SIU Director’s Report - Case # 17-TVI-104

Warning:

This page contains graphic content that can shock, offend and upset.

Contents:

Mandate of the SIU

The Special Investigations Unit is a civilian law enforcement agency that investigates incidents involving police officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The Unit’s jurisdiction covers more than 50 municipal, regional and provincial police services across Ontario.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Information restrictions

Freedom of Information and Protection of Personal Privacy Act (“FIPPAâ€)

Pursuant to section 14 of FIPPA (i.e., law enforcement), certain information may not be included in this report. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- Confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by law enforcement agencies; and

- Information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding.

Pursuant to section 21 of FIPPA (i.e., personal privacy), protected personal information is not included in this document. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- subject officer name(s)

- witness officer name(s)

- civilian witness name(s)

- location information

- witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence and

- other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation

Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 (“PHIPAâ€)

Pursuant to PHIPA, any information related to the personal health of identifiable individuals is not included.

Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from this report because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner’s inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.

Mandate engaged

The Unit’s investigative jurisdiction is limited to those incidents where there is a serious injury (including sexual assault allegations) or death in cases involving the police.

“Serious injuries†shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury†shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the serious injury reportedly sustained by a 25-year-old man during a motor vehicle accident on May 5, 2017.

The investigation

Notification of the SIU

On May 5, 2017, at 3:50 a.m., the Toronto Police Service (TPS) notified the SIU of a vehicle injury that occurred around 2:00 a.m. that morning.

The TPS reported that the Subject Officer (SO) and Witness Officer (WO)Â #1 assigned to the Public Safety Response Team (PSRT) saw a vehicle travelling at a high rate of speed on Weston Road. They broadcast their observation to other units before coming across the vehicle at 115 King Street[1] after it had collided with a tree.

The driver fled the scene and the injured passenger was taken to the hospital with a fractured leg.

Shortly after the collision, a female called the police to report her vehicle had been stolen. This was the same vehicle involved in the collision.

The scene was secured and the involved police officers were segregated at a TPS Division station.

The team

Number of SIU Investigators assigned: 6

Number of SIU Forensic Investigators assigned: 3

Number of SIU Collision Reconstructionists assigned: 1

SIU Forensic Investigators responded to the scene and identified and preserved evidence. They documented the relevant scenes associated with the incident by way of notes, photography, videography, sketches and measurements.

Complainant

25-year-old male interviewed, medical records obtained and reviewed

Civilian witnesses

None

Witness officers

WOÂ #1 Interviewed

WOÂ #2 Interviewed

WOÂ #3 Interviewed

Subject officers

SO Interviewed, and notes received and reviewed.

Incident narrative

During the early morning hours of May 5, 2017, the Complainant was the passenger in a stolen Ford SUV. The SO and WO #1 initially saw the Ford turn left onto northbound Weston Road from Little Avenue, a side street on the west side of Weston Road. The SUV was driving at a high rate of speed, and the SO followed the Ford along King Street as it drove north a short distance then turned right onto King Street and drove east.

The driver of the Ford lost control at the curve along King Street, and the motor vehicle mounted the curb and crashed into a large tree on the front lawn of 116 King Street.

The driver reportedly fled the scene before the SO and WO #1 arrived, and the Complainant was located outside the Ford. Because of the accident and the Complainant’s obvious injuries, an ambulance was called and attended the scene. The Complainant was transported to hospital and diagnosed with fractures of his left tibia, fibula and ankle as well as to his left hand. He also sustained a fracture to the fifth digit of his right hand and lacerations to the tendons of the fourth and fifth digits of his right hand.

Evidence

The scene

At the scene of the accident, King Street is a two-lane, two-way, asphalt-paved road in a residential area with concrete curbs and sidewalks on both sides of the street. The posted speed limit is 30Â km/h.

At the intersection with Elm Street, King Street realigns where eastbound traffic has to turn left and then right to continue along the road.

Just east of the intersection of King and Elm Streets, the Ford crossed the centre line and into the westbound lane of the road. It mounted the north curb and drove across the grass boulevard of the home at 114 King Street. It then crossed the sidewalk and drove across the lawn of the home at 116 King Street, where it collided into a large tree on the front lawn.

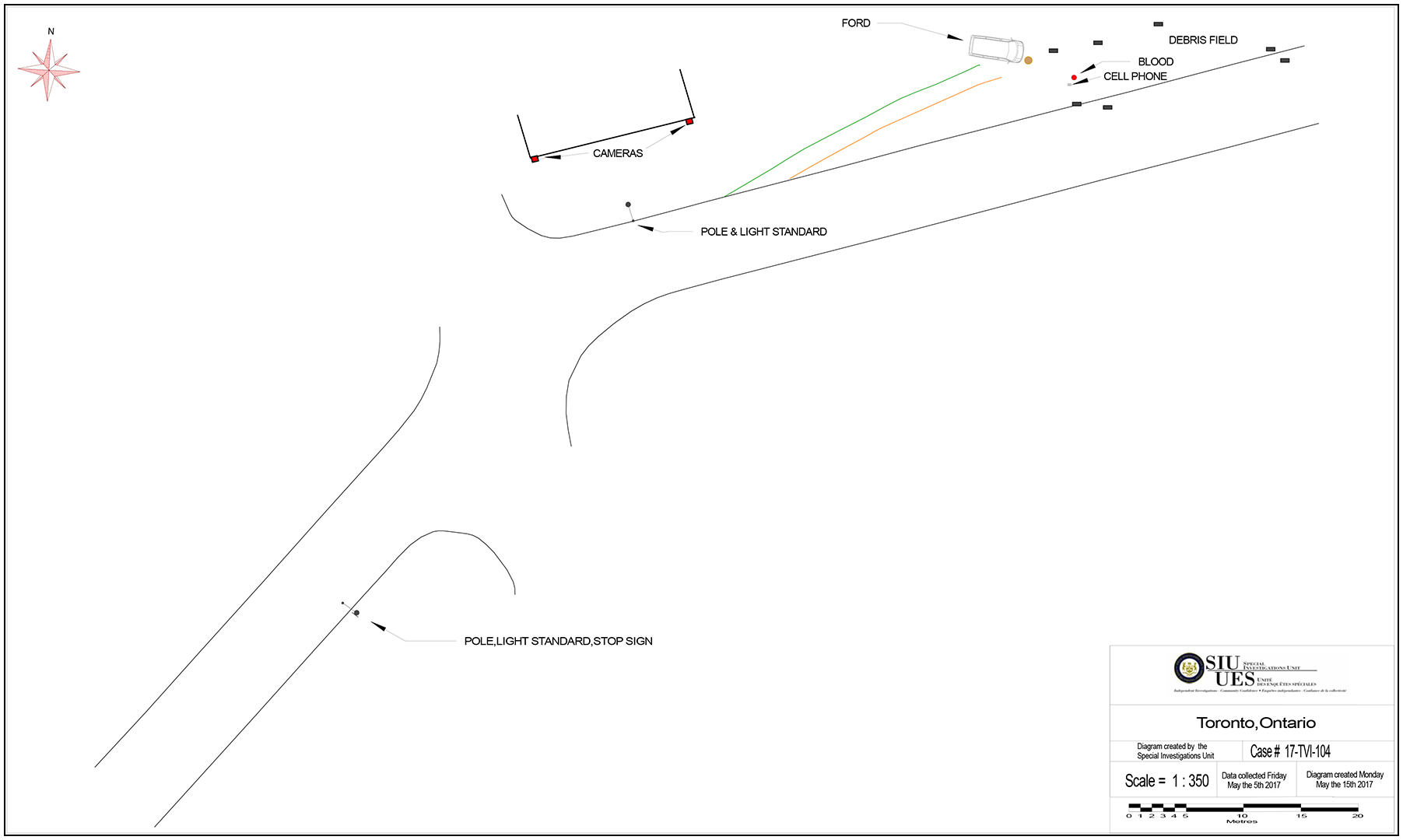

Scene diagram

Physical evidence

Involved vehicles

Ford SUV

The involved civilian vehicle is a Ford SUV, owned by Enterprise Rental. The vehicle sustained extensive front end damage with intrusion into the passenger compartment.

Download of the Crash Data Retrieval module revealed the vehicle was driving at 129Â km/h, five seconds before the collision. The brakes were applied three seconds before the collision, while the vehicle was moving at 124Â km/h. It continued to slow and collided with the tree at 68Â km/h.

TPS Cruiser

The involved cruiser was a fully marked Ford Crown Victoria. The cruiser was a “spare car,†an older fleet vehicle that was being phased out of circulation, and as such had no in-car-camera-system (ICCS) recording equipment.

The cruiser was examined on the day this incident occurred and showed no evidence of contact with the involved Ford. The emergency equipment was observed in proper working order.

Automated Vehicle Locator (AVL) Data

The AVL download revealed that the cruiser reached a speed of 76Â km/h on King Street. Although there were two stop sign controlled intersections along the route, the data recorded a slowest speed of 47Â km/h.

The following screenshot from Google Earth depicts the locations of the cruiser and the AVL marked points leading to the collision scene.

As the cruiser neared the collision scene, AVL data only captured the speed at 69Â km/h at 1:47:44Â a.m. as it approached the intersection with Elm Street. The next data point captured was 18Â seconds later, where the cruiser was already stopped at the collision scene.

Expert evidence

Collision reconstruction

The collision reconstruction investigation revealed that four seconds prior to the collision, the Ford was driving at 128Â km/h and the brakes had not been applied. Time/distance calculations indicated that it was at that time that the vehicle drove through the stop sign controlled intersection at Elm Street.

After failing to negotiate the realignment of King Street, the driver lost control of the vehicle. The brakes were applied three seconds before impact, as the vehicle mounted the curb and slowed to 68Â km/h, when it collided violently with a large tree.

Video/audio/photographic evidence

The SIU canvassed the area for any video or audio recordings, and photographic evidence and received closed circuit television (CCTV) video recordings from five addresses on King Street, along the route travelled by the involved vehicles.

The five sources of video recordings obtained by the SIU will be detailed in this report from west to east, as the vehicles drove along King Street.

- 15 King Street

At 12:57:08Â a.m. on the video recording, a dark four door SUV, believed to be the Ford, turned right and drove east on King Street from Weston Road. A fully marked TPS cruiser with no emergency lighting activated drove the same route about seven seconds later.

- 30 King Street

At 1:47:07Â a.m. on the video recording, a dark four door SUV drove east on King Street. A fully marked TPS cruiser with no emergency lighting activated drove the same route about eight seconds later.

- 31 King Street

At 1:46:42Â a.m. on the video recording, a dark four door SUV drove east on King Street. A fully marked TPS cruiser with no emergency lighting activated drove the same route about eight seconds later.

- 38 King Street

At 12:58:25Â a.m. on the video recording, a dark four door SUV drove east on King Street. A fully marked TPS cruiser with no emergency lighting activated drove the same route about 11Â seconds later.

- 108 King Street

Three of the four cameras mounted in various directions outside the address captured the Ford approaching from the west at what appeared to be a high rate of speed. The time stamp on the recordings was about 11Â hours and 56Â minutes ahead of the correct time [Eastern Standard Time (EST)].

Camera 2 was aligned to view the north sidewalk on King Street, facing west, toward Weston Road. At 1:47:12 p.m. on the recording, the Ford’s headlights were initially visible as it approached. Seven seconds later, the vehicle entered the intersection of King Street at Elm Street at a high rate of speed. Five seconds later, at 1:47:24 p.m. on the recording, the cruiser’s headlights initially became visible in the vicinity of Rosemount Avenue. The cruiser entered the intersection at Elm Street without stopping at 1:47:41 p.m. on the recording, about 22 seconds after the Ford.

Camera 3 was aligned to view the east sidewalk on Elm Street, facing generally south, toward King Street. This camera also captured images of the Ford driving through the intersection at Elm Street, disobeying the stop sign, at a high rate of speed. The cruiser travelled the same direction about 21Â seconds later, with no emergency lighting activated.

Camera 1 was aligned to view the north sidewalk on King Street, facing east. The camera captured the Ford entering view at 1:47:20 p.m. on the recording. About one second later, the brake lights activated for about one second. Dust and debris were then seen. A fully marked TPS cruiser with no emergency lighting activated then approached from the east and drove past the camera’s view at a much slower speed.

Communications recordings

Although the SIU investigators were initially told the PSRT police officers were broadcasting on a frequency that is not recorded, the SO told the SIU investigators that they were using the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) PATH 6 channel, which is typically used by the TPS in the TTC and underground PATH system in downtown Toronto. The frequency is in fact recorded.

In the initial recording on TTC PATH 6, a police officer, now known to be WO #3, directed the team to “head back to the station.†In a later transmission, a police officer reported, “Yea 12. We just had an SUV take off on us. King Drive eastbound at Rosemount.†WO #3 responded, “Get it on the divisional band please.â€

WO #1 then reported, “I think we’re at 115 King Drive. Crashed out on the lawn here.†WO #3 advised, “Make sure you put it over the main band.â€

On the TPS Division band, WO #1 reported, “It looks like we got a vehicle crashed out in front of one fifteen. I think it’s King Street here†and requested that an ambulance attend.

Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) report

The CAD report noted that police officers reported a collision at 1:49Â a.m.

About a minute later, they reported one individual, possibly the driver, was on scene but it appeared that two people were in the vehicle, as both airbags had deployed and there was blood on both air bags.

Materials obtained from Police Service

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the TPS:

- Communications recordings

- Scene photos

- Global Positioning System (GPS) / AVL Data and Table

- Event Details Reports

- General Occurrence Reports

- Major Crime Scene Log

- Motor Vehicle Collision Report

- Notes of WOÂ #1, WOÂ #2 and WOÂ #3

- Procedure - Suspect Apprehension Pursuit

- Automated Dispatch System (ADS) Summary Sheets - Summary of Conversations, and

- Unit History Report

Relevant legislation

Sections 1-3, Ontario Regulation 266/10, Ontario Police Services Act – Suspect Apprehension Pursuits

- (1) For the purposes of this Regulation, a suspect apprehension pursuit occurs when a police officer attempts to direct the driver of a motor vehicle to stop, the driver refuses to obey the officer and the officer pursues in a motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle or identifying the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle.

(2) A suspect apprehension pursuit is discontinued when police officers are no longer pursuing a fleeing motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle or identifying the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle.

- (1) A police officer may pursue, or continue to pursue, a fleeing motor vehicle that fails to stop,

- if the police officer has reason to believe that a criminal offence has been committed or is about to be committed; or

- for the purposes of motor vehicle identification or the identification of an individual in the vehicle.

(2) Before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall determine that there are no alternatives available as set out in the written procedures of,

- the police force of the officer established under subsection 6 (1), if the officer is a member of an Ontario police force as defined in the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009;

- a police force whose local commander was notified of the appointment of the officer under subsection 6 (1) of the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, if the officer was appointed under Part II of that Act; or

- the local police force of the local commander who appointed the officer under subsection 15 (1) of the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, if the officer was appointed under Part III of that Act.

(3) A police officer shall, before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, determine whether in order to protect public safety the immediate need to apprehend an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle or the need to identify the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle outweighs the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit.

(4) During a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall continually reassess the determination made under subsection (3) and shall discontinue the pursuit when the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit outweighs the risk to public safety that may result if an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not immediately apprehended or if the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not identified.

(5) No police officer shall initiate a suspect apprehension pursuit for a non-criminal offence if the identity of an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is known.

(6) A police officer engaging in a suspect apprehension pursuit for a non-criminal offence shall discontinue the pursuit once the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is identified.

- (1) A police officer shall notify a dispatcher when the officer initiates a suspect apprehension pursuit.

(2) The dispatcher shall notify a communications supervisor or road supervisor, if a supervisor is available, that a suspect apprehension pursuit has been initiated.

Sections 219 and 221, Criminal Code - Criminal negligence

219 (1) Every one is criminally negligent who

- in doing anything, or

- in omitting to do anything that it is his duty to do,

shows wanton or reckless disregard for the lives or safety of other persons.

(2) For the purposes of this section, duty means a duty imposed by law.

221 Every one who by criminal negligence causes bodily harm to another person is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years.

Section 249, Criminal Code - Dangerous operation of motor vehicles, vessels and aircraft

- Every one commits an offence who operates

- a motor vehicle in a manner that is dangerous to the public, having regard to all the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that at the time is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place…

(3) Every one who commits an offence under subsection (1) and thereby causes bodily harm to any other person is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years.

Analysis and Director’s decision

On May 5th, 2017 at approximately 1:45 a.m., Toronto Police Service (TPS) officers with the PSRT were directed by WO #3 to “head back to the station†following an exercise. Shortly thereafter, and while en route back to the TPS Division, the SO and WO #1 observed a motor vehicle travelling at a high rate of speed and communicated over the radio “We just had a SUV take off on us, King Drive eastbound at Rosemount†whereupon they were directed by WO #3 to report the facts on the Divisional Band channel, as they had been using the TTC band up until that point. At 1:49:34 a.m., WO #1 is heard to report “115 King Road, crashed out on the lawn here†and again WO #3 is heard to direct “make sure you put it on the main bandâ€. Upon arriving at the accident scene at 116 King Street, the SUV was located having collided with a tree and having sustained extensive damage. The Complainant was located outside of the car, on the ground, and claimed to have been the passenger in the motor vehicle. No second party was located, but both airbags had been deployed and both had blood on them, confirming that two parties had been in the motor vehicle at the time of the crash. The Complainant was transported to hospital where he was diagnosed with having sustained fractures of his left tibia, fibula, ankle, left hand, and the fifth digit of his right hand. He also sustained lacerations to the tendons in his right hand. The SUV, a Ford, was later discovered to have been stolen earlier that day.

During the course of this investigation, the only civilian witness to the interaction with police, the Complainant, was interviewed. There were unfortunately no other civilians who observed either the pursuit or the ultimate collision. Both the SO and WOÂ #1 were interviewed and provided their memorandum book notes for review. No other police witnesses observed the interaction. SIU investigators, however, also had access to the data from both the police cruiser and the Ford, the communications recordings, the accident reconstruction report and the CCTV footage from various premises along the route taken by the Ford and the police cruiser. All of these various pieces of evidence together allowed for a fairly clear picture of what occurred to be pieced together.

According to the AVL data from the police vehicle operated by the SO, the cruiser reached speeds of 76Â km/h on King Street and apparently ran two stop signs without stopping, with its lowest speed being 47Â km/h. The posted speed limit on King Street was 30Â km/h.

The Crash Data Retrieval module data from the Ford revealed that it was travelling at 129Â km/h five seconds prior to impact, and the brakes were applied three seconds prior to impact, when the vehicle was travelling at 124Â km/h and that the vehicle slowed, as a result of the depression of the brakes, to 68Â km/h at the time of impact.

Various CCTV recordings obtained from premises on the route taken by the Ford and the police cruiser operated by the SO revealed that in the area of 15 King Street, the Ford turned right onto King Street from Weston Road and was followed by a fully marked police cruiser without any emergency lighting activated and some seven seconds behind. At 30 King Street, the police cruiser is seen to be eight seconds behind the Ford - it still has not activated its emergency lighting. At 38 King Street, the police cruiser is now 11Â seconds behind, while at 108 King Street the Ford is seen travelling at a high rate of speed and then entering the intersection of King Street and Elm Street, and five seconds later the headlights of the cruiser are seen to approach. The Ford is then seen to activate its brake lights and dust and debris are seen, presumably indicative of the impact. The cruiser is seen 21Â seconds later, now operating at a much slower rate of speed, driving through that same intersection. On all of the recordings, at no time is the marked police cruiser seen with its emergency lighting system activated.

There is no dispute, and as is confirmed both by the Complainant, the CCTV recordings and upon examination of the police cruiser, that at no time was there any contact between the police cruiser and the Ford.

On a review of all of the evidence, I have no difficulty in concluding that the police vehicle operated by the SO was involved in a police pursuit with the motor vehicle in which the Complainant was an occupant and that he was in breach of the Ontario Police Service Act (OPSA) legislation, as well as the companion TPS Regulation - entitled “Suspect Apprehension Pursuit†for the following reasons:

Pursuant to Ontario Regulation 266/10 of the OPSA entitled Suspect Apprehension Pursuits

s2(1) A police officer may pursue, or continue to pursue, a fleeing motor vehicle that fails to stop,

- If the police officer has reason to believe that a criminal offence has been committed or is about to be committed; or

- For the purposes of motor vehicle identification or the identification of an individual in the vehicle.

(2) Before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall determine that there are no alternatives available ….

(3) A police officer shall, before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, determine whether in order to protect public safety the immediate need to apprehend an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle or the need to identify the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle outweighs the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit.

(4) During a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall continually reassess the determination made under subsection (3) and shall discontinue the pursuit when the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit outweighs the risk to public safety that may result if an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not immediately apprehended or if the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not identified.

The TPS Policy put in place pursuant to the OPSA legislation, reads as follows:

Responsibility for Safe Conduct

The responsibility for the safe conduct of a pursuit rests with the individual police officer, the Communications Operator – Communications Services, the pursuit supervisor and any other authorized person monitoring the pursuit.

Where, as here, the officer initiating the pursuit never advised the Communications Operator about the pursuit, it of course cuts out the involvement of “the Communications Operator, the pursuit supervisor and any other authorized person monitoring the pursuitâ€, since it is clear that no one would then monitor the pursuit. Despite the direction from WO #3 to “Get it on the Divisional band, please†as soon as WO #1 reported that “We just had a SUV take off on us†at 1:47:23 a.m., the Divisional band is not in fact notified until after the crash is reported at 1:49:34 a.m., over two minutes later.

On the evidence it is clear that the SO observed a speeding motorist and decided to follow it and investigate, which he presumably would have done by initiating a traffic stop. At no time did he have any grounds to believe that a criminal offence had been committed, but rather he was dealing with a speeding infraction under the Highway Traffic Act. Furthermore, despite the indication that the Ford was travelling at a high rate of speed and made an abrupt right turn from Weston Road onto King Street, there is no indication from the SO or WO #1 as to what that “high rate of speed†actually was. Additionally, the weather conditions were poor, the roads were wet, and the pursuit took place in a residential area where the posted speed limit was only 30 km/h. The SO’s evidence, wherein he indicated that he stopped at the stop sign at Elm Street, is contradicted by the CCTV footage as well as the AVL data, which revealed that at no time did the SO stop for any of the stop signs on King Street.

With respect to WO #1’s contention that he and the SO did not activate their emergency lighting because “we were going homeâ€, it is clear that they were not “going home†as they had decided to follow and pursue the Ford instead. Even were they “going homeâ€, that would not justify not activating their emergency lighting equipment when engaged in a pursuit in a residential area at speeds more than two times the posted limit. Additionally, WO #1’s response of “There was no pursuit to call in†when asked by SIU investigators whether or not he called in the pursuit, appears to me to be quite inane. It is clear on all of the evidence that the SO pursued the Ford from the intersection of Weston Road and King Street until the intersection of Elm and King Streets, a distance of some 650 metres, where he observed that the vehicle had collided with a tree, and at no time did either officer contact the communications centre to advise that he was involved in a pursuit, despite the fact that the SO had been pursuing the Ford vehicle on King Street at a rate of speed of up to 76 km/h in a 30 km/h residential zone. Semantics aside, there can be no confusion that a cruiser travelling at that rate of speed (in a 30 km/h zone), following a motor vehicle, is clearly in pursuit. The SO and WO #1 had an obligation to report to the dispatcher that they were engaged in a pursuit as soon as it was initiated and to say that there simply was no pursuit is to distort the meaning of the legislation. WO #1, who was not driving, had every opportunity to advise dispatch of what was occuring, but he did not make his initial contact with dispatch until after the collision had already occurred. I cannot imagine that any reasonable person would believe that issuing a speeding ticket would have outweighed the risk to public safety of continuing to pursue a motor vehicle at the speeds which the SO did, in those weather and road conditions, and in a posted 30 km/h zone.

The words “pursuit†or “I am not attempting to stop†are not magical words that somehow transform what is obviously a pursuit into something else which somehow avoids the obligations on police pursuant to the Suspect Apprehension Pursuits legislation. Pursuant to this legislation, “a suspect apprehension pursuit occurs when a police officer attempts to direct the driver of a motor vehicle to stop, the driver refuses to obey the officer and the officer pursues in a motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicleâ€. Although the SO claimed that he wished to investigate the vehicle, I can see no reason to follow/chase a vehicle at more than twice the posted speed limit for any other purpose than to attempt to stop it. Once WO #1 advised WO #3 that “We just had an SUV take off on usâ€, he should have switched to the divisional band, as directed by WO #3, and made them aware that the vehicle had just taken off and those words should have been immediately followed by “We are now in pursuit and travelling at 76 km/hâ€, in order that the communication sergeant would have been in a position to make the decision as to whether or not the pursuit should have been terminated.

Additionally, I note that the evidence of the Complainant is far more consistent with both the AVL data and the CCTV footage, than it is with the evidence of the SO and WOÂ #1 that they had in fact lost sight of the Ford prior to the collision. On all of this evidence, I have no difficulty finding that the SO and WOÂ #1 were in fact in pursuit of the Ford and were in contravention of not only Ontario Regulation 266/10 of the OPSA entitled Suspect Apprehension Pursuits, but also the companion TPS legislation, not only by failing to advise dispatch of the pursuit, but also by failing to activate the emergency lighting system, and by failing to take into consideration whether or not the pursuit outweighed the risks to public safety. It was very fortunate, due to the time of night, that there was no other vehicular traffic and no pedestrians, or the outcome of this matter could have been much worse, if not fatal.

Having said all of that, however, a failure to comply with the OPSA or the TPS policy does not equate with reasonable grounds to believe that a criminal offence has been committed.

The question to be determined is whether or not there are reasonable grounds to believe that the SO committed a criminal offence in his pursuit of the Ford, specifically whether or not the driving rose to the level of being dangerous and therefore in contravention of s.249(1) of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm contrary to s.249(3), or if it amounted to criminal negligence contrary to s.221 of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm. The decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Beatty, [2008] 1 S.C.R. 49, sets out the elements of the offence of dangerous driving under s. 249 and found that it requires that the driving be dangerous to the public, having regard to all of the circumstances, including “the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that, at the time, is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place†and the driving must be such that it amounts to “a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the accused’s circumstancesâ€. While the offence under s.221 requires “a marked and substantial departure from the standard of a reasonable driver in circumstances†where the accused “showed a reckless disregard for the lives and safety of others†(R. v. Sharp (1984), 12 C.C.C. (3d) 428 (Ont. CA)).

On a review of all of the evidence, it is clear that the SO was travelling at excessive rates of speed (given it was a residential area) when pursuing the Ford motor vehicle while disregarding various stop signs. I find, however, that there is no evidence that the driving created a danger to other users of the roadway or that at any time they interfered with other traffic, in that fortunately there was no other traffic, either vehicular or pedestrian, at that time of night. The officer’s significant rate of speed in his pursuit of the Ford motor vehicle, however, appeared to exacerbate the driver’s pattern of driving, according to the Complainant, apparently causing him to accelerate to ever greater speeds to avoid police. Ultimately, however, I find that the driver of the Ford unfortunately chose to try to outrun police and, in doing so, he fled at a reckless rate of speed and carried out dangerous maneuvers with no regard for other people using the road.

In sum, I find on this evidence that the driving of the SO, while involved in the pursuit and attempt to investigate the Ford, does not rise to the level of driving required to constitute “a marked departure from the norm†and even less so “a marked and substantial departure from the norm†and I am unable to establish that there was a causal connection between the actions of the pursuing officers and the motor vehicle collision that caused the Complainant’s injury. As such, I find that there is insufficient evidence to form reasonable grounds to believe that a criminal offence has been committed and no basis for proceeding with charges in this case.

Date: February 27, 2018

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Endnotes

- 1) [1] The collision actually occurred at 116 King Street. [Back to text]

Note:

The signed English original report is authoritative, and any discrepancy between that report and the French and English online versions should be resolved in favour of the original English report.