SIU Director’s Report - Case # 17-OFD-313

Warning:

This page contains graphic content that can shock, offend and upset.

Contents:

Mandate of the SIU

The Special Investigations Unit is a civilian law enforcement agency that investigates incidents involving police officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The Unit's jurisdiction covers more than 50 municipal, regional and provincial police services across Ontario.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Information restrictions

Freedom of Information and Protection of Personal Privacy Act ("FIPPA")

Pursuant to section 14 of FIPPA (i.e., law enforcement), certain information may not be included in this report. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- Confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by law enforcement agencies; and

- Information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding.

Pursuant to section 21 of FIPPA (i.e., personal privacy), protected personal information is not included in this document. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- subject officer name(s)

- witness officer name(s)

- civilian witness name(s)

- location information

- witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence and

- other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation

Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 ("PHIPA")

Pursuant to PHIPA, any information related to the personal health of identifiable individuals is not included.

Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from this report because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner's inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.

Mandate engaged

The Unit's investigative jurisdiction is limited to those incidents where there is a serious injury (including sexual assault allegations) or death in cases involving the police.

"Serious injuries" shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. "Serious Injury" shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU's investigation into the shooting death of a 70-year-old man (the Complainant) by the police on October 27, 2017.

The investigation

Notification of the SIU

At approximately 12:55 a.m. on October 28, 2017, the Cobourg Police Service (CPS) notified the SIU of the fatal gunshot injuries to the 70-year-old Complainant during his encounter with police officers inside the Northumberland Hills Hospital (NHH) an hour earlier.

The CPS reported that at 11:08 p.m. on October 27, 2017, police were called to the NHH by nursing staff in response to the sound of a gunshot and an utterance by a man that his wife had shot herself in a triage room. Responding police officers were confronted by a man with a firearm in the emergency department. The police officers fired a volley of shots at the man, who died immediately. The man was identified as the husband of the deceased woman.

The Team

Number of SIU Investigators assigned: 6

Number of SIU Forensic Investigators assigned: 3

At 2:00 a.m., on October 28, 2017, six SIU investigators and three SIU forensic investigators (FI) initiated an investigation in Cobourg.

The scene at the NHH was sufficiently secured by the SIU FIs and arrangements were made with senior hospital administrators to keep the Emergency Room area open for patients without interfering with the integrity of the criminal investigation.

The numerous nursing staff and other hospital employee witnesses were interviewed on site. SIU investigators met with OPP investigative staff who were tasked with investigating the death of CW #12. Physical evidence was seized and cataloged and a diagram of the scene was prepared. Eventually, 142 exhibits were collected, a number of which were submitted to the Centre of Forensic Sciences (CFS) for analysis.

On October 30, 2017, SIU investigators arrived at the Forensic Pathology Unit in Toronto to photograph the post-mortem examination of the Complainant, as directed by the attending pathologist.

Photographs of the deceased's clothing and the deceased were taken, and the SIU received the deceased's clothing along with a number of recovered projectiles and fragments; all were individually sealed. The post-mortem was to be continued the following day.

On October 31, 2017, at 9:30 a.m., the post-mortem examination re-commenced, with further photographs taken and exhibits and biological samples collected for submission to the CFS for forensic analysis. The Complainant was also fingerprinted at the conclusion of the examination by SIU FIs.

Complainant:

70-year-old male, deceased

Civilian Witnesses

CW #1 Interviewed

CW #2 Interviewed

CW #3 Interviewed

CW #4 Interviewed

CW #5 Interviewed

CW #6 Interviewed

CW #7 Interviewed

CW #8 Interviewed

CW #9 Interviewed

CW #10 Interviewed

CW #11 Interviewed

CW #12 Not Interviewed - Deceased

CW #13 Interviewed

CW #14 Interviewed

CW #15 Interviewed

CW #16 Interviewed

CW #17 Interviewed

CW #18 Interviewed

CW #19 Interviewed

CW #20 Interviewed

CW #21 Interviewed

CW #22 Interviewed

CW #23 Interviewed

CW #24 Interviewed

Witness Officers

WO #1 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #2 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

Subject Officers

SO #1 Declined interview and to provide notes, as is the subject official's legal right.

SO #2 Interviewed, but declined to submit notes, as is the subject official's legal right.

Incident narrative

On October 27, 2017, CW #12 called the health care worker assigned to herself and her husband, the Complainant, because she was concerned about the Complainant's recent obsession with taking his own life and she was concerned for both his safety and her own.

Upon arrival of the healthcare worker, she spent some time with the Complainant and CW #12, during which the Complainant made several comments which appeared to underscore CW #12's concern that the Complainant intended to take his own life. As a result, the healthcare worker contacted an ambulance to have both the Complainant and CW #12 taken to hospital to address the concerns of CW #12, as well as the ongoing medical issues for both parties. Prior to leaving for the hospital, the Complainant indicated that he needed a moment to get ready, whereupon he went to his room where he was alone for approximately two minutes, following which he re-emerged and the paramedics arrived. As the Complainant was placed on the stretcher by paramedics, he commented to his wife that "It's been a great 46 years of knowing you, I love you, but apparently 47 years wasn't in the cards for us," and indicated to the healthcare worker that they had to "cash the chips in eventually". Both the Complainant and his wife were then transported to hospital.

Once at the hospital, both the Complainant and CW #12 were placed in Triage Room #7 and were left alone until a doctor could see them. Shortly thereafter, a loud bang was heard coming from room 3 and, upon inspection, a nurse noted that CW #12 had been shot in the right side of her head. The Complainant commented to the nurse that CW #12 had shot herself.

CW #12 was immediately taken to the recovery room in attempts to save her life, and 911 was called to obtain the assistance of police.

SO #1 and SO #2 arrived at the hospital and were advised by medical staff that despite the indication from the Complainant that CW #12 had shot herself, they were unable to locate the firearm. SO #1 and SO #2, along with a member of the nursing staff, then attended to Triage Room #7. Upon their arrival, the Complainant pointed a firearm at the two police officers, following which the nurse immediately backed out of the room. The police officers each drew their service firearm and made several demands for the Complainant to put down the weapon; the Complainant did not comply, after which both police officers shot at the Complainant. After the first volley of shots, the officers observed that the Complainant was still moving underneath the blanket and they were unable to see the firearm, as a result of which a second volley of shots was discharged, following which the officers moved in and located and removed the firearm.

The two subject officers discharged their firearms for a combined total of 30 times.

Both the Complainant and his wife, CW #12, were pronounced dead at the scene.

Cause of Death

On October 31, 2017, a post-mortem examination was held at the Forensic Pathology Unit in the City of Toronto during which a number of projectiles and fragments were recovered. The final post-mortem report was received by the SIU on September 13, 2018 and confirmed that the Complainant's cause of death was multiple gunshot wounds. The gunshot wounds were to the torso and extremities, including to the index finger of his right hand and the ring and baby finger of his left hand. The gunshot wounds to the torso were fatal.

The cause of death for CW #12 was determined to be as a result of a single penetrating gunshot wound perforating the brain. The projectile traveled right to left coming to rest on the inside of the left side of her head. The distance estimation was stated as medium and the projectile was recovered.

Evidence

The Scene

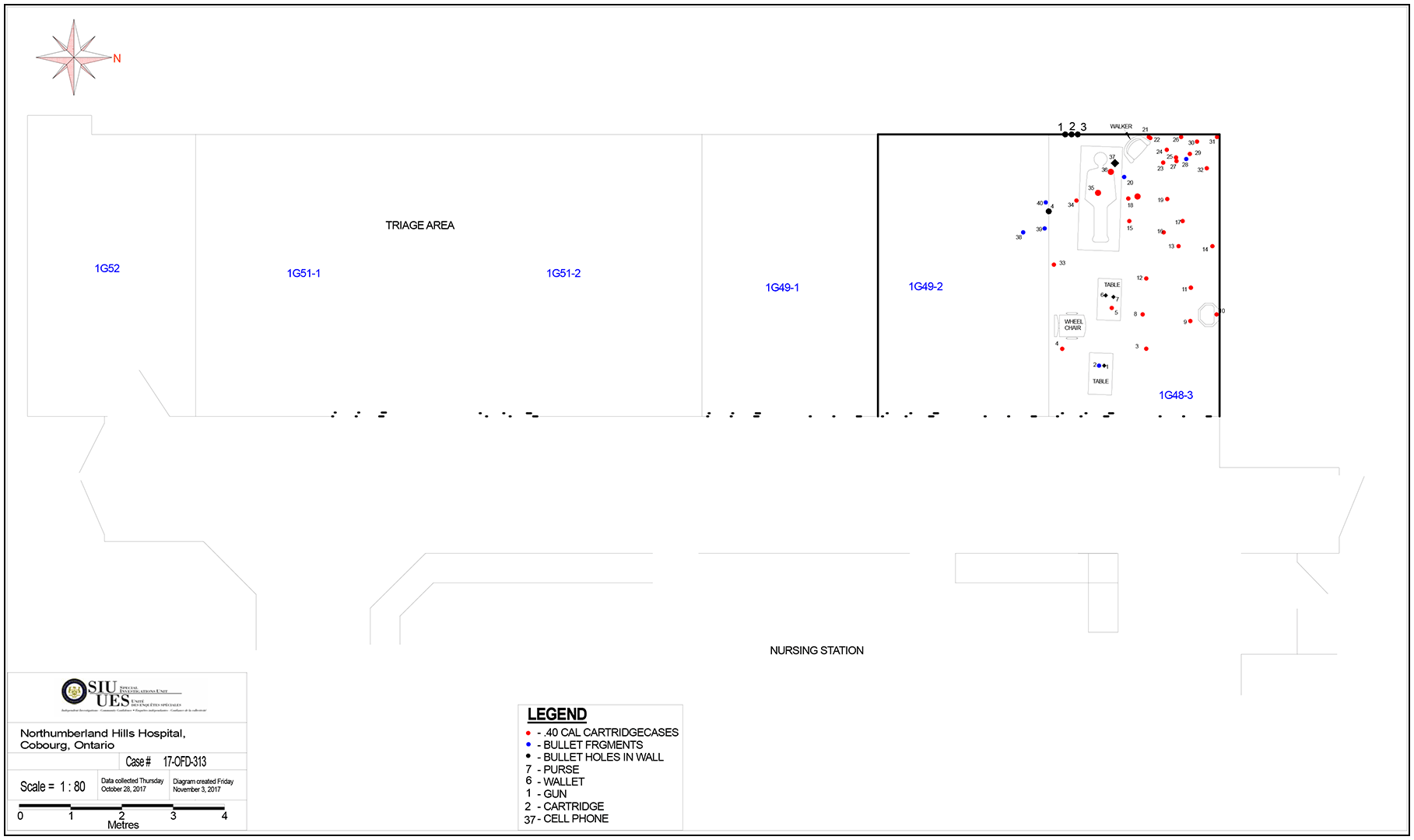

The scene was located in Triage Room #7 of the Northumberland Hills Hospital.

Scene Diagram

Physical Evidence

The Complainant's Firearm

Forensic Evidence

The following items were submitted to the Centre of Forensic Sciences (CFS) for analysis. The reports from the CFS indicated the following results:

Firearms Testing

Three firearms were seized by the SIU FIs at the scene: the two Glock pistols fired by the subject officers and a third pistol used by the Complainant to kill his wife.[1]

The following tests were conducted by CFS Scientists as outlined in their firearms report.

Particulars of the firearms as documented on the SIU property Status Review (PSR) are as follows:

Item 053

Glock 22 pistol issued to SO #2.

Item 065

Glock 22 pistol issued to SO #1.

Item 001

Taurus TCP handgun .380 calibre, semi-automatic pistol owned by the Complainant.

Police Firearms Examinations for Police Service Act Compliance

- The firearm issued to SO #2 met the criteria set forth in the Ontario Police Services Act "Technical Specifications for Handguns" excepting that twice, in repeated trigger pull testing, it was below the mandated threshold, and

- The firearm issued to SO #1 met the criteria set forth in the Ontario Police Services Act "Technical Specifications for Handguns" except that once, in repeated trigger pull testing, it was below the mandated threshold

Test to determine the distances from the muzzles of the police handguns to the target, the Complainant

Due to the intervening target surfaces of a bed sheet covering the Complainant and a double curtain at times in the path of the subject officers, distance determination testing was not conducted.

Test to match the cartridge cases to their respective firearms

Thirty cartridge cases ejected from Glock police handguns were submitted to the CFS to determine the number of rounds fired by each subject officer. The test resulted in the following rounds fired count for SO #2 and SO #1:

- SO #2 fired 16 rounds

- SO #1 fired 14 rounds, and

- The weapon used by the Complainant, a Taurus model PT738 semi-automatic pistol, had a six round magazine that fired .380 calibre rounds. One round was recovered from the head of WO #12 at autopsy. A further three rounds were in the magazine. One live round had been ejected by SO #1 after the fact, as a safety precaution, and one live round was chambered, thereby accounting for all six rounds

Projectile Recovery

- Twenty intact projectiles were recovered from the body of the Complainant

- Seven fragments of projectiles were recovered from the body of the Complainant

- Three projectiles were recovered from the west wall behind the Complainant's bed

- One projectile was recovered from the floor in the adjacent room south of the Complainant

- A single bullet fragment was recovered from under the gurney that held the Complainant

- One projectile was recovered from the clothing worn by the Complainant, and

- One projectile was found in the body bag used to carry the Complainant from the scene

Source DNA from the Taurus handgun

The DNA profile obtained from the firearm not belonging to either officer 'matched'[2] the DNA sourced from The Complainant at a probability of 1 in 180 trillion. The location and random match probability related to the sources from where the swabs were taken on the gun[3] prove that the Complainant loaded and handled the gun.

Expert Evidence

The post-mortem examination of the Complainant's body was conducted over two days, on October 30 and 31, 2017.

The final post-mortem report, which was received by the SIU on September 13, 2018, confirmed that the Complainant's cause of death was multiple gunshot wounds. The gunshot wounds were to the torso and extremities, including the index finger of his right hand and the ring and baby finger of his left hand. The gunshot wounds to the torso were fatal. The report concluded that:

The most medically significant gunshot wounds include those that injured the heart, lungs, liver, major blood vessels, and spine. The wounds were not survivable and death would be expected as a result of bleeding, failure of the heart to pump blood, loss of the ability to breathe, or a combination of these mechanisms. Death would be anticipated within seconds to minutes, presuming all of the wounds were sustained over a short period of time. Multiple copper jacketed projectiles (20), copper jackets (3), deformed grey metallic projectiles (3) and metallic fragments (3) were recovered during postmortem examination. Due to the number of wounds, in addition to the close proximity and overlapping nature of the wound tracks, in many instances it is not possible to definitively associate individual surface wounds to specific recovered projectiles or injuries to internal organs.

All of the gunshot wounds were associated with wound tracks that were front to back and left to right. The approximate distance between the muzzle of the guns and the surface of the body at the time of discharge could not be determined for any of the gunshot wounds. Nothing else caused, or contributed to, the Complainant's death.

On September 20, 2018, the forensic pathologist further clarified that none of the wounds sustained by the Complainant would be expected to have been immediately incapacitating and that the Complainant could still have been moving following any one of the wounds. The pathologist further explained that an injury to the heart or other organs in the torso would not necessarily immediately stop the brain and would not exclude the possibility of continued movement.

The toxicology report indicates a small amount of prescribed drugs were in the Complainant's system, none of which caused or contributed to his death.

Video/Audio/Photographic Evidence

The area of the hospital where the incident took place was not monitored or recorded on CCTV. No other video/audio or photographic evidence was located.

Communications Recordings

911 Call

At 12:51 a.m. on October 28, 2018, CW #6 called the 911 operator to report the shooting of CW #12. While she was supplying the operator with information, the police officers arrived and encountered the Complainant. Precisely two minutes and 27 seconds into the call, the first volley of police bullets was heard on the 911 tape. That volley lasted three seconds. A lull, which lasted 3.51 seconds ensued, during which time no shots were heard. A second volley of shots was heard which lasted a further three seconds. Elapsed time from the first sound of gunfire to the final shot was ten seconds.

The police transmissions communications recordings were obtained and reviewed.

Materials obtained from Police Service

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the CPS

- Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) Summary

- 911 Call Recordings

- Police Transmission Communications Recordings

- Notes of WO #1 and WO #2

- Police Firearms Acquired - CFP

- Private Firearm Acquired - CFP

- Directive: Use of Force

- CPS Procedure: Crime Call Public Disorder Analysis

- CPS Procedure: Offences Involving Firearms

- CPS Procedure: Sudden Death and Found Human Remains

- CPS Procedure: Homicide

- CPS Procedure: High Risk Offenders, and

- CPS policy specific to use of force by firearm

The SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from other sources:

- Cell phone forensic examination and analysis report from Ministry of Finance (MOF)

- CFS DNA Reports (x2)

- CFS Firearms Report (x2)

- CFS Toxicology Report for the Complainant

- Text messages from the Complainant's cell phone

- Ministry of Finance Reports on examination and analysis of the Complainant's cell phone

- Occurrence Report authored by hospital security, and

- Last Will and Testament and Power of Attorney for the Complainant and CW #12

Relevant legislation

Section 25(1), Criminal Code - Protection of persons acting under authority

25 (1) Every one who is required or authorized by law to do anything in the administration or enforcement of the law

- as a private person

- as a peace officer or public officer

- in aid of a peace officer or public officer, or

- by virtue of his office

is, if he acts on reasonable grounds, justified in doing what he is required or authorized to do and in using as much force as is necessary for that purpose.

25 (3) Subject to subsections (4) and (5), a person is not justified for the purposes of subsection (1) in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm unless the person believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the self-preservation of the person or the preservations of any one under that person's protection from death or grievous bodily harm.

Section 27, Criminal Code of Canada – Use of Force to Prevent Commission of Offence

27 Every one is justified in using as much force as is reasonably necessary

- to prevent the commission of an offence

- for which, if it were committed, the person who committed it might be arrested without warrant, and

- that would be likely to cause immediate and serious injury to the person or property of anyone; or

- To prevent anything being done that, on reasonable grounds, he believes would, if it were done, be an offence mentioned in paragraph (a)

Section 34, Criminal Code - Defence of Person – Use of Threat of Force

34 (1) A person is not guilty of an offence if

- They believe on reasonable grounds that force is being used against them or another person or that a threat of force is being made against them or another person

- The act that constitutes the offence is committed for the purpose of defending or protecting themselves or the other person from that use or threat of force, and

- The act committed is reasonable in the circumstances

(2) In determining whether the act committed is reasonable in the circumstances, the court shall consider the relevant circumstances of the person, the other parties and the act, including, but not limited to, the following factors:

- the nature of the force or threat

- the extent to which the use of force was imminent and whether there were other means available to respond to the potential use of force

- the person's role in the incident

- whether any party to the incident used or threatened to use a weapon

- the size, age, gender and physical capabilities of the parties to the incident

- the nature, duration and history of any relationship between the parties to the incident, including any prior use or threat of force and the nature of that force or threat;

- (f.1) any history of interaction or communication between the parties to the incident

- the nature and proportionality of the person's response to the use or threat of force, and

- whether the act committed was in response to a use or threat of force that the person knew was lawful

Section 88(1), Criminal Code - Possession of weapon for dangerous purpose

88 (1) Every person commits an offence who carries or possesses a weapon, an imitation of a weapon, a prohibited device or any ammunition or prohibited ammunition for a purpose dangerous to the public peace or for the purpose of committing an offence.

Section 95, Criminal Code – Possession of Prohibited or Restricted Firearm with Ammunition

95 (1) subject to subsection (3), every person commits an offence who, in any place, possesses a loaded prohibited firearm or restricted firearm, or an unloaded prohibited firearm or restricted firearm together with readily accessible ammunition that is capable of being discharged in the firearm, without being the holder of

- an authorization or a licence under which the person may possess the firearm in that place, and

- The registration certificate for the firearm

(2) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1)

- is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years, or

- is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding one year

Section 222, Criminal Code – Homicide

222 (1) A person commits homicide when, directly or indirectly, by any means, he causes the death of a human being.

- Homicide is culpable or not culpable

- Homicide that is not culpable is not an offence

- Culpable homicide is murder or manslaughter or infanticide

(5) A person commits culpable homicide when he causes the death or a human being,

- by means of an unlawful act

- by criminal negligence

- by causing that human being, by threats or fear of violence or by deception to do anything that causes his death, or

- by wilfully frightening that human being, in the case of a child or sick person

(6) Notwithstanding anything in this section, a person does not commit homicide within the meaning of this Act by reason only that he causes the death of a human being by procuring, by false evidence, the conviction and death of that human being by sentence of the law.

Section 229, Criminal Code – Murder, Manslaughter and Infanticide

229 Culpable homicide is murder

- Where the person who causes the death of a human being

- means to cause his death, or

- means to cause him bodily harm that he knows is likely to cause his death, and in reckless whether death ensues or not

- where a person, meaning to cause death to a human being or meaning to cause him bodily harm that he knows is likely to cause his death, and being reckless whether death ensures or not, by accident or mistake causes death to another human being, notwithstanding that he does not mean to cause death or bodily harm to that human being; or

- Where a person, for an unlawful object, does anything that he knows or ought to know is likely to cause death, and thereby causes death to a human being, notwithstanding that he desires to effect his object without causing death or bodily harm to any human being

Analysis and director’s decision

The Complainant and his wife, CW #12, were receiving support from a Personal Support Worker (PSW) as a result of age-related illnesses and decline. On October 27, 2017, the PSW for the Complainant and CW #12, CW #17, attended their home where she was met with a distressed CW #12 who was concerned that her husband was suicidal. As a result, CW #17 contacted her supervisor, and ultimately called 911 to have both the Complainant and CW #12 transported to hospital to be assessed.

Prior to leaving for the hospital, the Complainant returned to his room, where he was alone for a matter of minutes. He then met with paramedics and was placed on a stretcher for transport. In the presence of CW #17, the Complainant commented to his wife that "It's been a great 46 years of knowing you, I love you, but apparently 47 years wasn't in the cards for us." When reassured by CW #17 that they were just going to the hospital for a short while and that everything would be okay, the Complainant responded, "Well, somebody's got to cash in the chips eventually." The Complainant then expressed his thanks and appreciation to CW #17 for her care and support and told her good-bye. The Complainant later, at 9:27 p.m. (and for the last time), texted CW #17 from the hospital telling her that this was his final goodbye.

Once at hospital, the Complainant and CW #12 were placed in triage room seven in order to be seen and assessed by a doctor, once one became available; the lights in the room were off and the privacy curtain prevented anyone from looking into the room from the hallway.

At approximately 11:00 p.m., a loud bang was heard in the triage area, which was not immediately identifiable. As a result of investigating the possible source of the sound, CW #12 was located in the triage room with a gunshot wound to the right side of her head. The Complainant was observed to be in the adjacent bed, approximately two feet to CW #12's right side; he was covered by a blanket with his hands hidden from view. Upon being asked what had happened, the Complainant advised staff that his wife had shot herself; the Complainant was described as being very calm when he reported this to hospital staff. A 911 call was then made to report the incident, and two police officers from the Cobourg Police Service (CPS) arrived at the hospital shortly thereafter and while the 911 call was still in progress.

CW #12 was immediately removed from the triage room and taken to the resuscitation room in order to perform life-saving manoeuvres on her.[4] While in the resuscitation room, the blankets were pulled from CW #12 and a search for the gun was conducted, but it could not be located either in the possession of CW #12 or concealed on the stretcher. A nurse was heard to report, "She doesn't have the gun, the husband has the gun."

At that point, SO #1 and SO #2 arrived at the resuscitation room, where they were advised of the missing gun and the belief that the Complainant had shot his wife. Both police officers were observed by numerous witnesses to walk quickly toward the triage room where the Complainant was still located; neither officer was seen at that time to have un-holstered his firearm or to have anything in his hands. The police officers were described by various witnesses as being calm. The two police officers were accompanied by a nurse, CW #3.

Upon arrival at the Complainant's room, CW #3 heard one of the police officers ask the Complainant if he had a weapon, and then repeat the question a second time in what she described as a stern voice. The Complainant then acknowledged that he did, while pulling the blanket down from his chest area and lifting a firearm in his right hand.

Other witnesses from outside the room heard a man's voice repeatedly say words to the effect of "drop your weapon" or "drop your gun".

CW #3 observed the Complainant start to point the gun up with the muzzle pointed towards the officers, following which CW #3 heard gunshots, as many as ten, from the room, and she ran for her own safety.

CW #13, a hospital employee who observed the two police officers discharging their firearms into triage room seven, described one of the officers as looking scared, fearful, and doing something he did not want to do. CW #13 also saw the service pistol being repeatedly discharged in what he described as six to eight gunshots, one immediately after the other, with no pause in between, and the officer's finger moving faster than anything he had ever seen in his life.

A paramedic, CW #16, observed the two police officers approach the Complainant's room from her location in the resuscitation room and heard, approximately 30 to 45 seconds later, five or six quick gunshots, followed by a brief pause and then an additional four to six gunshots in succession.

When CW #16 later entered the triage room where the Complainant had been located, she observed a firearm resting on top of a small medical table in the room, about two to three feet from the Complainant's bed.

CW #5, a doctor, after resuscitation attempts on CW #12 were seen to be futile, declared her dead and then attended to triage room seven to see to the Complainant; he also pronounced the Complainant dead. He observed numerous shell casings on the floor of the room. CW #5 indicated that while he was in triage room seven, he heard one of the two police officers say that when they entered the room, they asked the Complainant where the gun was and that the Complainant had replied, "Right here," and started to draw it out; the officer demonstrated the movement as he spoke to CW #5 indicating that the Complainant had used his right hand to raise the handgun from his abdomen, on his left side.

Subsequent investigation revealed that SO #1 and SO #2 had discharged their firearms a total of 30 times, with SO #1 firing 14 times, while SO #2 had fired his handgun 16 times.

The bullet retrieved from CW #12's fatal head wound was matched to the firearm in the possession of the Complainant.[5] Examination of the Complainant's firearm further revealed three rounds still in the magazine, one live round in the chamber, and one round that had been ejected by SO #1 when he was making the firearm safe after the shooting, accounting for all six bullets that the firearm was capable of holding in its magazine.

A post-mortem examination on the body of the Complainant recovered 20 intact, and seven fragments of, projectiles in his body. The cause of death was noted in the post-mortem report as being multiple gunshot wounds to the torso. Nothing else contributed to his death.

SO #2, in his interview with SIU investigators, stated that he was partnered with SO #1 on October 27, 2017, and driving in the area of the Northumberland Hills Hospital (NHH) when they received a radio announcement about a woman who had reportedly shot herself in the head in the Emergency Department of the hospital; the officers arrived at the emergency entrance to the hospital within one minute of receiving the call.

SO #2 stated that as he and SO #1 entered the emergency area, he drew his firearm and held it down by his side in an inconspicuous manner. They were then directed to the resuscitation room where they were advised by CW #3 that, "Her (CW #12's) husband is in the last room at the end of the hall and we have not recovered a weapon." SO #2 indicated this was the first time he had heard that a husband was involved. Both police officers then quickly walked to triage room number seven.

Upon arriving at the triage room, SO #2 observed that the room was well lit, but the curtain was pulled across most of the window, restricting his view inside. SO #2 believed that the situation was one similar to that of an "Active shooter," for which he had received training, and he was concerned that if the Complainant was willing to shoot his wife, that he might have intentions to also shoot others who might enter the room.

SO #2 entered the room first and immediately pointed his firearm at the Complainant, who was lying on the bed. SO #2 clearly asked, "Where's the weapon, where's the weapon?" while observing that the Complainant had a blanket over his body, up to his mid-torso area.

SO #2 then observed the Complainant use his left hand to push the blanket down, while simultaneously raising a handgun in his right hand and pointing it directly at SO #2. SO #2, who described himself as now looking directly at the barrel of the firearm in the Complainant's outstretched hand, kept moving to his right as he fired his service weapon between eight to ten times, aiming at the Complainant's centre mass. SO #1 was also simultaneously firing his handgun at the Complainant.

SO #2 then described a brief lull in the firing wherein he noted that he could no longer see the Complainant's firearm, and SO #2 asked SO #1 if the threat was over. He then noted, however, that the Complainant was shaking or twitching under the blanket which, combined with his inability to see the firearm, caused both SO #2 and SO #1 to again fire their weapons at the Complainant.[6] SO #2 then completed an emergency reload of his firearm, dropping the empty magazine onto the floor. After the reload, however, SO #2 noted that the Complainant was no longer moving and he stood back and did not fire his weapon again, although he did not yet believe that the threat was completely over.

SO #2 then provided cover for SO #1, who donned latex gloves and approached the bed. SO #1 then pulled the blanket on the Complainant's body down and located the handgun at the left side of the Complainant. SO #1 racked the firearm once, ejecting the live round, and then placed the firearm and the ejected round on a side table near the foot of the bed. The dispatcher was then notified.

SO #2 advised that he was not in possession of a Conducted Energy Weapon (CEW) at the time of the incident, nor is he trained in the use of a CEW.

SO #2 further indicated that he was of the view that as he and SO #1 did not know the Complainant's intentions, and because they needed to prevent the Complainant from shooting the police, hospital staff, or patients/visitors, that a lethal use of force was the only appropriate option in the circumstances.

WO #2 stated that upon his arrival at the hospital, he immediately separated the two officers, whereupon SO #2 advised him that he and SO #1 had responded to a radio call at the hospital of a woman having shot herself in the Emergency Department. SO #2 had advised him that they then learned that hospital staff had been unable to locate the firearm and he and SO #1 were directed to the triage room where the Complainant was still located, and where the shooting had taken place. When SO #2 and SO #1 attended the Complainant's room, SO #2 shouted at the Complainant, "Where's the gun, where's the gun?" whereupon the Complainant raised his arms and pointed a firearm at them. Both officers then discharged their service pistols at the Complainant in response.

A review of the 911 recording reveals that while a nurse was still on the phone providing information to the 911 operator, the two police officers arrived at the hospital[7] and, precisely two minutes and 27 seconds into the call, the first volley of shots was heard on the tape, lasting three seconds, followed by a lull of 3.51 seconds, and then a second volley of shots lasting a further three seconds. From the initial gunshot by the police to the last, a period of ten seconds had elapsed.

Pursuant to s. 25(1) of the Criminal Code of Canada, a police officer, if he acts on reasonable grounds, is justified in using as much force as is necessary in the execution of a lawful duty. Further, pursuant to subsection 3:

(3) Subject to subsections (4) and (5), a person is not justified for the purposes of subsection (1) in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm unless the person believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the self-preservation of the person or the preservation of any one under that person's protection from death or grievous bodily harm.

As such, in order for SO #2 and SO #1 to qualify for protection from prosecution under section 25, it must be established that they were in the execution of a lawful duty, that they were acting on reasonable grounds, and that they used no more force than was necessary. Furthermore, pursuant to subsection 3, if death or grievous bodily harm is caused, it must be established that the police officers did so believing on reasonable grounds that it was necessary in order to preserve themselves or other persons from death or grievous bodily harm.

Turning first to the lawfulness of the Complainant's apprehension, it is clear from the 911 call and the statements of the civilian witnesses that there were reasonable grounds to believe that the Complainant was in possession of a firearm and had possibly just killed his wife. As such, there were reasonable grounds for the police to arrest the Complainant for the offences of possession of a weapon for a dangerous purpose contrary to s. 88 of the Criminal Code, possession of a restricted firearm with ammunition contrary to s. 95, and murder contrary to s. 229, in addition to numerous other offences relating to the possession of firearms when not properly licensed. As such, the apprehension and arrest of the Complainant was legally justified in the circumstances.

With respect to the other requirements pursuant to s.25(1) and (3), I am mindful of the state of the law as set out by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Nasogaluak [2010] 1 S.C.R. 206, as follows:

Police actions should not be judged against a standard of perfection. It must be remembered that the police engage in dangerous and demanding work and often have to react quickly to emergencies. Their actions should be judged in light of these exigent circumstances. As Anderson J.A. explained in R. v. Bottrell(1981), 60 C.C.C. (2d) 211 (B.C.C.A.):

In determining whether the amount of force used by the officer was necessary the jury must have regard to the circumstances as they existed at the time the force was used. They should have been directed that the appellant could not be expected to measure the force used with exactitude. [p. 218]

The court describes the test required under s.25 as follows:

Section 25(1) essentially provides that a police officer is justified in using force to effect a lawful arrest, provided that he or she acted on reasonable and probable grounds and used only as much force as was necessary in the circumstances. That is not the end of the matter. Section 25(3) also prohibits a police officer from using a greater degree of force, i.e. that which is intended or likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm, unless he or she believes that it is necessary to protect him- or herself, or another person under his or her protection, from death or grievous bodily harm. The officer's belief must be objectively reasonable. This means that the use of force under s. 25(3) is to be judged on a subjective-objective basis (Chartier v. Greaves, [2001] O.J. No. 634 (QL) (S.C.J.), at para. 59).

The decision of Justice Power of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in Chartier v. Greaves, [2001] O.J. No. 634, as adopted by the Supreme Court of Canada above, sets out other relevant provisions of the Criminal Code to be considered, as follows:

- Use of force to prevent commission of offence - Everyone is justified in using as much force as is reasonably necessary

- to prevent the commission of an offence

- for which, if it were committed, the person who committed it might be arrested without warrant, and

- that would be likely to cause immediate and serious injury to the person or property of anyone, or

- to prevent anything being done that, on reasonable grounds, he believes would, if it were done, be an offence mentioned in paragraph (a)

- to prevent the commission of an offence

This Section, therefore, authorizes the use of force to prevent the commission of certain offenses. Everyone" would include a police officer. The force must not be more than that which is reasonably necessary. Therefore, an objective test is called for. The Ontario Court of Appeal, in R. v. Scopelliti (1981), 63 C.C.C. (2d) 481 held that the use of deadly force can be justified only in either cases of self-defence or in preventing the commission of a crime likely to cause immediate and serious injury.

34(1) Self-defence against unprovoked assault - Everyone who is unlawfully assaulted without having provoked the assault is justified in repelling force by force if the force he uses is not intended to cause death or grievous bodily harm and is no more than is necessary to enable him to defend himself.

- Extent of justification - Everyone who is unlawfully assaulted and who causes death or grievous bodily harm in repelling the assault is justified if

- he causes it under reasonable apprehension of death or grievous bodily harm from the violence with which the assault was originally made or with which the assailant pursues his purposes, and

- he believes, on reasonable grounds, that he cannot otherwise preserve himself from death or grievous bodily harm

In order to rely on the defence under subsection (2) of Section 34, a police officer would have to demonstrate that he/she was unlawfully assaulted and caused death or grievous bodily harm to the assaulter in repelling the assault. The police officer must demonstrate that he or she reasonably apprehended that death or grievous bodily harm would result to him or her and that he or she, again on reasonable grounds, believed that he/she could not otherwise preserve himself/herself from death or grievous bodily harm. Again, the use of the term 'reasonable' requires the application of an objective test.

Further, the court sets out a number of other legal principles gleaned from the legal precedents cited, including the following:

- Whichever section of the Criminal Code is used to assess the actions of the police, the Court must consider the level of force that was necessary in light of the circumstances surrounding the event

- "Some allowance must be made for an officer in the exigencies of the moment misjudging the degree of force necessary to restrain a prisoner". The same applies to the use of force in making an arrest or preventing an escape. Like the driver of a vehicle facing a sudden emergency, the policeman "cannot be held to a standard of conduct which one sitting in the calmness of a court room later might determine was the best course." (Foster v. Pawsey) Put another way: It is one thing to have the time in a trial over several days to reconstruct and examine the events which took place on the evening of August 14th. It is another to be a policeman in the middle of an emergency charged with a duty to take action and with precious little time to minutely dissect the significance of the events, or to reflect calmly upon the decisions to be taken. (Berntt v. Vancouver)

- Police officers perform an essential function in sometimes difficult and frequently dangerous circumstances. The police must not be unduly hampered in the performance of that duty. They must frequently act hurriedly and react to sudden emergencies. Their actions must therefore be considered in the light of the circumstances

- "It is both unreasonable and unrealistic to impose an obligation on the police to employ only the least amount of force which might successfully achieve their objective. To do so would result in unnecessary danger to themselves and others. They are justified and exempt from liability in these situations if they use no more force than is necessary, having regard to their reasonably held assessment of the circumstances and dangers in which they find themselves" (Levesque v. Zanibbi et al.)

On the basis of the foregoing principles of law then, I must determine whether SO #2 and SO #1:

- Subjectively believed that they, or other persons, were at risk of death or grievous bodily harm from the Complainant, at the time that both police officers discharged their firearms, and

- Whether that belief was objectively reasonable, or, in other words, whether their actions would be considered reasonable by an objective bystander who had all of the information available to the officers at the time that they discharged their firearms

With respect to the first of these criteria, it is clear from the statement of SO #2 that he believed that he, or others, was at risk of death or grievous bodily harm at the time that he discharged his firearm. He based that belief on his observations at the time that the Complainant had in his possession a handgun that he pointed in the direction of the police officers, that numerous witnesses had already reported that there were reasonable grounds to believe that the Complainant had used that weapon to kill his wife, that the Complainant was aware of the police presence but had refused to comply with commands to drop his weapon, and that the Complainant, who was now pointing the gun in the officers' direction, had already proven that he was quite capable of discharging the firearm to take a life.

Furthermore, SO #2 stated that he considered that the incident was taking place in an area where there were numerous civilians and medical staff present and, as such, the Complainant not only posed a danger to the life of the two police officers, but to numerous other members of the public. As such, there is ample evidence to answer question 1 in the affirmative, that being that SO #2 did reasonably believe that he, and/or other persons, were at risk of death or grievous bodily harm from the Complainant at the time that SO #2 discharged his firearm.

While SO #1 did not provide a statement to SIU investigators, it is reasonable to infer, based on the evidence, that the concerns of SO #2 would have been shared by SO #1, who was in the exact same position as was SO #2, and had in his possession the same information.

Turning then to question 2, with respect to whether or not there were objectively reasonable grounds to believe that the lives of SO #1 and SO #2, or anyone under their protection, were at risk of death or grievous bodily harm from the Complainant, one need only refer to the observations of the one objective bystander who was with the police officers just prior to their discharging their firearms, that being CW #3, who actually witnessed the actions of the Complainant. CW #3 indicated that she heard one of the police officers ask the Complainant if he had a weapon on two occasions, before the Complainant responded in the affirmative and then pointed the gun upwards, following which she heard the first of the subsequent gunshots fired by the two officers. She also indicated that she had run from the room for her own safety.[8]

Furthermore, based on the evidence of another nurse, CW #23, as well as CW #1, CW #8, and CW #24, that either or both of SO #1 and SO #2 repeatedly shouted at the Complainant to drop his weapon, which he refused to do, it appears clear that the two subject officers did not immediately resort to the use of their firearms, but attempted to resolve the issue without a deadly use of force; the Complainant, however, refused to cooperate.

Having extensively reviewed all of the evidence, and the law relating to the justification in using force intended to cause death or grievous bodily harm when one believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for one's self-preservation from death or grievous bodily harm, or the death or bodily harm of others, I find in all of the circumstances that SO #2 and SO #1 believed that their lives, and those of hospital staff members and any civilians in the area, was in danger from the Complainant, which belief was objectively reasonable, and thus their actions in firing upon the Complainant were justified. I find that it would have been foolish and reckless for these two police officers to risk their own lives by waiting to see if a further shot was actually going to be fired from the weapon in the possession of the Complainant, which weapon was clearly a working firearm, had already reportedly been used to shoot and kill CW #12, and which the Complainant was now aiming at the officers. I find that that risk was not one that either of SO #1 or SO #2 should have had to take when faced with possibly being shot by a man who, by all appearances, was armed and was an imminent danger to both police officers, and to persons under their protection, and who clearly had the will and the ability to shoot and kill, as evidenced by the death of CW #12.

In concluding that SO #1 and SO #2 were justified in discharging their firearms at the Complainant, which ultimately caused his death, I will again refer to the judgment of the Supreme Court of Canada, as quoted above, as being particularly apt in this particular factual scenario, in that "It must be remembered that the police engage in dangerous and demanding work and often have to react quickly to emergencies. Their actions should be judged in light of these exigent circumstances."

I find, therefore, on this record, that the shots that were fired, more than 20 of which struck and subsequently killed the Complainant, were justified pursuant to s. 25(1) and (3) of the Criminal Code, and that SO #1 and SO #2, in preserving themselves or others from the infliction of grievous bodily harm or death by the Complainant, used no more force than was necessary to affect their lawful purpose. As such, I lack the reasonable grounds to believe that the actions exercised by SO #1 and SO #2 fell outside the limits prescribed by the

criminal law and instead find there are no grounds for proceeding with criminal charges in this case.

Date: September 26, 2018

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Endnotes

- 1) [1] The OPP’s parallel investigation into the death of CW #12 concluded that the Complainant shot his wife. [Back to text]

- 2) [2] At 15 STR loci. The random match probability was one in 180 trillion that a randomly selected individual unrelated to the person in question would coincidentally share the observed DNA profile. [Back to text]

- 3) [3] The upper left grip; right tip of the barrel; the grip backslide and button; and the side and textured portions of the magazine. The DNA came mostly from blood on the exterior sources from the gun and from epithelial cells on the magazine. [Back to text]

- 4) [4] This room had significantly greater amounts of medical equipment required for emergency care. [Back to text]

- 5) [5] The OPP’s parallel investigation into the death of CW #12 concluded that the Complainant shot his wife. [Back to text]

- 6) [6] In a phone call on September 20, 2018, in which the SIU requested clarification of the post-mortem report received on September 18, 2018, the forensic pathologist indicated that none of the wounds sustained by the Complainant would have been expected to be immediately incapacitating and that the Complainant could still have been moving after receiving any one of the wounds. The Pathologist further explained that an injury to the heart or other organs in the torso would not necessarily immediately stop the brain and would not exclude the possibility of continued movement. [Back to text]

- 7) [7] If SO #2’s estimate about the passage of time from when they were dispatched to their arrival at hospital is accurate, they would have been in the hospital between one and one and a half minutes before they discharged their firearms. [Back to text]

- 8) [8] She, however, was farther back than the officers and did not have the gun pointed directly at her, nor did she have the same duties imposed upon her as those imposed upon police officers. Thus, while it is not clear whether SO #1 believed that he had the gun pointed directly at him, he did not have the luxury of running away from the scene, while his partner’s life and the lives of other civilians were imminently at risk. [Back to text]

Note:

The signed English original report is authoritative, and any discrepancy between that report and the French and English online versions should be resolved in favour of the original English report.