2016 Census Canada. Statistics Canada excludes First Nations data where enumeration was incomplete. For further information, please refer to the Statistics Canada website. The total population for each region includes a population figure for counties in which no SIU cases took place, and therefore are not listed on the chart.

† Inconsistencies in total percentages are due to rounding.