SIU Director’s Report - Case # 20-OFD-075

Warning:

This page contains graphic content that can shock, offend and upset.

Contents:

Mandate of the SIU

The Special Investigations Unit is a civilian law enforcement agency that investigates incidents involving police officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The Unit’s jurisdiction covers more than 50 municipal, regional and provincial police services across Ontario.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Information Restrictions

Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (“FIPPA”)

Pursuant to section 14 of FIPPA (i.e., law enforcement), certain information may not be included in this report. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:- Confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by law enforcement agencies; and

- Information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding.

- Subject Officer name(s);

- Witness Officer name(s);

- Civilian Witness name(s);

- Location information;

- Witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence; and

- Other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation.

Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 (“PHIPA”)

Pursuant to PHIPA, any information related to the personal health of identifiable individuals is not included. Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from this report because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner’s inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.Mandate Engaged

The Unit’s investigative jurisdiction is limited to those incidents where there is a serious injury (including sexual assault allegations) or death in cases involving the police.

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the shooting death of D’Andre Campbell during an interaction with Peel Regional Police (PRP) in Brampton.

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the shooting death of D’Andre Campbell during an interaction with Peel Regional Police (PRP) in Brampton.

The Investigation

Notification of the SIU

At about 6:43 p.m. of April 6, 2020, the PRP contacted the SIU to report that, at approximately 5:56 p.m., the Subject Officer (SO) and Witness Officer (WO) #2 responded to a domestic disturbance in progress in Brampton. There they encountered D’Andre Campbell, who was fighting with his mother. Mr. Campbell became violent towards the officers and they both attempted to subdue him with Conducted Energy Weapons (CEWs). This was ineffective and the SO drew his firearm and shot Mr. Campbell. Mr. Campbell died at the scene.

The Team

Number of SIU Investigators assigned: 4 Number of SIU Forensic Investigators assigned: 4

Complainant:

D’Andre Campbell 26-year-old male, deceasedCivilian Witnesses

CW #1 (Father) Interviewed CW #2 (Mother) Interviewed

CW #3 (Sister) Interviewed

CW #4 (Sister) Interviewed

Witness Officers

WO #1 Interviewed WO #2 Interviewed

WO #3 Interviewed

WO #4 Interviewed

Subject Officers

SO Declined interview and to provide notes, as is the subject officer’s legal rightEvidence

The Scene

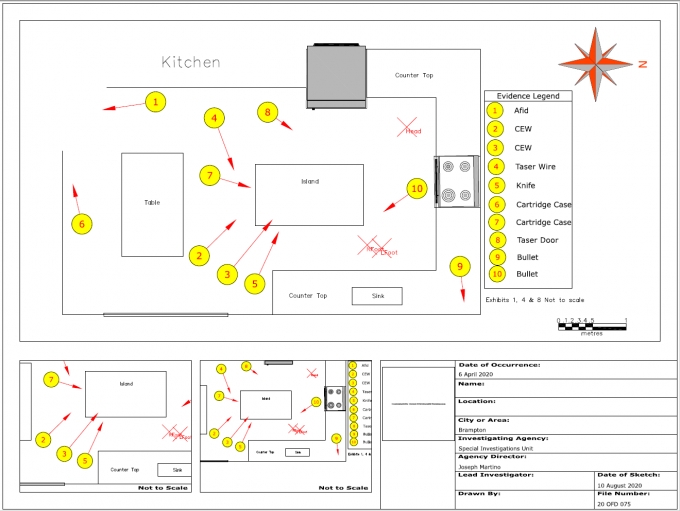

At 9:29 p.m., an SIU Forensic Investigator arrived at an address on Sawston Circle, Brampton, consisting of a single detached-dwelling with two stories. The incident took place in the kitchen of the dwelling, which contained a table and four chairs at the south end, and centre island, along with the usual kitchen appliances. Mr. Campbell was located in the kitchen, lying on his back on the floor on the north end of the island beside the stove. Mr. Campbell was clothed, and there were several items of a medical nature around his body. A number of items were observed and collected from the kitchen. These included numerous yellow and pink CEW Anti-Felon Identification Tags; two yellow CEWs on the floor by the southeast corner of the island; CEW wires; a silver knife with an overall length of 33.5 cm and a blade length of 19.5 cm located on the southeast corner of the island; one silver spent .40 cal cartridge case located on the floor at the south end of the kitchen; and, another silver spent .40 cal cartridge case located on the floor at the south end of the island. Two projectiles were located in the kitchen, one on the kitchen counter in the northeast corner of the kitchen behind a ceramic plate and stand, and one on the tile floor underneath the right calf of Mr. Campbell.

Figure 1 - The silver kitchen knife was located next to a CEW and CEW wires.

Figure 2 - The location of the second CEW (2) and a cartridge case (7).

Figure 3 - The second cartridge case.

Scene Diagram

Physical Evidence

An SIU Forensic Investigator examined and photographed the following items in the possession of the SO: - Police issued cargo pants with a red/brown-coloured stain visible on the right pant leg in the knee area and shin and cuff area. A red/brown-coloured stain was also visible on the left pant leg in the thigh area.

- A CEW probe and wire attached to a black PRP toque. These items, along with a disposable mask, were resting in the left cargo pocket. A pair of black search gloves in the right cargo pocket. Police boots with a red/brown-coloured stain on the outer area near the toe cap of the left boot and two red/brown-coloured stains visible on the lower instep area, near eyelets of the left boot.

- A ballistic vest and a police duty belt with the CEW holster empty.

- A police-issued firearm, a Smith and Wesson M&P 40, was in its holster. The pistol had one unfired cartridge chambered, and the magazine in the pistol had thirteen unfired cartridges. Two spare pistol magazines were in their designated pouches; both contained fifteen unfired cartridges.

Figure 4 - The SO's firearm.

Forensic Evidence

CEW Data Summaries

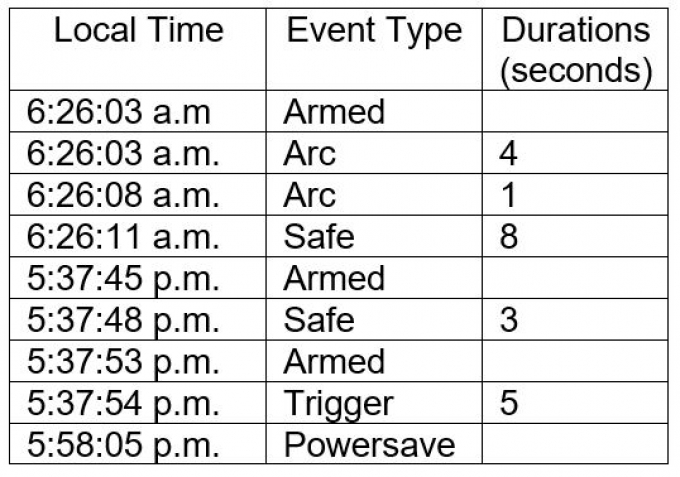

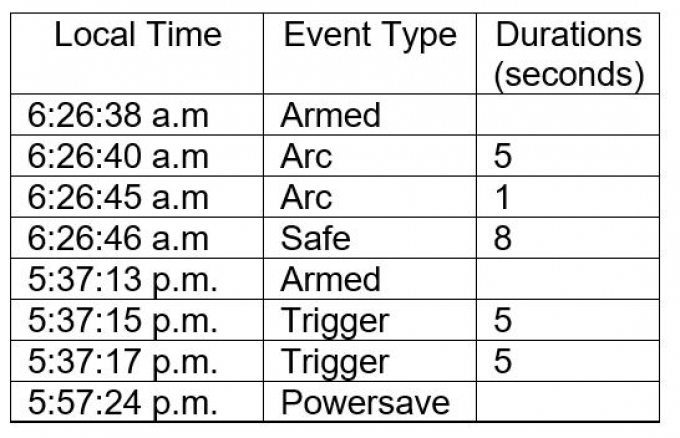

WO #2’s CEW Download

SO’s CEW Download

Centre of Forensic Sciences (CFS) Submissions and Results

The projectiles were .40 calibre class jacketed hollow point bullets. They were fired from a firearm rifled with five lands and grooves, right hand twist. They were microscopically examined and compared to test fired bullets generated by the SO’s pistol. The test fired projectiles generated by the SO’s pistol were microscopically examined and compared to projectiles recovered on scene. There was an agreement of class and individual characteristics between the items.

The SIU also submitted a red-stained white T-shirt worn by Mr. Campbell, and two bullets and two spent cartridge cases recovered from the scene to determine whether or not firearm discharge residues were present and, if so, to determine the muzzle to target distance of the firearm to the garment at the time of firing.

The T-shirt was examined visually, microscopically, and with infrared photography. Multiple defects were observed on the front and back of the T-shirt. Some appeared to be associated with CEW probes. No firearm discharge residues were observed [2] surrounding the defects; therefore, no further examinations were conducted.

Communications Recordings

Summary of 911 Calls & Police Radio Communications

911 Calls

Track 01 The caller says they need the police to come to Brampton, then hangs up.

Track 02 911 attempts to call back and gets voice-mail of a woman;

Track 03 911 attempts to call back, speaks to the woman - a neighbour; she is out of breath and, when asked, does not provide her address.

Track 04 911 attempts to call back (presumably to the woman); no answer.

Track 05 911 attempts to call back (presumably to the woman); voice-mail starts followed by 911 hanging up.

Track 06 Inaudible; sounds like 911 calling internally within PRP to advise, “Shots fired.”

Track 07 911 to ambulance, “[N]eed you on a rush… shot twice” at [Mr. Campbell’s address].

Track 08 911 speaks to a male within the PRP, advising that shots were fired and it is unknown by whom.

Track 09 Frantic female says her brother called the police, that police came, he had a weapon but they tried to stop him, and they ended up shooting him. The caller is calling from outside the home and says, “They shot him twice…”.

Track 10 A woman from communications speaks to a male within PRP, asking if he is listening [to radio call]. He replies in the affirmative.

Track 11 Communicator advises a female from PRP of directions to [the scene]; communicator mentions that an [emergency request for assistance] went off followed by reports of shots fired.

Track 12 PRP speaks to ambulance, requesting an estimated time to arrival.

Track 13 A Criminal Investigation Branch officer logs on via telephone.

Track 14 PRP officer from Track 11 asks communicator to forward an incident history to another person.

Track 15 A male inquires if the incident was an officer-involved shooting. Communicator indicates, “There was a [emergency request for assistance] … and then she said, ‘Shots fired.’”

Police Radio Communications

Track 01 Reference to the male being vital signs absent (VSA) and Emergency Medical Services still working.

Track 04 Transmission noting that male was “pronounced” at 6:01 p.m.

Track 05 Transmission indicating that WO #2 and the SO are being transported to the station by different officers.

Track 06 Transmission indicating that [transmissions being stopped due to an emergency] is no longer required.

Track 7-20 Miscellaneous communications about staffing; nothing specific to involved officers or the shooting.

Track 21 [3] Communicator dispatches a “priority call in the 440 area, domestic at [the scene]. Belligerent male on the line swearing saying get the police there right now, telling us that his parents are trying to start an argument with him”.

Track 22 Communicator advises responding officers that the male caller [now known to be Mr. Campbell] is “cautioned [armed and dangerous, escape risk, violent or aggressive]” and suffers from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. She further indicates that police last attended the residence in February 2019 for a mentally ill person, Mr. Campbell, who was born in 1993. He was arrested on that occasion after attempting to fight family members. The communicator notes that Mr. Campbell was not taking his medication at the time. WO #2 acknowledges receipt of the information.

Track 23 Male voice [thought to be the SO] says both units were [on scene].

Track 24 Very loud repetitive beeping sound is heard. Communicator announces a [emergency request for assistance] from WO #2. A male voice is heard to say, “Shots fired.” Communicator announces the location of call to all units and directs [there be no communication due to an emergency]. A person, believed to be WO #2, reports, “Male party shot been shot approximately two times in the chest.”

Track 25 Transmission indicating that [a unit] is on scene;

Track 26 Transmission from [the unit] reporting that “both the officers are [okay], we’ve got a male with gunshot wound”.

Track 27-31 Various units book off at [the scene].

Track 32 Unknown officer reports, “[L]arge kitchen knife laying on the kitchen (garbled).”

Track 33 Officer states, “Commencing CPR. Shot twice, faint pulse”.

Track 34 Officer states, “Residence being cleared”.

Track 35 Ambulance is [on-scene].

Track 36 Officer notes that male has “… just gone VSA”.

Police Service Policies

The SIU obtained the PRP Directive, entitled “Mental Health Policy”, in effect at the time of this incident. The directive provides that it is the policy of the PRP to “work in partnership with community mental health agencies in an effort to reduce the stigma and impact of mental illness in society and to share responsibility for improving the quality of life for the mentally ill and developmentally challenged.”One of the ways the policy seeks to further its objectives is through COAST, or the Crisis Outreach Assessment Support Team. COAST consists of an officer working in plainclothes and in an unmarked cruiser with a mental health professional. The COAST service is available on a 24/7 basis. Calls into the PRP call centre that may involve an emotionally disturbed person or someone with a mental illness or disorder are assessed by the call takers for possible referral to COAST. In making that determination, the call-taker considers whether:

- The call involves someone 16 years of age and over with a mental illness;

- The call is not of an emergent nature;

- There are no weapons involved in the call; and

- The situation is calm.

If a call for service does not qualify for referral to COAST, the call-taker is required to dispatch two officers to the scene providing them all information they were able to glean from the caller. [4]

The responsibility of COAST officers are enumerated in the policy, and include the following:

- Work as part of a two person mobile team consisting of an officer and mental health professional;

- Ensure the safety and security of police, the mental health professional and the client; and

- Respond to mental health crisis calls within the Region of Peel.

Other than COAST, officers responding to calls for service from the general community involving a person who “lives with [sic], or is believed to be currently in crisis, or upon encountering such a person,” are provided guidance regarding the nature of their response. For example, they are to:

- Ensure that there is sufficient assistance;

- Approach the person in a manner as follows:

o No quick or sudden movements;o Tell the person who you are, and why you are there, that you are there to help;o Speak with simple, clear language (you may need to repeat yourself);o Explain your actions before you do them;o Take your time and ask questions (e.g. are you hurt, how can I help you, are you hearing voices); ando Remove any outside stimuli (e.g. turn off television or radio);

- Search the area and person, if possible for weapons;

- Attempt to ascertain if the person has taken any prescribed medication and/or illicit drugs;

- Speak to the person’s family and/or caregivers to investigate the person’s behavioural and medical history; and

- If the situation fits the criteria for COAST officer attendance, request his/her attendance through the communications centre.

Materials obtained from Police Service

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the PRP:- Communications recordings;

- Computer Assisted Dispatch Report;

- Event Details Report;

- Notes of the witness officers

- Person Details (Mr. Campbell);

- Occurrence Report (x9);

- PRP Directive – Mental Health Policy (effective date October 26, 2018);

- PRP Communication Centre Manual – COAST (Crisis Outreach Assessment Support Team); and

- Reports related to WO #2’s and the SO’s CEWs.

Materials obtained from Other Sources

The SIU also obtained the following records from other sources:- Report of Postmortem Examination, dated June 24, 2020, from the Coroner’s Office; and

- Centre of Forensic Sciences Firearms Report, dated June 19, 2020.

Incident Narrative

While there is conflict in the evidence regarding the penultimate moments before the shooting, the following scenario emerges from the weight of the information collected by the SIU, which included interviews with members of Mr. Campbell’s family present at the time of the incident and WO #2, together with the SO throughout the events in question. The investigation also benefitted from a forensic examination of the incident scene and items of evidence, the results of the postmortem examination, the data downloaded from two CEWs that had been deployed, and a review of police communications recordings. As was his legal right, the SO declined to interview with the SIU and release a copy of his incident notes.

At about 5:34 p.m. of April 6, 2020, the SO and WO #2 arrived at the front door of Mr. Campbell’s residence. They had been dispatched following a 911 call to police by Mr. Campbell. In the call, an agitated Mr. Campbell reported that his parents were trying to start an argument with him, and demanded that police attend the residence as soon as possible. When asked for his address, Mr. Campbell refused to provide one and said that the police had a tracking system on him and knew where he lived. The police were able to quickly identify his location and officers were dispatched to investigate the situation.

Mr. Campbell had been the subject of multiple police checks at the residence over the years, many of which were the result of his struggles with mental illness. Between about 2011 and 2014, police were at the home on at least five occasions dealing with problems associated with Mr. Campbell’s mental health. In October 2011, for example, officers apprehended Mr. Campbell under the Mental Health Act when a family member called to report that Mr. Campbell was acting strangely and they was concerned for their safety. Mr. Campbell was again taken into custody under the Mental Health Act in 2014 following a call to police by a family member. On other occasions, the PRP COAST (Crisis Outreach Assessment Support Team) team had attended, assessed the situation and left without any apprehensions under the Mental Health Act. COAST is a partnership between PRP and the Canadian Mental Health Association (Peel-Dufferin) which aims to provide non-emergency response to people experiencing mental health or addiction-based crisis through support teams that consist of plainclothes officers and a mental health professional.

Mr. Campbell’s mother, CW #2, allowed the officers entry into the home. The parties spoke briefly in the foyer, CW #2 indicating that Mr. Campbell had mental health issues and there had been an argument in the home, before they made their way into the kitchen at the end of the hallway.

Mr. Campbell was present in the kitchen at the time. He was standing and facing the officers holding a knife in his right hand by the counter along the east wall of the kitchen. A centre kitchen island was positioned between the officers and Mr. Campbell.

At the sight of the knife, the SO and WO #2 each drew their CEWs and pointed them at Mr. Campbell. The SO repeatedly ordered Mr. Campbell to drop the knife. With knife in hand, Mr. Campbell walked toward the officers. When he had neared to within a metre or so of the SO, the officer fired his CEW twice. Mr. Campbell fell backward against the side of the refrigerator and then onto the floor.

Following his CEW deployment, the SO put his weapon aside and moved forward to physically engage Mr. Campbell, who was still holding the knife in his right hand. There ensued a struggle of some duration between the two, most if not all of which seems to have occurred over top of the refrigerator’s open bottom mount freezer drawer. As the struggle unfolded, WO #2, from a position south of the parties, fired her CEW at Mr. Campbell. The discharge failed to incapacitate Mr. Campbell, who continued to struggle with the SO. In fact, there is some evidence that one of the CEW’s probes actually struck the SO.

The SO and Mr. Campbell eventually disentangled and gained their footing whereupon Mr. Campbell returned to a position across the kitchen island from both officers. He stood facing the officers with the knife still in his right hand. The SO and WO #2 drew their firearms and pointed them at Mr. Campbell. Within seconds, the SO fired his weapon twice in rapid succession, striking Mr. Campbell in the abdomen.

Mr. Campbell collapsed to the floor, his backside against the oven north of the kitchen island. The officers approached Mr. Campbell and rendered first aid. WO #2 attempted to stem the bleeding from Mr. Campbell’s wounds with paper towels as the SO spoke with him trying to keep him conscious. The officers radioed that shots had been fired, and paramedics and other first responders began to make their way to the scene. When he could no longer detect a pulse from Mr. Campbell, the SO began CPR.

The attending paramedics continued with life-saving measures but were unsuccessful in resuscitating Mr. Campbell. Mr. Campbell was pronounced deceased at 6:01 p.m.

Cause of Death

The pathologist at autopsy concluded that Mr. Campbell’s death was attributable to “perforating gunshot wounds of the abdomen”. One of the two bullets had entered Mr. Campbell’s right central abdomen and exited the left lower back. This bullet travelled front to back, right to left, and slightly downward, and resulted in fatal internal injuries. The other bullet entered Mr. Campbell’s right lateral abdomen and exited the lower central back. It too travelled front to back, right to left, and slightly downward. The injuries caused by this bullet would likely have been non-fatal, in the pathologist’s opinion, with medical attention.

At about 5:34 p.m. of April 6, 2020, the SO and WO #2 arrived at the front door of Mr. Campbell’s residence. They had been dispatched following a 911 call to police by Mr. Campbell. In the call, an agitated Mr. Campbell reported that his parents were trying to start an argument with him, and demanded that police attend the residence as soon as possible. When asked for his address, Mr. Campbell refused to provide one and said that the police had a tracking system on him and knew where he lived. The police were able to quickly identify his location and officers were dispatched to investigate the situation.

Mr. Campbell had been the subject of multiple police checks at the residence over the years, many of which were the result of his struggles with mental illness. Between about 2011 and 2014, police were at the home on at least five occasions dealing with problems associated with Mr. Campbell’s mental health. In October 2011, for example, officers apprehended Mr. Campbell under the Mental Health Act when a family member called to report that Mr. Campbell was acting strangely and they was concerned for their safety. Mr. Campbell was again taken into custody under the Mental Health Act in 2014 following a call to police by a family member. On other occasions, the PRP COAST (Crisis Outreach Assessment Support Team) team had attended, assessed the situation and left without any apprehensions under the Mental Health Act. COAST is a partnership between PRP and the Canadian Mental Health Association (Peel-Dufferin) which aims to provide non-emergency response to people experiencing mental health or addiction-based crisis through support teams that consist of plainclothes officers and a mental health professional.

Mr. Campbell’s mother, CW #2, allowed the officers entry into the home. The parties spoke briefly in the foyer, CW #2 indicating that Mr. Campbell had mental health issues and there had been an argument in the home, before they made their way into the kitchen at the end of the hallway.

Mr. Campbell was present in the kitchen at the time. He was standing and facing the officers holding a knife in his right hand by the counter along the east wall of the kitchen. A centre kitchen island was positioned between the officers and Mr. Campbell.

At the sight of the knife, the SO and WO #2 each drew their CEWs and pointed them at Mr. Campbell. The SO repeatedly ordered Mr. Campbell to drop the knife. With knife in hand, Mr. Campbell walked toward the officers. When he had neared to within a metre or so of the SO, the officer fired his CEW twice. Mr. Campbell fell backward against the side of the refrigerator and then onto the floor.

Following his CEW deployment, the SO put his weapon aside and moved forward to physically engage Mr. Campbell, who was still holding the knife in his right hand. There ensued a struggle of some duration between the two, most if not all of which seems to have occurred over top of the refrigerator’s open bottom mount freezer drawer. As the struggle unfolded, WO #2, from a position south of the parties, fired her CEW at Mr. Campbell. The discharge failed to incapacitate Mr. Campbell, who continued to struggle with the SO. In fact, there is some evidence that one of the CEW’s probes actually struck the SO.

The SO and Mr. Campbell eventually disentangled and gained their footing whereupon Mr. Campbell returned to a position across the kitchen island from both officers. He stood facing the officers with the knife still in his right hand. The SO and WO #2 drew their firearms and pointed them at Mr. Campbell. Within seconds, the SO fired his weapon twice in rapid succession, striking Mr. Campbell in the abdomen.

Mr. Campbell collapsed to the floor, his backside against the oven north of the kitchen island. The officers approached Mr. Campbell and rendered first aid. WO #2 attempted to stem the bleeding from Mr. Campbell’s wounds with paper towels as the SO spoke with him trying to keep him conscious. The officers radioed that shots had been fired, and paramedics and other first responders began to make their way to the scene. When he could no longer detect a pulse from Mr. Campbell, the SO began CPR.

The attending paramedics continued with life-saving measures but were unsuccessful in resuscitating Mr. Campbell. Mr. Campbell was pronounced deceased at 6:01 p.m.

Cause of Death

Relevant Legislation

Section 34, Criminal Code -- Defence of person - Use of threat of force

34 (1) A person is not guilty of an offence if

(a) They believe on reasonable grounds that force is being used against them or another person or that a threat of force is being made against them or another person;(b) The act that constitutes the offence is committed for the purpose of defending or protecting themselves or the other person from that use or threat of force; and(c) The act committed is reasonable in the circumstances.

(2) In determining whether the act committed is reasonable in the circumstances, the court shall consider the relevant circumstances of the person, the other parties and the act, including, but not limited to, the following factors:

(a) the nature of the force or threat;(b) the extent to which the use of force was imminent and whether there were other means available to respond to the potential use of force;(c) the person’s role in the incident;(d) whether any party to the incident used or threatened to use a weapon;(e) the size, age, gender and physical capabilities of the parties to the incident;(f) the nature, duration and history of any relationship between the parties to the incident, including any prior use or threat of force and the nature of that force or threat;(f.1) any history of interaction or communication between the parties to the incident;(g) the nature and proportionality of the person’s response to the use or threat of force; and(h) whether the act committed was in response to a use or threat of force that the person knew was lawful.

Analysis and Director's Decision

In the evening of April 6, 2020, D’Andre Campbell lost his life after being shot by a PRP officer. The shooting incident occurred inside Mr. Campbell’s home on Sawston Circle, Brampton. Officers had been dispatched to the address following a 911 call to police from Mr. Campbell complaining about his parents. Among the two officers who arrived at the residence was the SO. It was the SO who discharged his firearm at Mr. Campbell; accordingly, the officer was identified as the subject officer for purposes of the SIU investigation. On my assessment of the evidence gathered in the investigation, which has now concluded, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the SO committed a criminal offence in connection with Mr. Campbell’s death.

Section 34 of the Criminal Code sets out the circumstances in which conduct that would otherwise constitute an offence is legally justified in defence of oneself or another. It provides that a person may use force to repel a reasonably apprehended attack, actual or threatened, as long as the force is reasonable. The reasonableness of the force in question is to be measured on the basis of the relevant circumstances that prevailed at the time, including such considerations as the nature of the force or threat; the extent to which the use of force was imminent and whether there were other means available to respond to the potential use of force; whether any party to the incident used or threatened to use a weapon; and, the nature and proportionality of the person’s response to the use or threat of force. Upon careful consideration of the evidence collected by the SIU, I am unable to reasonably conclude that the force used by the SO fell outside the ambit of section 34’s protection.

I have little doubt that the SO believed he was acting in self-defence, and perhaps in defence of his partner, WO #2, when he discharged his firearm at Mr. Campbell. The SO did not avail himself of an interview with the SIU, which was his legal right. Of course, that means there is no direct evidence regarding the officer’s mindset at the time of the shooting. Nevertheless, there is nothing in the circumstantial evidence, to be explored below, that would cause me to believe the SO was without a genuine belief that he was acting to protect himself, and plenty in that same body of evidence to strongly suggest that was precisely what he was doing. The real issue, in my view, is whether the SO’s apprehensions, and the shooting they precipitated, were reasonable in the circumstances.

Before turning to the reasonableness analysis, it should be noted that the officers were lawfully present inside the kitchen. They had been called to the home by Mr. Campbell and were let into the house by CW #2. They were duty bound, in the circumstances, to investigate the reported domestic disturbance that had prompted Mr. Campbell’s call and thus were within their rights to follow CW #2 into the kitchen.

There is a strong case to be made that the SO reasonably believed that he needed to fire his gun to protect himself against the imminent risk of a knife attack at the hands of Mr. Campbell. Mr. Campbell had in his possession a dangerous weapon – a knife with a long blade – that could be used to inflict grievous bodily harm or death. By the time of the shooting, the officers had been unable to dispossess Mr. Campbell of the knife despite repeated direction that he drop it, several CEW discharges (one or more of which that might have successfully connected), and a physical struggle on the kitchen floor. It did not appear that Mr. Campbell was about to voluntarily surrender the knife.

It is also likely, in my view, that Mr. Campbell had obtained the knife in order to wield it as a weapon. While there was some evidence that Mr. Campbell simply had the knife in his hands because he was using it to prepare food in the kitchen, the weight of the evidence, including that coming from some members of the Campbell family, suggests that he had retrieved it just before the officers’ entry into the kitchen in order to confront them with it. For example, CW #2 noted that Mr. Campbell was not in the kitchen when she left to answer the officers’ knock on the door. In addition, CW #4 says she overheard her mother asking Mr. Campbell why he had a knife as she (CW #2) and the officers entered the kitchen. This same evidence lends credence to WO #2’s account of the manner in which Mr. Campbell was holding the knife when they first saw him and then again just before he was shot, namely, up by his chest area and pointed toward the officers, albeit it must be acknowledged that there is contrary evidence in this area. Mr. Campbell’s sisters, CW #3 and CW #4, each say that Mr. Campbell’s arms were down by his side just before he was shot.

With respect to whether there were alternatives other than a resort to lethal force, it is arguable whether the officers, confronted by an individual holding a knife, ought to have withdrawn from the kitchen. It is conceivable that a retreat of some extent might have de-escalated the situation and averted a physical and, ultimately, lethal confrontation. Instead, as it turned out, the SO immediately began to yell at Mr. Campbell upon entering the kitchen to drop the knife while pointing a CEW at him, quickly turning the interaction into an armed standoff. On the one hand, the SO and WO #2 had no reason to believe that there had been any violence involving Mr. Campbell and members of his family prior to their arrival and, therefore, some basis to conclude that the balance of risks favoured disengagement. On the other hand, if Mr. Campbell had given no indication of violence ahead of their arrival, the same cannot be said once the officers were in the kitchen. More to the point, Mr. Campbell’s presence in the kitchen with a large knife and steadfast refusal to drop it would have impressed on the officers that he was capable of inflicting harm on them. But not only them, on Mr. Campbell’s family as well; after all, it was Mr. Campbell who had demanded that the police attend his residence to assist in an argument with his parents. I am further satisfied that withdrawal would not have been a simple matter. Given the confined space in which Mr. Campbell and the officers found themselves, it is not readily apparent that the officers had the necessary freedom of movement to safely and successfully remove themselves from the kitchen. In the circumstances, I am unable to dismiss as unreasonable the officers’ decision to stand their ground.

Finally, whether Mr. Campbell moved toward the officers just before he was shot is an important part of the inquiry and also the subject of discrepant accounts in the evidence. CW #3 and CW #4 maintain that their brother was standing in place, not having made any movements toward the officers, when the SO discharged his firearm. In contrast, WO #2 says that Mr. Campbell took one or two deliberate steps forward before he was shot. I am unable to resolve this conflict in the evidence. While there is evidence that CW #3 was not in the kitchen at the time of the shooting, I have no reason to question the veracity of CW #4’s description of her brother’s movements. Similarly, there is nothing in the evidence to cast doubt on the credibility of WO #2’s evidence. Accordingly, I accept that there is some evidence to reasonably conclude that Mr. Campbell had not in fact advanced upon the SO when he was shot. That conclusion, however, is not the end of the analysis.

In the fraught atmosphere that prevailed at the time, it is entirely plausible that a reasonable person in the SO’s shoes would believe that he or she was at immediate risk of a knife attack by Mr. Campbell when the officer discharged his firearm, whether or not Mr. Campbell had taken any steps toward him. The weight of the evidence, for example, establishes that Mr. Campbell was at the very least swaying on his feet when he was shot. It may be that Mr. Campbell was doing so not with any malevolent intention but simply because he had just been “tasered” and was therefore naturally unsteady on his feet. However, the suggestion does not detract from the distinct possibility that Mr. Campbell’s gestures led the SO to reasonably believe that he was on the verge of being attacked.

On the aforementioned-record, I am unable to reasonably conclude with any confidence that the SO acted without legal justification when he shot Mr. Campbell. On the contrary, the evidence suggests that the SO credibly believed at the time that he was confronted with a real and present danger to life and limb, and that his use of force was reasonable in the circumstances. Though faced with an individual wielding a large knife in his direction, the SO did not immediately draw his firearm. Rather, as with his partner, WO #2, the officer pointed his CEW at Mr. Campbell and directed him to drop the knife. It was only after several CEW discharges and a physical struggle on the floor had failed to dispossess Mr. Campbell of the knife that the SO drew his firearm. Whether in the cold light of hindsight it can be said that shooting Mr. Campbell was absolutely necessary in the moment to protect the SO or his partner from an immediate risk of death or grievous bodily arm is arguable. To reiterate, there is evidence that Mr. Campbell had not made any movement to close the distance between him and the officers when the shots were fired. That said, Mr. Campbell was already in close proximity to the SO when the SO discharged his firearm. In the context of what was a highly dynamic and violent confrontation with an individual brandishing a knife, I am satisfied that there is insufficient evidence to reasonably establish that the SO’s gunfire amounted to an unlawful use of force. [5]

This case and others raise important and systemic issues about the manner in which police respond to mental health calls. This was one such call. While en route to Mr. Campbell’s residence, the SO and WO #2 were advised that Mr. Campbell suffered from mental illness, specifically, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. They were also informed that the police had last been to the address in February 2019 as Mr. Campbell had not been taking his medication and was being aggressive with family members.

The SIU’s statutory mandate, however, is a narrow one. It is to determine whether there are reasonable grounds to believe that a criminal offence has been committed by applying the law as it stands to the facts as they are discerned, not to delve into broader public policy considerations that may be implicated in any particular case. There are other bodies with the institutional mandates and competence to conduct those reviews. This does not mean that questions of mental health that are raised in the specific circumstances of an incident are not relevant in a criminal investigation; of course, they may well be. It does mean that care must be taken to ensure that the inquiry remains focused on the conduct of the individuals, not the merits or failings of the system within which they operate.

In the instant case, the conduct of the SO and WO #2 in the lead-up to the encounter with Mr. Campbell is in some ways subject to legitimate criticism. Though they knew that Mr. Campbell suffered from mental illness and was likely in an agitated condition, they did not confer with each other about the approach they would take once inside the home. Thus, there was no talk of how they would react in the face of various contingencies, such as who between them would take the lead in dealing with Mr. Campbell or how de-escalation might be pursued should the need present itself. Whether those conversations would have made a difference to the outcome is speculation, but the officers’ failure to have that discussion limited their ability to consider alternative strategies. Moreover, once in the kitchen, the SO immediately began to order Mr. Campbell to put the knife down. At no point was there any effort made to verbally calm Mr. Campbell.

The offence that arises for consideration in light of this conduct is criminal negligence causing death contrary to section 220 of the Criminal Code. The offence is predicated, in part, on conduct that constitutes a marked and substantial departure from the level of care that a reasonable person would have exercised in the circumstances. In my view, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the officers transgressed the limits of care prescribed by the criminal law in the moments before their standoff with Mr. Campbell. Thus, while the officers perhaps should have done more to take stock of the situation before they knocked on the door, it is not as if the officers entered the home without some appreciation of what they might encounter. WO #2, for example, says she was cognizant of the fact there were no sounds of a disturbance coming from the house as they knocked on the front door. Once through the door, there were also no signs of trouble in the household. CW #2 confirmed that there had been an argument involving Mr. Campbell and that he suffered from mental illness, but otherwise everything appeared calm. Finally, with respect to the tact adopted by the officers upon seeing Mr. Campbell, their failure to meaningfully engage in any efforts to talk Mr. Campbell down is tempered by the fact that they were being confronted by an individual pointing a knife in their direction. On this record, if there were lapses in judgment on the part of WO #2 or the SO, they were neither reckless nor wanton in the circumstances.

There remains the question of the potential deployment of the PRP Crisis Outreach Assessment Support Team, or COAST. Each COAST unit pairs a plainclothes officer with a mental health professional, who are available to respond to calls on a 24-7 basis. COAST is a method by which the police service seeks to respond more effectively to calls for service involving persons experiencing mental health crisis or emotional distress. However, pursuant to the PRP policy in effect at the time, COAST units are not mobilized unless the following four conditions are met: the call involves someone 16 years of age and over who is experiencing a mental health issue; the call is not of an emergent nature; there are no weapons involved in the call; and, the situation is calm.

I am unable to find fault with the decision not to deploy the COAST team in response to Mr. Campbell’s 911 call to police. The police call-takers, who are responsible for deciding whether or not COAST involvement is appropriate, are tasked with gathering information from the caller with which to make the assessment. These inquiries include whether the person experiencing crisis is armed or has access to weapons. The call-taker who took Mr. Campbell’s call, however, was unable to obtain this information as Mr. Campbell, perhaps through no fault of his own, was unwilling or incapable of providing it at the time. In the absence of any clear indication that there were no weapons involved in the incident, it seems to me that the decision to not assign COAST in this case was a prudent one and in compliance with the policy in effect at the time. In any event, given that Mr. Campbell did in fact have a knife in his possession, it is not clear that COAST could have played much of a role in the incident even had they been initially deployed.

In conclusion, Mr. Campbell’s death was doubtless a tragedy. He was clearly unwell and not of sound mind when he picked up a knife and brandished it at the SO and WO #2. However, as I have no reasonable grounds based on the foregoing analysis to believe the SO acted other than lawfully in his interaction with Mr. Campbell, there is no basis for proceeding with criminal charges in this case, and the file is closed.

Date: December 3, 2020

Electronically approved by

Joseph Martino

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Section 34 of the Criminal Code sets out the circumstances in which conduct that would otherwise constitute an offence is legally justified in defence of oneself or another. It provides that a person may use force to repel a reasonably apprehended attack, actual or threatened, as long as the force is reasonable. The reasonableness of the force in question is to be measured on the basis of the relevant circumstances that prevailed at the time, including such considerations as the nature of the force or threat; the extent to which the use of force was imminent and whether there were other means available to respond to the potential use of force; whether any party to the incident used or threatened to use a weapon; and, the nature and proportionality of the person’s response to the use or threat of force. Upon careful consideration of the evidence collected by the SIU, I am unable to reasonably conclude that the force used by the SO fell outside the ambit of section 34’s protection.

I have little doubt that the SO believed he was acting in self-defence, and perhaps in defence of his partner, WO #2, when he discharged his firearm at Mr. Campbell. The SO did not avail himself of an interview with the SIU, which was his legal right. Of course, that means there is no direct evidence regarding the officer’s mindset at the time of the shooting. Nevertheless, there is nothing in the circumstantial evidence, to be explored below, that would cause me to believe the SO was without a genuine belief that he was acting to protect himself, and plenty in that same body of evidence to strongly suggest that was precisely what he was doing. The real issue, in my view, is whether the SO’s apprehensions, and the shooting they precipitated, were reasonable in the circumstances.

Before turning to the reasonableness analysis, it should be noted that the officers were lawfully present inside the kitchen. They had been called to the home by Mr. Campbell and were let into the house by CW #2. They were duty bound, in the circumstances, to investigate the reported domestic disturbance that had prompted Mr. Campbell’s call and thus were within their rights to follow CW #2 into the kitchen.

There is a strong case to be made that the SO reasonably believed that he needed to fire his gun to protect himself against the imminent risk of a knife attack at the hands of Mr. Campbell. Mr. Campbell had in his possession a dangerous weapon – a knife with a long blade – that could be used to inflict grievous bodily harm or death. By the time of the shooting, the officers had been unable to dispossess Mr. Campbell of the knife despite repeated direction that he drop it, several CEW discharges (one or more of which that might have successfully connected), and a physical struggle on the kitchen floor. It did not appear that Mr. Campbell was about to voluntarily surrender the knife.

It is also likely, in my view, that Mr. Campbell had obtained the knife in order to wield it as a weapon. While there was some evidence that Mr. Campbell simply had the knife in his hands because he was using it to prepare food in the kitchen, the weight of the evidence, including that coming from some members of the Campbell family, suggests that he had retrieved it just before the officers’ entry into the kitchen in order to confront them with it. For example, CW #2 noted that Mr. Campbell was not in the kitchen when she left to answer the officers’ knock on the door. In addition, CW #4 says she overheard her mother asking Mr. Campbell why he had a knife as she (CW #2) and the officers entered the kitchen. This same evidence lends credence to WO #2’s account of the manner in which Mr. Campbell was holding the knife when they first saw him and then again just before he was shot, namely, up by his chest area and pointed toward the officers, albeit it must be acknowledged that there is contrary evidence in this area. Mr. Campbell’s sisters, CW #3 and CW #4, each say that Mr. Campbell’s arms were down by his side just before he was shot.

With respect to whether there were alternatives other than a resort to lethal force, it is arguable whether the officers, confronted by an individual holding a knife, ought to have withdrawn from the kitchen. It is conceivable that a retreat of some extent might have de-escalated the situation and averted a physical and, ultimately, lethal confrontation. Instead, as it turned out, the SO immediately began to yell at Mr. Campbell upon entering the kitchen to drop the knife while pointing a CEW at him, quickly turning the interaction into an armed standoff. On the one hand, the SO and WO #2 had no reason to believe that there had been any violence involving Mr. Campbell and members of his family prior to their arrival and, therefore, some basis to conclude that the balance of risks favoured disengagement. On the other hand, if Mr. Campbell had given no indication of violence ahead of their arrival, the same cannot be said once the officers were in the kitchen. More to the point, Mr. Campbell’s presence in the kitchen with a large knife and steadfast refusal to drop it would have impressed on the officers that he was capable of inflicting harm on them. But not only them, on Mr. Campbell’s family as well; after all, it was Mr. Campbell who had demanded that the police attend his residence to assist in an argument with his parents. I am further satisfied that withdrawal would not have been a simple matter. Given the confined space in which Mr. Campbell and the officers found themselves, it is not readily apparent that the officers had the necessary freedom of movement to safely and successfully remove themselves from the kitchen. In the circumstances, I am unable to dismiss as unreasonable the officers’ decision to stand their ground.

Finally, whether Mr. Campbell moved toward the officers just before he was shot is an important part of the inquiry and also the subject of discrepant accounts in the evidence. CW #3 and CW #4 maintain that their brother was standing in place, not having made any movements toward the officers, when the SO discharged his firearm. In contrast, WO #2 says that Mr. Campbell took one or two deliberate steps forward before he was shot. I am unable to resolve this conflict in the evidence. While there is evidence that CW #3 was not in the kitchen at the time of the shooting, I have no reason to question the veracity of CW #4’s description of her brother’s movements. Similarly, there is nothing in the evidence to cast doubt on the credibility of WO #2’s evidence. Accordingly, I accept that there is some evidence to reasonably conclude that Mr. Campbell had not in fact advanced upon the SO when he was shot. That conclusion, however, is not the end of the analysis.

In the fraught atmosphere that prevailed at the time, it is entirely plausible that a reasonable person in the SO’s shoes would believe that he or she was at immediate risk of a knife attack by Mr. Campbell when the officer discharged his firearm, whether or not Mr. Campbell had taken any steps toward him. The weight of the evidence, for example, establishes that Mr. Campbell was at the very least swaying on his feet when he was shot. It may be that Mr. Campbell was doing so not with any malevolent intention but simply because he had just been “tasered” and was therefore naturally unsteady on his feet. However, the suggestion does not detract from the distinct possibility that Mr. Campbell’s gestures led the SO to reasonably believe that he was on the verge of being attacked.

On the aforementioned-record, I am unable to reasonably conclude with any confidence that the SO acted without legal justification when he shot Mr. Campbell. On the contrary, the evidence suggests that the SO credibly believed at the time that he was confronted with a real and present danger to life and limb, and that his use of force was reasonable in the circumstances. Though faced with an individual wielding a large knife in his direction, the SO did not immediately draw his firearm. Rather, as with his partner, WO #2, the officer pointed his CEW at Mr. Campbell and directed him to drop the knife. It was only after several CEW discharges and a physical struggle on the floor had failed to dispossess Mr. Campbell of the knife that the SO drew his firearm. Whether in the cold light of hindsight it can be said that shooting Mr. Campbell was absolutely necessary in the moment to protect the SO or his partner from an immediate risk of death or grievous bodily arm is arguable. To reiterate, there is evidence that Mr. Campbell had not made any movement to close the distance between him and the officers when the shots were fired. That said, Mr. Campbell was already in close proximity to the SO when the SO discharged his firearm. In the context of what was a highly dynamic and violent confrontation with an individual brandishing a knife, I am satisfied that there is insufficient evidence to reasonably establish that the SO’s gunfire amounted to an unlawful use of force. [5]

This case and others raise important and systemic issues about the manner in which police respond to mental health calls. This was one such call. While en route to Mr. Campbell’s residence, the SO and WO #2 were advised that Mr. Campbell suffered from mental illness, specifically, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. They were also informed that the police had last been to the address in February 2019 as Mr. Campbell had not been taking his medication and was being aggressive with family members.

The SIU’s statutory mandate, however, is a narrow one. It is to determine whether there are reasonable grounds to believe that a criminal offence has been committed by applying the law as it stands to the facts as they are discerned, not to delve into broader public policy considerations that may be implicated in any particular case. There are other bodies with the institutional mandates and competence to conduct those reviews. This does not mean that questions of mental health that are raised in the specific circumstances of an incident are not relevant in a criminal investigation; of course, they may well be. It does mean that care must be taken to ensure that the inquiry remains focused on the conduct of the individuals, not the merits or failings of the system within which they operate.

In the instant case, the conduct of the SO and WO #2 in the lead-up to the encounter with Mr. Campbell is in some ways subject to legitimate criticism. Though they knew that Mr. Campbell suffered from mental illness and was likely in an agitated condition, they did not confer with each other about the approach they would take once inside the home. Thus, there was no talk of how they would react in the face of various contingencies, such as who between them would take the lead in dealing with Mr. Campbell or how de-escalation might be pursued should the need present itself. Whether those conversations would have made a difference to the outcome is speculation, but the officers’ failure to have that discussion limited their ability to consider alternative strategies. Moreover, once in the kitchen, the SO immediately began to order Mr. Campbell to put the knife down. At no point was there any effort made to verbally calm Mr. Campbell.

The offence that arises for consideration in light of this conduct is criminal negligence causing death contrary to section 220 of the Criminal Code. The offence is predicated, in part, on conduct that constitutes a marked and substantial departure from the level of care that a reasonable person would have exercised in the circumstances. In my view, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the officers transgressed the limits of care prescribed by the criminal law in the moments before their standoff with Mr. Campbell. Thus, while the officers perhaps should have done more to take stock of the situation before they knocked on the door, it is not as if the officers entered the home without some appreciation of what they might encounter. WO #2, for example, says she was cognizant of the fact there were no sounds of a disturbance coming from the house as they knocked on the front door. Once through the door, there were also no signs of trouble in the household. CW #2 confirmed that there had been an argument involving Mr. Campbell and that he suffered from mental illness, but otherwise everything appeared calm. Finally, with respect to the tact adopted by the officers upon seeing Mr. Campbell, their failure to meaningfully engage in any efforts to talk Mr. Campbell down is tempered by the fact that they were being confronted by an individual pointing a knife in their direction. On this record, if there were lapses in judgment on the part of WO #2 or the SO, they were neither reckless nor wanton in the circumstances.

There remains the question of the potential deployment of the PRP Crisis Outreach Assessment Support Team, or COAST. Each COAST unit pairs a plainclothes officer with a mental health professional, who are available to respond to calls on a 24-7 basis. COAST is a method by which the police service seeks to respond more effectively to calls for service involving persons experiencing mental health crisis or emotional distress. However, pursuant to the PRP policy in effect at the time, COAST units are not mobilized unless the following four conditions are met: the call involves someone 16 years of age and over who is experiencing a mental health issue; the call is not of an emergent nature; there are no weapons involved in the call; and, the situation is calm.

I am unable to find fault with the decision not to deploy the COAST team in response to Mr. Campbell’s 911 call to police. The police call-takers, who are responsible for deciding whether or not COAST involvement is appropriate, are tasked with gathering information from the caller with which to make the assessment. These inquiries include whether the person experiencing crisis is armed or has access to weapons. The call-taker who took Mr. Campbell’s call, however, was unable to obtain this information as Mr. Campbell, perhaps through no fault of his own, was unwilling or incapable of providing it at the time. In the absence of any clear indication that there were no weapons involved in the incident, it seems to me that the decision to not assign COAST in this case was a prudent one and in compliance with the policy in effect at the time. In any event, given that Mr. Campbell did in fact have a knife in his possession, it is not clear that COAST could have played much of a role in the incident even had they been initially deployed.

In conclusion, Mr. Campbell’s death was doubtless a tragedy. He was clearly unwell and not of sound mind when he picked up a knife and brandished it at the SO and WO #2. However, as I have no reasonable grounds based on the foregoing analysis to believe the SO acted other than lawfully in his interaction with Mr. Campbell, there is no basis for proceeding with criminal charges in this case, and the file is closed.

Date: December 3, 2020

Electronically approved by

Joseph Martino

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Endnotes

- 1) The times are those produced by the internal clock of the devices, and not necessarily synchronized precisely with actual time. [Back to text]

- 2) Firearm discharge residues will become broader and less concentrated the further they travel from the muzzle until no residues are deposited on a surface. Typically, soot is not observed at distances greater than 12 inches and propellant is typically not observed at distances greater than 36 inches. Different types and combinations of ammunition and firearms will result in different types, amounts and patterns of deposits on an item. [Back to text]

- 3) Tracks 21 and following relate to transmissions that occur prior to the first 20 tracks. [Back to text]

- 4) If the call-taker determines that the situation only warrants assistance from a community agency, the call-taker is required to request authority from the communications supervisor to refer the caller to an approved agency with the communications centre. [Back to text]

- 5) As I am satisfied that the SO’s decision to discharge his firearm was justified pursuant to section 34 of the Criminal Code, I am also satisfied that the lesser force he used in an unsuccessful effort to remove the knife from Mr. Campbell’s possession, namely, the CEW discharges and physical force that preceded the shooting, were also legally justified. [Back to text]

Note:

The signed English original report is authoritative, and any discrepancy between that report and the French and English online versions should be resolved in favour of the original English report.