SIU Director’s Report - Case # 16-OVI-318

Warning:

This page contains graphic content that can shock, offend and upset.

Contents:

Mandate of the SIU

The Special Investigations Unit is a civilian law enforcement agency that investigates incidents involving police officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The Unit's jurisdiction covers more than 50 municipal, regional and provincial police services across Ontario.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Information restrictions

Freedom of Information and Protection of Personal Privacy Act ("FIPPA")

Pursuant to section 14 of FIPPA (i.e., law enforcement), certain information may not be included in this report. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- Confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by law enforcement agencies; and

- Information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding.

Pursuant to section 21 of FIPPA (i.e., personal privacy), protected personal information is not included in this document. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- subject officer name(s)

- witness officer name(s)

- civilian witness name(s)

- location information

- witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence and

- other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation

Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 ("PHIPA")

Pursuant to PHIPA, any information related to the personal health of identifiable individuals is not included.

Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from this report because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner's inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.

Mandate engaged

The Unit's investigative jurisdiction is limited to those incidents where there is a serious injury (including sexual assault allegations) or death in cases involving the police.

"Serious injuries" shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. "Serious Injury" shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU's investigation into the serious injury sustained by a 44-year-old woman in a motor vehicle collision on December 17, 2016.

The investigation

Notification of the SIU

The SIU was notified of the incident on December 17, 2016, at 2:25 p.m. by the Hamilton Police Service (HPS).

HPS reported that on December 17, 2016, at 2:00 p.m., the Subject Officer (SO) saw a black Volvo driving west on Rymal Road East at Upper Centennial Avenue. The SO checked the licence plate of the vehicle and found it had been reported missing. The SO activated his cruiser's emergency lights, but the vehicle sped off westbound on Rymal Road East.

The SO disengaged and turned off his emergency lights. The vehicle continued at a high rate of speed and collided with another vehicle at Rymal Road East and Terryberry Road/Whitedeer Road[1]. The driver of the vehicle [now known to be Civilian Witness (CW) #1] got out and commandeered another vehicle and drove off westbound on Rymal Road. The passenger of the black Volvo, CW #2, was placed into custody.

The Complainant, who was driving the second vehicle, was taken to the hospital with a shoulder injury.

The Team

Number of SIU Investigators assigned: 4

Number of SIU Forensic Investigators assigned: 2

SIU Forensic Investigators responded to the scene and identified and preserved evidence. They documented the relevant scenes associated with the incident by way of notes, photography, videography, sketches and measurements.

Complainant:

44-year-old female interviewed, medical records obtained and reviewed

Civilian Witnesses

CW #1 Not interviewed[2]

CW #2 Interviewed

CW #3 Interviewed

CW #4 Not interviewed[3]

CW #5 Not interviewed

Witness Officers

WO #1 Interviewed

WO #2 Not interviewed, but notes received and reviewed[4]

Subject Officers

SO Declined interview, as is the subject officer's legal right. Prepared statement received and reviewed.

Incident narrative

Shortly after noon on December 17, 2016, the SO was operating a fully marked police cruiser on Upper Centennial Parkway when he observed a black Volvo, being driven by CW #1. The SO queried the Volvo's licence plate and it came back as missing.

The SO activated his emergency lights to stop the Volvo, but CW #1 immediately increased his speed and turned into the middle turning lane to pass several vehicles. Because of the dangerously high speed of the Volvo, the SO discontinued his attempt to stop the vehicle and shut off his emergency lights, but continued to follow it.

CW #1 then drove through the intersection of Rymal Road East and Terryberry/Whitedeer Road against a red light and struck the Complainant's Chevrolet. The Complainant's vehicle then struck a traffic light pole that was on the median, knocking it down. CW #1 exited the Volvo and ran from the scene. CW #1 then assaulted CW #3 and took his vehicle, and drove off. CW #1 was located and arrested several weeks later.

The Complainant was transported to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with a non-displaced fracture to her left scapula.

Evidence

The Scene

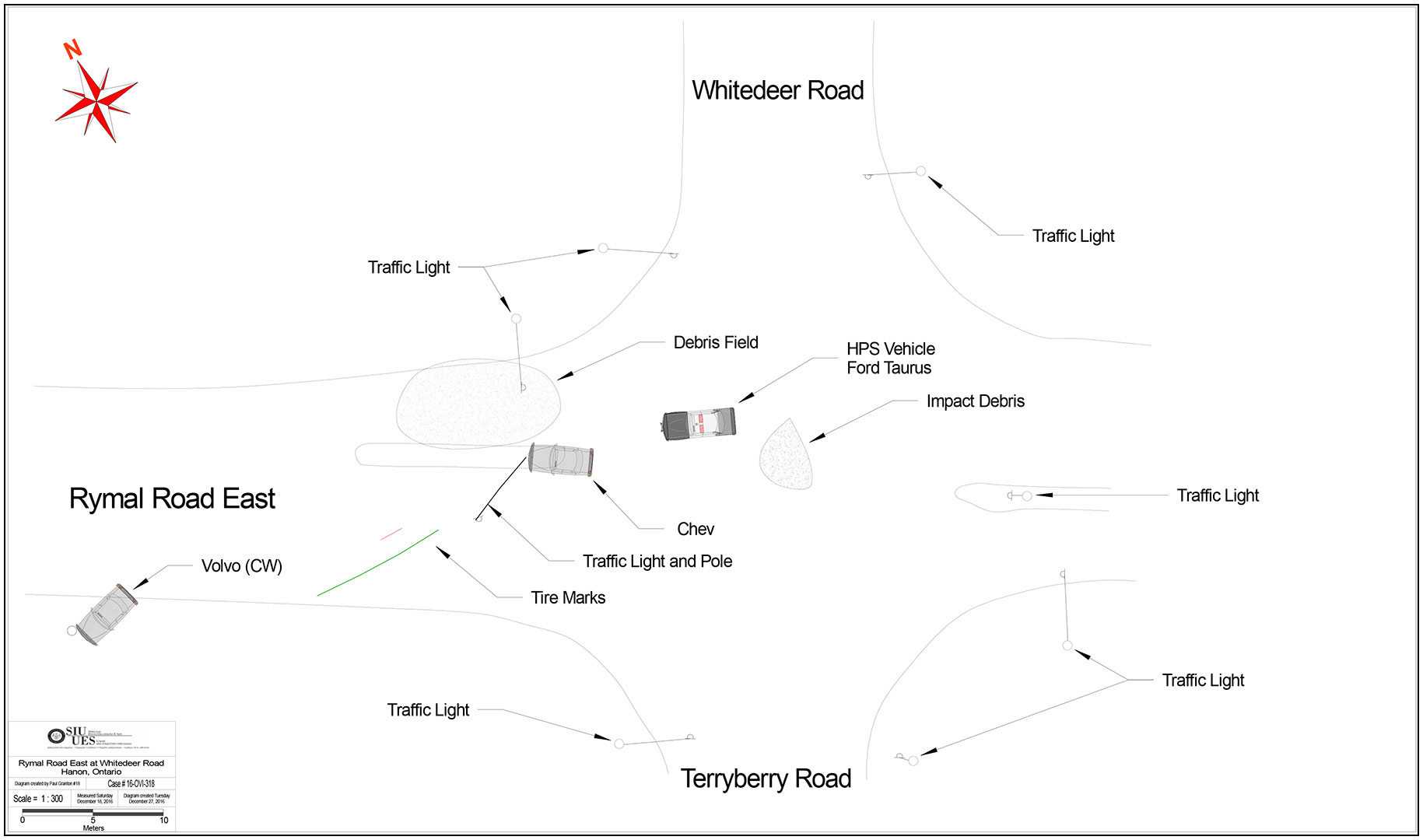

- Rymal Road is aligned in a eastbound and westbound direction. It was a one lane road from Upper Centennial Parkway. The speed limit was 60 km/h

- Terryberry Road was a short distance road that was on the south side of Rymal Road. It was a drive through road, with a dead end, that leads into a shopping area. Whitedeer Road was on the north side of Rymal Road and it lead into a residential area

- The SO's cruiser, a Ford Taurus, was located on the westbound lane of Rymal Road and Whitedeer Road and it was facing west. There was no visible damage to the cruiser

- The Complainant's vehicle, which was a black coloured Chevrolet, was located on a raised island on Rymal Road at the intersection of Rymal Road and Terryberry/Whitedeer Road. There was heavy front left and front end damage. The driver side airbag was deployed. The vehicle had collided with a traffic light pole that was on the median and it was knocked down

- The vehicle that CW #1 was driving, which was a black coloured Volvo, was located facing southwest on the south side of Rymal Road. The front end of the Volvo was in contact with a wooden hydro pole. There was heavy front end and right side damage. There were tire marks that travelled in a southwest direction just prior to the snow mounded curb where the vehicle had come to rest. They were related to and consistent with where the Volvo came to a stop

- The distance from Upper Centennial Parkway and Rymal Road to Rymal Road and Terryberry/Whitedeer Road was 1.1 km, and

- There was no evidence to suggest that the Volvo and the SO's cruiser had made any contact

Scene Diagram

Physical Evidence

The SO's Vehicle Automatic Vehicle Location/Global Positioning System (GPS) Data Summary

- At 12:48:38 p.m., while the SO drove south on Upper Centennial Parkway, just prior to turning right (west) onto Rymal Road East, his speed was 46 km/h but decreased to 35 km/h at 12:48:49 p.m. The speed limit on Upper Centennial Parkway was 60 km/h

- At 12:49:04 p.m., while the SO was travelling west on Rymal Road, his speed increased from 49 km/h to 57 km/h, and

- At 12:49:19 p.m., as the SO approached the intersection of Rymal Road East and Terryberry / Whitedeer Road, his speed decreased from 57 km/h to 29 km/h to 0 km/h

Video/Audio/Photographic Evidence

The SIU canvassed the area for any video or audio recordings, and photographic evidence, but was not able to locate any.

Materials obtained from Police Service

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from HPS:

- Automatic vehicle location/GPS data summary – the SO's cruiser

- Collision statements - CW #4 and another HPS witness

- Communications recordings

- COMM call list spreadsheet

- COMM call table

- Duty roster

- Event chronology

- Motor vehicle collision report

- Notes and Prepared Statements for WO #1 and WO #2

- Occurrence (involvements)

- Occurrence details report

- Policy - suspect apprehension pursuits

- Summary of Interview - HPS witness, and

- Witness statements - CW #5 and four additional HPS witnesses

Relevant legislation

Sections 1-2, Ontario Regulation 266/10, Ontario Police Services Act – Suspect Apprehension Pursuits

(1) For the purposes of this Regulation, a suspect apprehension pursuit occurs when a police officer attempts to direct the driver of a motor vehicle to stop, the driver refuses to obey the officer and the officer pursues in a motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle or identifying the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle

(2) A suspect apprehension pursuit is discontinued when police officers are no longer pursuing a fleeing motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle or identifying the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle.

(1) A police officer may pursue, or continue to pursue, a fleeing motor vehicle that fails to stop

- if the police officer has reason to believe that a criminal offence has been committed or is about to be committed; or

- for the purposes of motor vehicle identification or the identification of an individual in the vehicle

(2) Before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall determine that there are no alternatives available as set out in the written procedures of,

- the police force of the officer established under subsection 6 (1), if the officer is a member of an Ontario police force as defined in the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009

- a police force whose local commander was notified of the appointment of the officer under subsection 6 (1) of the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, if the officer was appointed under Part II of that Act; or

- the local police force of the local commander who appointed the officer under subsection 15 (1) of the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, if the officer was appointed under Part III of that Act

(3) A police officer shall, before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, determine whether in order to protect public safety the immediate need to apprehend an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle or the need to identify the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle outweighs the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit.

(4) During a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall continually reassess the determination made under subsection (3) and shall discontinue the pursuit when the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit outweighs the risk to public safety that may result if an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not immediately apprehended or if the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not identified.

(5) No police officer shall initiate a suspect apprehension pursuit for a non-criminal offence if the identity of an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is known.

(6) A police officer engaging in a suspect apprehension pursuit for a non-criminal offence shall discontinue the pursuit once the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is identified.

Section 249, Criminal Code - Dangerous operation of motor vehicles, vessels and aircraft

(1) Every one commits an offence who operates

- a motor vehicle in a manner that is dangerous to the public, having regard to all the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that at the time is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place…

(3) Every one who commits an offence under subsection (1) and thereby causes bodily harm to any other person is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years.

Analysis and Director’s decision

On December 17th, 2016, at approximately 12:45 p.m., the SO observed a motor vehicle, a black Volvo, being operated by CW #1 on Upper Centennial Parkway and then turn onto Rymal Road East in the City of Hamilton. While following the motor vehicle, the SO queried the licence plate and learned that it was reported as missing; as a result, the SO activated his emergency lights and attempted a traffic stop of CW #1's motor vehicle. CW #1 then increased his speed, turned into the centre left turn lane for both eastbound and westbound traffic, and passed several other motor vehicles. The SO estimated CW #1's speed as between 100 to 120 km/h. Once the SO observed CW #1 increase his speed and pass vehicles in the left turn lane, he deactivated his emergency equipment, abandoned his attempt to stop CW #1 and, instead, strategically followed CW #1's vehicle from a distance and at a far lesser rate of speed.

At the intersection of Rymal Road East and Terryberry/Whitedeer Road, the SO observed CW #1 to enter the intersection against a red light and strike a motor vehicle being operated by the Complainant, who was lawfully proceeding through the intersection on a green light making a left turn onto Rymal Road East. The Complainant sustained a crack to her left shoulder blade as a result of the collision. CW #1 ran from the scene and was later apprehended.

Unfortunately, neither CW #1 nor the SO agreed to an interview with SIU investigators, as was their legal right, and the Complainant had no memory of how she came to be involved in the collision. However, with the assistance of four civilian witnesses, a written statement prepared by the SO, one police witness, the communications recordings and the data from the SO's motor vehicle, the events leading up to the collision between the motor vehicles of CW #1 and the Complainant can be established with a high degree of certainty.

CW #4 confirmed that she observed the SO's cruiser travelling west as she was driving east on Rymal Road East, just west of Upper Centennial Parkway, and that the cruiser's emergency lighting system was activated at that point. She advised that she then observed the emergency lights to be deactivated shortly thereafter. CW #4 advised that she observed the black Volvo driving in front of the SO's cruiser and that he was using the left turning lane to pass other vehicles, was driving at a rate of speed of at least 80 km/h and was weaving in and out of the left turn lane and the live lane of traffic. CW #4 observed that the SO was approximately one car length behind CW #1's vehicle when his emergency equipment was activated, and then deactivated. CW #4 later looked back towards the intersection of Rymal Road East and Terryberry/Whitedeer Road and observed that the SO had reactivated his emergency lighting system at that location.

CW#3, a motorist travelling opposite the Complainant's vehicle through the intersection at Rymal Road East and Terryberry/Whitedeer Road observed CW#1's Volvo being operated on Rymal Road East, east of his location, at a high rate of speed and approach the intersection; CW#3 did not observe any police vehicle at that time. CW#3 observed the Complainant's motor vehicle enter the intersection and begin a left turn onto Rymal Road East, when the Volvo drove through the intersection and collided with the Complainant's vehicle. CW#3 then observed CW#1 exit his motor vehicle and flee the scene.

Equally consistent is the evidence of CW #5, who was driving westbound on Rymal Road East, approaching the red traffic signal at the intersection with Terryberry/Whitedeer Road, when he observed the black Volvo quickly drive past him. He advised that the speed of the Volvo was such that it caused CW #5's motor vehicle to shake. CW #5 then observed the Volvo to enter the intersection and collide with the Complainant's motor vehicle, whereupon CW #1 then exited his vehicle and ran off.

The data from the SO's cruiser confirmed that at 12:48:38 p.m., he was travelling at 46 km/h southbound on Upper Centennial Parkway, just prior to turning west onto Rymal Road East, and then decreased his speed to 35 km/h; as he continued on Rymal Road East, his speed initially increased to 49 km/h and then to 57 km/h. When approaching the intersection of Rymal Road East and Terryberry/Whitedeer Road, his speed decreased at 12:49:19 p.m. to 29 km/h and then came to a complete stop.

From all of the evidence, it appears that the SO observed a motor vehicle being driven with an invalid licence plate and activated his emergency lighting and gave a blast of his siren in order to attempt a traffic stop for an infraction of the Highway Traffic Act (HTA). CW #1, however, then began to drive erratically, accelerated to a speed well in excess of the posted speed limit and was veering in and out of the lane designated for left turns in order to pass other motorists in what appeared to be an attempt to evade police. The cruiser lights, according to civilian witnesses, were activated only for a very short period of time, with one witness estimating no more than ten to fifteen seconds, and were then immediately deactivated as soon as CW #1 entered the left turn lane to pass other motor vehicles. On all of the evidence, it appears that the SO decided to abandon his attempt at a traffic stop, deactivated his emergency lighting and remained in the proper lane of traffic, while CW #1 sped off and was veering in and out of traffic to pass other motorists; the SO, while continuing to travel in the same direction as the Volvo, was travelling at a much lesser rate of speed, and according to the civilian witnesses, was not in view at the instant of the collision and was only seen to slowly approach some period of time thereafter. The evidence further establishes that the SO then came upon the collision scene and observed the Volvo and the Complainant's motor vehicle having been damaged in a collision and stopped to assist the Complainant and CW #2.

It is clear on all of the evidence, that at the time that the SO first observed the motor vehicle driven by CW #1, it was being driven without a proper plate and, as such, the SO was lawfully entitled to stop and investigate the motor vehicle pursuant to the HTA.

I note that the written statement of the SO indicates that the SO was not in a vehicular pursuit at the time of the car collision in which the Complainant was injured, nor had he been in pursuit immediately prior to the collision, having abandoned his efforts to apprehend CW #1 shortly after he initially activated his emergency equipment and attempted to stop CW #1's motor vehicle. His account is fully corroborated by the four civilian witnesses who observed either the attempted traffic stop or the subsequent collision. On all of the evidence, it is clear that although the SO initially attempted to bring CW #1's vehicle to a stop, which he was lawfully entitled to do, at no time did he shorten the gap between his own vehicle and that of CW #1 and, after CW #1 entered the lane designated for left turns in order to overtake and pass other motor vehicles on the roadway, the SO de-activated his emergency equipment and the Volvo was apparently lost from view. It is clear from the evidence of two of the civilian witnesses, that within seconds of the SO activating his emergency equipment, he deactivated his equipment and allowed CW #1 to drive away. From the point where the SO first attempted a traffic stop, until the point where the SO deactivated his emergency equipment and pulled back into traffic, the distance covered was estimated by witnesses to have been no more than between 170 and 290 metres. From the time when the emergency equipment was deactivated, until the time of CW #1's collision, approximately a further 750 metres had been travelled by CW #1. As such, I can find no causal connection between the driving of the SO and the injuries sustained by the Complainant, which are solely attributable to the reckless driving of CW #1.

It is worthy of note that the SO fully complied with Ontario Regulation 266/10 of the Ontario Police Services Act (OPSA) entitled Suspect Apprehension Pursuits, in that, within seconds of attempting a traffic stop of CW #1's vehicle, he abandoned his efforts, deactivated his emergency equipment and allowed CW #1 to accelerate away without interference. It can be inferred on this evidence that the SO considered whether in order to protect public safety, the immediate need to apprehend an individual in a fleeing motor vehicle, or the need to identify a fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in a fleeing motor vehicle, outweighed the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit (s.2(3)) and determined that it did not.

The final question to be determined is whether or not there are reasonable grounds to believe that the SO, in his attempt to stop CW #1, committed a criminal offence, specifically, whether or not his driving rose to the level of being dangerous and therefore in contravention of s.249(1) of the Criminal Code.

The decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Beatty, [2008] 1 S.C.R. 49, sets out the law with respect to s.249 in that it requires that "the driving be dangerous to the public, having regard to all of the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that, at the time, is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place" and the driving must be such that it amounts to "a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the accused's circumstances".

On a review of all of the evidence, I find that there is no evidence that the driving of the SO created a danger to other users of the roadway or that at any time did he interfere with other traffic; he used his emergency equipment prudently, initially activating his emergency equipment to attempt to stop CW #1, but immediately deactivated his equipment when it became clear that CW #1 was not going to stop; the environmental conditions were good and the roads were dry.[5] Furthermore, the evidence establishes that the SO did nothing to exacerbate the Volvo's pattern of dangerous driving; it is clear that CW #1 continued speeding, driving erratically and ran the red light at Rymal Road East and Terryberry/Whitedeer Road long after the SO had deactivated his emergency lighting and abandoned any attempt to stop CW #1. On this evidence, it is clear that CW #1 had made a voluntary decision to drive in the manner that he did in order to evade police, and that he continued to do so both when the officer attempted to stop him and after the officer had abandoned his intention in the interests of public safety and the Volvo was lost from view.

As such, I find that the evidence of the SO's driving does not rise to the level of driving required to constitute "a marked departure from the norm" and, as indicated earlier, there is no evidence to support a causal connection between the actions of the SO and the motor vehicle collision caused by CW #1 entering the intersection. In fact, in reviewing the evidence in its entirety, it is clear that not only did the SO respond to the situation in full compliance with the Criminal Code, the HTA and the OPSA, but he behaved at all times professionally, prudently and with good common sense. I cannot find any criticism of the SO's actions and, as such, find that there is absolutely no basis here for the laying of criminal charges.

Date: November 28, 2017

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Endnotes

- 1) [1] Terryberry Road is south of Rymal Road. Whitedeer Road is north of Rymal Road. [Back to text]

- 2) [2] On Feb 2, 2017, at 1:50 p.m., SIU investigators met with CW #1 in custody. He did not provide a statement. [Back to text]

- 3) [3] CW #4 and CW #5 were interviewed by HPS, and those statements were provided to the SIU. [Back to text]

- 4) [4] WO #3’s notes indicated that he arrived at the scene after the collision to transport the SO to the station. WO #3 and the SO did not discuss the details of the incident. [Back to text]

- 5) [5] However, by way of contrast, CW #4 in her statement to HPS indicated that the roads were wet and slushy and traffic was steady. [Back to text]

Note:

The signed English original report is authoritative, and any discrepancy between that report and the French and English online versions should be resolved in favour of the original English report.