SIU Director’s Report - Case # 17-TCI-349

Warning:

This page contains graphic content that can shock, offend and upset.

Contents:

Mandate of the SIU

The Special Investigations Unit is a civilian law enforcement agency that investigates incidents involving police officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The Unit’s jurisdiction covers more than 50 municipal, regional and provincial police services across Ontario.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Information restrictions

Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (“FIPPA”)

Pursuant to section 14 of FIPPA (i.e., law enforcement), certain information may not be included in this report. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:- Confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by law enforcement agencies; and

- Information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding.

- Subject Officer name(s);

- Witness Officer name(s);

- Civilian Witness name(s);

- Location information;

- Witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence; and

- Other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation.

Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 (“PHIPA”)

Pursuant to PHIPA, any information related to the personal health of identifiable individuals is not included. Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from this report because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner’s inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.Mandate engaged

The Unit’s investigative jurisdiction is limited to those incidents where there is a serious injury (including sexual assault allegations) or death in cases involving the police.

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the serious injury reportedly sustained by a 20-year-old man (the Complainant) during his arrest on November 26, 2017.

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the serious injury reportedly sustained by a 20-year-old man (the Complainant) during his arrest on November 26, 2017.

The Investigation

Notification of the SIU

At approximately 2:00 p.m. on November 26, 2017, the Toronto Police Service (TPS) reported a custody injury to the Complainant.The TPS reported that on that same date at 5:36 a.m., Emergency Task Force (ETF) officers executed a warrant at a residence in the City of Toronto during which three people were arrested, including the Complainant. The Complainant was then taken to the hospital where he was being treated for a collapsed lung.

The Team

Number of SIU Investigators assigned: 3 Number of SIU Forensic Investigators assigned: 1

Complainant:

20-year-old male interviewed, medical records obtained and reviewedCivilian Witnesses

CW #1 Interviewed CW #2 Interviewed

CW #3 Interviewed

Witness Officers

WO #1 Notes reviewed, interview deemed not necessaryWO #2 Notes reviewed, interview deemed not necessary

WO #3 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #4 Notes reviewed, interview deemed not necessary

WO #5 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #6 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #7 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #8 Notes reviewed, interview deemed not necessary

WO #9 Notes reviewed, interview deemed not necessary

WO #10 Notes reviewed, interview deemed not necessary

WO #11 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #12 Notes reviewed, interview deemed not necessary

Subject Officers

SO #1 Interviewed, but declined to submit notes, as is the subject officer’s legal right.SO #2 Declined interview and to provide notes, as is the subject officer’s legal right.

Incident Narrative

At 1:18 a.m. on November 26, 2017, a judicially authorized search warrant was granted to the TPS for the search of the residence of the Complainant. The search warrant authorized a search to attempt to locate firearms, ammunition, and related items.

At 6:38 a.m. on November 26, 2017, members of the TPS ETF made a dynamic entry at the residence named in the search warrant in order to execute the warrant and search for the enumerated items; the door was breached and a distractionary device (also known as a ‘flash bang’) was deployed. Upon entry, the police officers cleared first the main floor and then the second floor of the residence. On the second floor, a male was located hiding behind a bedroom door. When he was pulled out from behind the door, a firearm fell from his waistband onto the floor in the bedroom where the Complainant was located on the top bunk of a bunk bed.

When the Complainant was pulled from the top bunk by the SO, he landed on the floor near, and within reach, of the firearm. As the SO was dealing with the Complainant, who was not being cooperative, another officer observed the firearm and yelled “Gun! Gun!” Fearing that the Complainant might reach for the firearm, the SO delivered several knee and hand strikes to the Complainant in order to distract him, after which he was handcuffed and arrested, along with the two other occupants of the house.

Following his arrest, the Complainant was transported to hospital.

Nature of Injury/Treatment

The Complainant sustained a collapsed right lung, three fractures to the ribs on his right side and a non-displaced fracture of the nasal bone. The Complainant was discharged from the hospital later the same day and returned to the custody of the TPS.

On January 25, 2018, the Complainant confirmed that he had made a full recovery.

At 6:38 a.m. on November 26, 2017, members of the TPS ETF made a dynamic entry at the residence named in the search warrant in order to execute the warrant and search for the enumerated items; the door was breached and a distractionary device (also known as a ‘flash bang’) was deployed. Upon entry, the police officers cleared first the main floor and then the second floor of the residence. On the second floor, a male was located hiding behind a bedroom door. When he was pulled out from behind the door, a firearm fell from his waistband onto the floor in the bedroom where the Complainant was located on the top bunk of a bunk bed.

When the Complainant was pulled from the top bunk by the SO, he landed on the floor near, and within reach, of the firearm. As the SO was dealing with the Complainant, who was not being cooperative, another officer observed the firearm and yelled “Gun! Gun!” Fearing that the Complainant might reach for the firearm, the SO delivered several knee and hand strikes to the Complainant in order to distract him, after which he was handcuffed and arrested, along with the two other occupants of the house.

Following his arrest, the Complainant was transported to hospital.

Nature of Injury/Treatment

The Complainant sustained a collapsed right lung, three fractures to the ribs on his right side and a non-displaced fracture of the nasal bone. The Complainant was discharged from the hospital later the same day and returned to the custody of the TPS.

On January 25, 2018, the Complainant confirmed that he had made a full recovery.

Evidence

The Scene

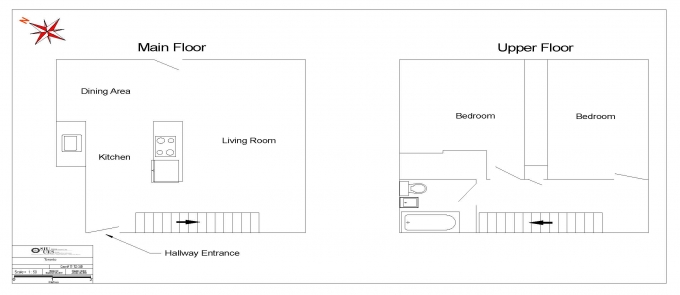

The residence searched was within a Toronto Community Housing (TCH) building in the City of Toronto. The unit searched was located on the ground floor. There were two entrances to the apartment, one through a common hallway and another through a back door. The back door lead to a patio and beyond the patio was a park and playground. The unit was a two story, two bedroom apartment. The apartment was very dirty and obviously in disarray before the search. The air in the apartment had the smell of marijuana and stale cigar smoke. There were no signs of violence other than one cupboard door which was partially off the hinges.Scene Diagram

Recovered Firearm:

The firearm recovered during the search was a Glock 10mm pistol which was black in colour and in good working condition. When recovered, the pistol had one live round in the chamber and eight live rounds in the magazine.

The serial number on the weapon was recorded and the weapon was retained by the TPS.

Forensic Evidence

No submissions were made to the Centre of Forensic Sciences.Video/Audio/Photographic Evidence

As the incident took place in a private residence, there were no audio/video recordings located.Communications Recordings

The police transmission communications recordings were obtained and reviewed.Materials obtained from Police Service

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the TPS:- Event Details Report (x2);

- Notes of WO #s 1-12;

- Search Warrant;

- Summary of Conversation;

- TPS Photos of Interior of Residence prior to Search;

- Police Transmissions Communications Recordings;

- TPS Full case-R v the Complainant et al; and

- TPS Photo of Seized Firearm.

The SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from other sources:

- Medical Records of the Complainant relating to this incident, obtained with his consent; and,

- Ambulance Call Report.

Relevant Legislation

Section 25(1), Criminal Code -- Protection of persons acting under authority

25 (1) Every one who is required or authorized by law to do anything in the administration or enforcement of the law

(a) as a private person,(b) as a peace officer or public officer,(c) in aid of a peace officer or public officer, or(d) by virtue of his office,

is, if he acts on reasonable grounds, justified in doing what he is required or authorized to do and in using as much force as is necessary for that purpose.

Section 91 (1), Criminal Code -- Unauthorized possession of firearm

91(1) Subject to subsection (4), every person commits an offence who possesses a prohibited firearm, a restricted firearm or a non-restricted without being the holder of

(a) a licence under which the person may possess it; and(b) in the case of a prohibited or a restricted firearm, a registration certificate for it.

(2) Subject to subsection (4), every person commits an offence who possesses a prohibited weapon, a restricted weapon, a prohibited device, other than a replica firearm, or any prohibited ammunition, without being the holder of a licence under which the person may possess it.

(3) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1) or (2)

(a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years; or(b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Section 95, Criminal Code – Possession of prohibited or restricted firearm with ammunition

95 (1) subject to subsection (3), every person commits an offence who, in any place, possesses a loaded prohibited firearm or restricted firearm, or an unloaded prohibited firearm or restricted firearm together with readily accessible ammunition that is capable of being discharged in the firearm, without being the holder of

(a) an authorization or a licence under which the person may possess the firearm in that place; and(b) The registration certificate for the firearm.

(2) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1)

(a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years, or(b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding one year.

Analysis and Director's Decision

On November 26, 2017, the Toronto Police Service (TPS) Guns and Gangs Task Force (GGTF) applied for, and obtained, a judicially authorized warrant to search a residence in a Toronto Housing Complex in the City of Toronto. The Complainant and his mother were known to reside at this residence. The information to obtain the search warrant was based on information obtained from a confidential informant that the residence was a ‘stash house’ used for firearms, and that it specifically held two long guns and two handguns at the time of the issuance of the warrant.

The search warrant was executed on November 26, 2017, at 6:38 a.m., with a dynamic no knock entry being performed by the Emergency Task Force (ETF), who initially entered and cleared the residence, to ensure the residence was safe for the officers from the GGTF to enter and search. During the clearing of the residence, three occupants were located in the house, that being CW #1, the Complainant, and CW #2. One loaded firearm, a Glock pistol, was also located by the ETF, with one round of ammunition in the chamber and eight rounds in the magazine.

During the course of the Complainant’s arrest, the subject officers, SO #1 and SO #2 of the ETF, used force and during his arrest, the Complainant was injured. A later assessment at hospital determined that the Complainant had sustained three fractured ribs on his right side, a related collapsed right lung, and a non-displaced nasal bone fracture. All three of the occupants allege that the officers resorted to an excessive use of force in arresting them. While only the Complainant sustained a serious injury, his arrest, and the force used to effect that arrest, triggered the mandate of the SIU and the investigation which followed.

During the course of the investigation, there were only three civilian witnesses to the incident who were interviewed, those being the three parties arrested inside the residence. Additionally, the notes of 12 police officers were reviewed, resulting in the interviews of five witness officers who had relevant evidence to offer; the first subject officer, SO #1, also consented to an interview, while the second subject officer, SO #2, did not; neither officer provided their memorandum book notes for review, as was their legal right.

There was unfortunately no surveillance video inside the residence, and the police transmissions recordings did not yield any evidence capable of either confirming or denying the allegations of an excessive use of force on the part of the arresting officers. The evidence of the three occupants of the house, who were arrested, and the arresting police officers, differs in a number of material aspects.

The facts that are not in dispute indicate that in the early morning hours of November 26, 2017, members of the ETF were tasked with executing a Criminal Code search warrant at CW #1’s residence in the City of Toronto, and the team of nine members, led by WO #6, attended a briefing conducted by WO #11 of the GGTF. During the briefing, the team was made aware that the GGTF had information that the residence contained firearms, possibly including two long guns and two handguns, that the residence was known to be used as a ‘stash house’ for firearms, and that gang members in the community were believed to use the residence for that purpose. Additionally, the team was provided the names of two individuals who might be found in the residence and information that each of those two individuals had extensive criminal records. The area where the residence was located was known for the presence of heavy gang activity. All of this information was provided and discussed at the briefing.

Following the briefing, a tactical meeting was held by WO #6, with his team, in which the potential issues and possible threats posed were discussed and a plan was laid out for the ETF entry into the residence, which was to be a dynamic entry because of the belief that the residence was a ‘stash house’ for firearms. The purpose of a dynamic entry is meant to prevent the residents being given prior notice of the intended entry by police and thereby preventing the residents possibly arming themselves as well as to allow police to take full advantage of the elements of surprise and distraction, in order to allow for a safer entry and containment of the occupants and to prevent a possible loss of life or the opportunity for an armed stand-off.

In order to fully take advantage of the elements of surprise and distraction, it was determined that immediately upon breaching the door, a distractionary device (also known as a ‘flash-bang’ or DD) was to be utilized, which would make a very loud and distracting sound and would expel smoke or emit a bright light immediately upon its deployment, thereby causing confusion and prevent any opportunity for the residents to dispose of evidence, escape, or mount a concerted response against police. Once the door was breached and the DD deployed, the members of the team were to locate and secure all parties and then turn over the residence to the GGTF investigators to execute the search warrant. The order of entry of the officers on the team was also established.

At 6:38 a.m., the ETF team was positioned at the front door of the residence and the breaching team breached the door. Upon entry, SO #1, who had been designated as number one, meaning he would be the first police officer through the door, loudly and repeatedly announced the presence of police and that they were in possession of a search warrant. The DD was then deployed, delivering a loud bang and a bright light, and SO #1 entered.

It is the responsibility of the first officer entering the residence to continue to make clear announcements and commands, which SO #1 then did. CW #1 was located on the main floor, sleeping on the couch, and SO #1 told her to get down on the floor; other team members then entered and took control of CW #1.

Three or four members of the team then made their way up the stairs, with another officer taking over making announcements about the police presence on the second floor.

Once on the second floor, SO #2 held a position covering the upper hallway, and WO #5 stopped behind SO #2 before moving to a closed bedroom door. WO #5 tried to open the door by kicking it, but the door only partially opened. WO #5 then forced his way inside the bedroom.

Upon forcing the door open, CW #2 was located crouched behind the door, hiding. While WO #5 was focused on CW #2, WO #6, who was directly behind WO #5, observed the Complainant lying on the top bunk of a bunk bed located against the far wall of the bedroom. WO #6 pointed his pistol at the Complainant and issued loud commands to the Complainant to show his hands; the Complainant was lying on his stomach and his hands were not visible. The Complainant did not respond to WO #6’s commands, but just lay there looking at him.

SO #1 then entered the room and directed his attention to the Complainant, allowing WO #5 and WO #6 to focus on CW #2. WO #5 and WO #6 then grabbed a hold of CW #2 and dragged him out from behind the door and out into the hallway, during which a black handgun fell to the bedroom floor, possibly having fallen from CW #2’s waistband. WO #6 immediately yelled, “Gun! Gun! Gun!” to warn his colleagues.

While WO #5 and WO #6 had been dealing with CW #2, SO #1 had entered the room and moved forward to deal with the Complainant. SO #1 was followed into the room by SO #2. From this point forward, the version of events as between SO #1 and the Complainant diverges greatly.

While both CW #1 and CW #2 allege that the police resorted to an excessive use of force in their individual arrests, neither was in a position to observe the arrest of the Complainant, as CW #1 was still on the first floor, where she had already been arrested, and CW #2 was in the process of being arrested in the hallway outside of the bedroom in which the Complainant was located.

According to the Complainant, he was sleeping in his bedroom when he was awoken by loud noises and observed CW #2 sleeping on a rocking chair in his room. The Complainant also advised that he noticed that there was a small pistol lying on the bed beside him and he assumed CW #2 had placed it there. The Complainant pushed the pistol off the bed with his arm, as he did not wish to have anything to do with any firearms.

The Complainant then observed three ETF officers enter the bedroom, yelling, “Put your hands up!” and other commands; the Complainant put his hands up. The Complainant described the three police officers as wearing black masks with only their eyes showing, their uniforms were green, and they were wearing bullet proof vests with “SWAT” written on them. Clearly, the ETF do not wear uniforms with the word “SWAT” on them, as they are not the “Special Weapons and Tactics” Unit, which is a unit of American police forces and of American television; nor do they wear green uniforms, with the ETF uniform being grey in colour with black vests and the uniforms bear the TPS logo on both the front and back panels. (A quick review on the internet does indeed confirm that some American SWAT teams wear green uniforms and have the word “SWAT” on the front and back of their vests).

The Complainant also described two detectives, and then a third, entering his room at the same time as the three ‘SWAT’ officers; he described these three detectives as being in plainclothes. This is directly contrary to the evidence of all of the police officers interviewed, both ETF and GGTF, all of whom firmly indicated that the ETF officers were all in their tactical uniforms and that the GGTF, who would not have been in ETF uniform, did not enter the residence until after all three occupants had been arrested and the residence was cleared and secured.

The Complainant indicated that the ‘SWAT’ officer, now known to have been SO #1 of the ETF, then grabbed onto the Complainant’s left arm and right shoulder and dragged him off the bed to the floor, where he landed on his shoulder and rolled onto his stomach. SO #1 pointed what looked to the Complainant like a pistol, at the Complainant’s head and told the Complainant to shut up and repeatedly told him to put his hands behind his back. Based on the evidence of SO #1, the weapon in his possession at the time was an MP5 long gun which required two hands to operate and was on a sling around his body.

The Complainant advised that he tried to put his hands behind his back, as directed, but that SO #1 stomped on him non-stop, with the first blow being to the Complainant’s side and the second to his head, causing his head to hit the floor.

The Complainant indicated that he saw the pistol that he had earlier pushed off of his bed lying on the floor nearby, but he did not reach for it. The Complainant then described SO #1 stomping on his head about five times, and at one point, kicking him in the groin. The Complainant could not say whether or not other officers also struck him. The Complainant indicated that he almost blacked out from the pain, but remained conscious and had difficulty breathing. He was then handcuffed with his hands behind his back by an unknown police officer and brought to his feet.

I note that other than the non-displaced fracture of the nasal bone, the Complainant did not sustain any facial injuries, which appears quite inconsistent with being stomped on his face five times by an ETF issued police boot, which one would have expected would have caused much greater damage to the Complainant’s face. I also note that in addition to the five stomps to his head, the Complainant only indicated one kick to his groin, where no injuries were noted, and one blow to his side.

The medical records indicate that the Complainant sustained three rib fractures to his right side and the opinion of the doctor was that his injuries were as consistent with a fall from a height (as in off of the bunk bed) as with a kick or a stomp. According to the triage records, the nurse noted the following:

The statement of SO #1 indicated that on November 26, 2017, he was wearing his grey marked tactical outfit with the TPS police logo on the front and back panels, heavy body armour, helmet and gloves, and he was equipped with full use of force equipment and was carrying an MP5 long gun which required two hands to operate and was on a sling around his body.

As SO #1 ascended the stairs to the second floor, behind three or four other team members, he heard a particular shout by another officer which indicated that contact had been made with someone inside the residence. Upon arriving at the top of the stairs, he observed WO #6 and WO #5 in a struggle with CW #2 in the doorway of the first bedroom. While SO #1 approached to assist, his attention was drawn inside the bedroom which was dimly lit and had not yet been cleared.

SO #1 observed the Complainant on the top bunk bed with only his face visible, and the remainder of his body under some bedding; the Complainant was watching the struggle to arrest CW #2. SO #1 described the Complainant’s reaction to the police presence as unusual in that while another team member was yelling at the Complainant to put his hands up, the Complainant failed to comply. SO #1 then identified himself as a police officer and again told the Complainant to show his hands with the Complainant still refusing to comply, which caused SO #1 concern. According to SO #1, had the Complainant shown his hands, the threat level would have been reduced, as that obviously would have confirmed whether or not the Complainant was armed.

SO #1 then entered the bedroom alone and continued with commands to the Complainant to show his hands. Finally the Complainant raised his head and said, “Why?” with what SO #1 described as defiance. SO #1 noted that the closet inside the bedroom had not yet been cleared, which, along with the Complainant’s refusal to show his hands, raised the threat level considerably in SO #1’s mind. That concern was further compounded by the fact that the Complainant was still on top of the upper bunk, which gave him an advantage over SO #1, who was standing below.

SO #1 advised that one of the disadvantages of carrying an MP5 long gun was that it required two hands to operate, making it difficult to engage with someone physically. SO #1 opined that normally he could have simply covered the Complainant with his firearm and waited for another officer to arrive for backup. In this case, however, where the closet had not yet been cleared and the Complainant was not showing his hands, SO #1 decided that he could not wait and needed to go ‘hands on’ with the Complainant.

SO #1 switched his firearm into safety mode and lowered it, holding it in one hand. He then stepped forward and used one hand to grab onto the Complainant, around the shoulder area, whereupon the Complainant immediately became actively resistant and pulled away. SO #1 continued to pull the Complainant toward him and off the bed. When the Complainant’s body was halfway to the floor, SO #1 pushed his body away from him, tucking the Complainant’s head and upper body underneath the top bunk, to avoid the Complainant striking his head on the floor. The Complainant then landed on the floor, with his shoulder and rib area making contact with the floor.

At that point, SO #2 arrived to assist. The Complainant was being actively resistant and SO #1 was unable to pin him to the floor. While SO #1 described the Complainant as not being assaultive, he was resisting any control that SO #1 attempted to exert over him. SO #2 then positioned himself on the Complainant’s lower half, when SO #1 heard WO #6 shout, “Gun! Gun!”

SO #1 assessed the situation at that point as escalating from one of active resistance, to one of a threat of serious bodily harm or death, and he immediately scanned the room and saw the black Glock handgun on the floor within arm’s length of the Complainant, who was facing toward the firearm.

At that point, considering all of the factors in play, SO #1 feared that he could be shot or forced to shoot the Complainant, if the Complainant was able to get his hands on the firearm. As a result, SO #1 delivered three knee strikes to the Complainant’s torso and rib area and punched the Complainant in the facial area a number of times in hopes of distracting him from reaching, and possibly using, the firearm. The manoeuvre worked, in that the Complainant reached up to cover his face with his hands, and SO #2 was able to handcuff one of the Complainant’s hands.

SO #1 indicated that he would not normally deliver a punch to someone, but in these particular circumstances he felt it was necessary as he felt the situation was escalating and he did not have any other viable option of dealing with the Complainant.

Once the Complainant had one hand handcuffed, he pulled his arm away and began to swing and flail his hands around with the handcuff attached. SO #1 continued to direct the Complainant to stop resisting and to give up his hands. On a scale of one to ten, SO #1 assessed the Complainant’s resistance as falling at a nine. After another 30 seconds, however, the Complainant was successfully handcuffed. He was then turned onto his side after complaining that he had trouble breathing and SO #1 observed a little blood on his facial area.

SO #1 estimated that the hands on interaction between himself and the Complainant lasted approximately two minutes.

Although SO #2 opted not to provide a statement, and WO #5 and WO #6 did not see the actual hands on interaction between SO #1 and SO #2 and the Complainant, the evidence of the other officers in the residence was consistent with respect to the outlying facts surrounding the arrest of the Complainant and corroborated the evidence of SO #1 to that degree.

I fully accept that just having been woken from sleep by a dynamic entry into his home by a team of ETF officers, the Complainant may have been confused as to exactly what occurred. Based on the injuries sustained, however, as well as the Complainant’s report to medical staff, as recorded in his medical records, that he was “punched in the face”, rather than stomped on his head, I do not accept his evidence that any police officer “stomped” on his head five times, as the obvious result of that type of assault, with an ETF issued police boot, would have resulted not only in the nondisplaced nasal bone fracture, which requires fairly little force, but in numerous fractures to many of the bones in the Complainant’s face, with his face being literally crushed by the force and velocity generated by such an extremely violent assault.

I also accept, however, that the Complainant was pulled, with force, from the top bunk and landed on the floor, striking his torso on the floor with some force, and that once down, he received several knee strikes to the rib area and a number of closed fisted strikes to the facial area, and that either the fall or the blow caused the rib fractures and related pneumothorax, and the facial blows caused the nondisplaced nasal bone fracture.

Having concluded, therefore, that the actions of SO #1 were the cause of the Complainant’s serious injuries, the only question remaining is whether or not those blows amounted to an excessive use of force in this particular factual situation.

Pursuant to s. 25(1) of the Criminal Code, a police officer, if he acts on reasonable grounds, is justified in using as much force as is necessary in the execution of a lawful duty. As such, in order for SO #1 and SO #2 to qualify for protection from prosecution pursuant to s. 25, it must be established that they were in the execution of a lawful duty, that they were acting on reasonable grounds, and that they used no more force than was necessary.

Turning first to the lawfulness of the Complainant’s apprehension, it is clear that the police lawfully entered the residence pursuant to a judicially authorized search warrant and were entitled to contain and detain the occupants while the warrant was being executed in order to prevent the disposal or destruction of evidence.

Furthermore, once a firearm was located within the bedroom over which the Complainant exercised control, the police officers had reasonable grounds to further arrest the Complainant for possession of an illegal firearm. As such, both the detention and the arrest of the Complainant were based on reasonable grounds and were pursuant to a lawful duty. The actions of SO #1 and SO #2 were therefore legally justified and exempt from prosecution, pursuant to s. 25 (1), as long as they used no more force than was necessary and justified to effect that lawful purpose.

In considering the amount of force used by the police officers in apprehending the Complainant, I have considered the direction from the Supreme Court of Canada as set out in R. v. Nasogaluak [2010] 1 S.C.R. 206, as follows:

Along the same lines, I have also considered the fulsome review of the case law in this regard, as set out by Justice Power of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in Chartier v. Greaves, [2001] O.J. No. 634, as follows:

Taking into consideration what was undoubtedly a very dynamic and fast-moving situation, I have also considered the decision of the Ontario Court of Appeal in R. v. Baxter (1975) 27 C.C.C. (2d) 96 (Ont. C.A.), that officers are not expected to measure the degree of their responsive force to a nicety.

Keeping the directions of our courts in mind, then, in considering whether or not an excessive use of force was resorted to in this instance, I have considered the following information that had been provided to the ETF prior to entering the residence on November 26, 2017, as follows:

Having considered all of this information, and the situation in which SO #1 found himself, with a potential that the Complainant, who was not complying with commands to show his hands and who resisted SO #1’s efforts to bring him down from the bunk bed, may be armed, I find that SO #1’s assessment of the situation as being a high threat level was quite reasonable in the circumstances and that he did not have the luxury, as he might otherwise have done, of simply covering the Complainant with his long gun and waiting for back up in the form of another team member, while the closet was not yet cleared, and the presence of other persons and/or firearms was a real possibility.

As such, firstly, I accept that SO #1 accurately assessed the situation and reacted appropriately when he put the safety on his long gun and entered the room to go “hands on” with the Complainant. The alternative, of course, of resorting to the use of his long gun, could obviously have had far greater and more lethal consequences for the Complainant.

Furthermore, when the Complainant refused to comply with commands to show his hands, and then pulled away from SO #1, SO #1 was fully justified in pulling the Complainant from the bunk bed and down onto the floor. While the Complainant may have been injured when he struck the floor, I accept that SO #1 did whatever possible to prevent the Complainant being injured by his descent, and that SO #1’s intent when removing the Complainant from the bunk was not to injury him, but simply to contain him and ensure the safety of himself and his fellow officers.

Finally, when the warning “Gun! Gun! Gun!” was voiced out by WO #6, and SO #1 observed the firearm within the Complainant’s reach, I can accept, without any reluctance, that the urgency of the situation would have greatly escalated with the risk of loss of life to SO #1 and his colleagues, if not to the other people in the house, if the Complainant was not immediately incapacitated and handcuffed. As such, despite the serious injuries to the Complainant, in this factual situation, with such risk and potentially fatal consequences, I cannot find the actions of SO #1 to amount to an excessive use of force on these facts. As quoted by Justice Power in Chartier v. Grieves, above,

In conclusion, I find that the actions resorted to by SO #1, and by SO #2, were neither excessive on this particular fact situation, nor do they fall outside of the limits of the criminal law. SO #1 was faced with a situation of extreme urgency, one which he had been trained to deal with, and he dealt with that situation and eliminated the risk that the Complainant continued to pose until he was restrained and the firearm removed from within his reach. I further note that once the Complainant was handcuffed, no further force was resorted to, nor was there any allegation of any further use of force by the Complainant or anyone else.

On this record, I find that the evidence is not sufficient to satisfy me that there are reasonable grounds to believe that any police officer resorted to an excessive use of force in restraining and arresting the Complainant. In sum, there is no basis for the laying of criminal charges and none shall issue.

Date: October 29, 2018

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

The search warrant was executed on November 26, 2017, at 6:38 a.m., with a dynamic no knock entry being performed by the Emergency Task Force (ETF), who initially entered and cleared the residence, to ensure the residence was safe for the officers from the GGTF to enter and search. During the clearing of the residence, three occupants were located in the house, that being CW #1, the Complainant, and CW #2. One loaded firearm, a Glock pistol, was also located by the ETF, with one round of ammunition in the chamber and eight rounds in the magazine.

During the course of the Complainant’s arrest, the subject officers, SO #1 and SO #2 of the ETF, used force and during his arrest, the Complainant was injured. A later assessment at hospital determined that the Complainant had sustained three fractured ribs on his right side, a related collapsed right lung, and a non-displaced nasal bone fracture. All three of the occupants allege that the officers resorted to an excessive use of force in arresting them. While only the Complainant sustained a serious injury, his arrest, and the force used to effect that arrest, triggered the mandate of the SIU and the investigation which followed.

During the course of the investigation, there were only three civilian witnesses to the incident who were interviewed, those being the three parties arrested inside the residence. Additionally, the notes of 12 police officers were reviewed, resulting in the interviews of five witness officers who had relevant evidence to offer; the first subject officer, SO #1, also consented to an interview, while the second subject officer, SO #2, did not; neither officer provided their memorandum book notes for review, as was their legal right.

There was unfortunately no surveillance video inside the residence, and the police transmissions recordings did not yield any evidence capable of either confirming or denying the allegations of an excessive use of force on the part of the arresting officers. The evidence of the three occupants of the house, who were arrested, and the arresting police officers, differs in a number of material aspects.

The facts that are not in dispute indicate that in the early morning hours of November 26, 2017, members of the ETF were tasked with executing a Criminal Code search warrant at CW #1’s residence in the City of Toronto, and the team of nine members, led by WO #6, attended a briefing conducted by WO #11 of the GGTF. During the briefing, the team was made aware that the GGTF had information that the residence contained firearms, possibly including two long guns and two handguns, that the residence was known to be used as a ‘stash house’ for firearms, and that gang members in the community were believed to use the residence for that purpose. Additionally, the team was provided the names of two individuals who might be found in the residence and information that each of those two individuals had extensive criminal records. The area where the residence was located was known for the presence of heavy gang activity. All of this information was provided and discussed at the briefing.

Following the briefing, a tactical meeting was held by WO #6, with his team, in which the potential issues and possible threats posed were discussed and a plan was laid out for the ETF entry into the residence, which was to be a dynamic entry because of the belief that the residence was a ‘stash house’ for firearms. The purpose of a dynamic entry is meant to prevent the residents being given prior notice of the intended entry by police and thereby preventing the residents possibly arming themselves as well as to allow police to take full advantage of the elements of surprise and distraction, in order to allow for a safer entry and containment of the occupants and to prevent a possible loss of life or the opportunity for an armed stand-off.

In order to fully take advantage of the elements of surprise and distraction, it was determined that immediately upon breaching the door, a distractionary device (also known as a ‘flash-bang’ or DD) was to be utilized, which would make a very loud and distracting sound and would expel smoke or emit a bright light immediately upon its deployment, thereby causing confusion and prevent any opportunity for the residents to dispose of evidence, escape, or mount a concerted response against police. Once the door was breached and the DD deployed, the members of the team were to locate and secure all parties and then turn over the residence to the GGTF investigators to execute the search warrant. The order of entry of the officers on the team was also established.

At 6:38 a.m., the ETF team was positioned at the front door of the residence and the breaching team breached the door. Upon entry, SO #1, who had been designated as number one, meaning he would be the first police officer through the door, loudly and repeatedly announced the presence of police and that they were in possession of a search warrant. The DD was then deployed, delivering a loud bang and a bright light, and SO #1 entered.

It is the responsibility of the first officer entering the residence to continue to make clear announcements and commands, which SO #1 then did. CW #1 was located on the main floor, sleeping on the couch, and SO #1 told her to get down on the floor; other team members then entered and took control of CW #1.

Three or four members of the team then made their way up the stairs, with another officer taking over making announcements about the police presence on the second floor.

Once on the second floor, SO #2 held a position covering the upper hallway, and WO #5 stopped behind SO #2 before moving to a closed bedroom door. WO #5 tried to open the door by kicking it, but the door only partially opened. WO #5 then forced his way inside the bedroom.

Upon forcing the door open, CW #2 was located crouched behind the door, hiding. While WO #5 was focused on CW #2, WO #6, who was directly behind WO #5, observed the Complainant lying on the top bunk of a bunk bed located against the far wall of the bedroom. WO #6 pointed his pistol at the Complainant and issued loud commands to the Complainant to show his hands; the Complainant was lying on his stomach and his hands were not visible. The Complainant did not respond to WO #6’s commands, but just lay there looking at him.

SO #1 then entered the room and directed his attention to the Complainant, allowing WO #5 and WO #6 to focus on CW #2. WO #5 and WO #6 then grabbed a hold of CW #2 and dragged him out from behind the door and out into the hallway, during which a black handgun fell to the bedroom floor, possibly having fallen from CW #2’s waistband. WO #6 immediately yelled, “Gun! Gun! Gun!” to warn his colleagues.

While WO #5 and WO #6 had been dealing with CW #2, SO #1 had entered the room and moved forward to deal with the Complainant. SO #1 was followed into the room by SO #2. From this point forward, the version of events as between SO #1 and the Complainant diverges greatly.

While both CW #1 and CW #2 allege that the police resorted to an excessive use of force in their individual arrests, neither was in a position to observe the arrest of the Complainant, as CW #1 was still on the first floor, where she had already been arrested, and CW #2 was in the process of being arrested in the hallway outside of the bedroom in which the Complainant was located.

According to the Complainant, he was sleeping in his bedroom when he was awoken by loud noises and observed CW #2 sleeping on a rocking chair in his room. The Complainant also advised that he noticed that there was a small pistol lying on the bed beside him and he assumed CW #2 had placed it there. The Complainant pushed the pistol off the bed with his arm, as he did not wish to have anything to do with any firearms.

The Complainant then observed three ETF officers enter the bedroom, yelling, “Put your hands up!” and other commands; the Complainant put his hands up. The Complainant described the three police officers as wearing black masks with only their eyes showing, their uniforms were green, and they were wearing bullet proof vests with “SWAT” written on them. Clearly, the ETF do not wear uniforms with the word “SWAT” on them, as they are not the “Special Weapons and Tactics” Unit, which is a unit of American police forces and of American television; nor do they wear green uniforms, with the ETF uniform being grey in colour with black vests and the uniforms bear the TPS logo on both the front and back panels. (A quick review on the internet does indeed confirm that some American SWAT teams wear green uniforms and have the word “SWAT” on the front and back of their vests).

The Complainant also described two detectives, and then a third, entering his room at the same time as the three ‘SWAT’ officers; he described these three detectives as being in plainclothes. This is directly contrary to the evidence of all of the police officers interviewed, both ETF and GGTF, all of whom firmly indicated that the ETF officers were all in their tactical uniforms and that the GGTF, who would not have been in ETF uniform, did not enter the residence until after all three occupants had been arrested and the residence was cleared and secured.

The Complainant indicated that the ‘SWAT’ officer, now known to have been SO #1 of the ETF, then grabbed onto the Complainant’s left arm and right shoulder and dragged him off the bed to the floor, where he landed on his shoulder and rolled onto his stomach. SO #1 pointed what looked to the Complainant like a pistol, at the Complainant’s head and told the Complainant to shut up and repeatedly told him to put his hands behind his back. Based on the evidence of SO #1, the weapon in his possession at the time was an MP5 long gun which required two hands to operate and was on a sling around his body.

The Complainant advised that he tried to put his hands behind his back, as directed, but that SO #1 stomped on him non-stop, with the first blow being to the Complainant’s side and the second to his head, causing his head to hit the floor.

The Complainant indicated that he saw the pistol that he had earlier pushed off of his bed lying on the floor nearby, but he did not reach for it. The Complainant then described SO #1 stomping on his head about five times, and at one point, kicking him in the groin. The Complainant could not say whether or not other officers also struck him. The Complainant indicated that he almost blacked out from the pain, but remained conscious and had difficulty breathing. He was then handcuffed with his hands behind his back by an unknown police officer and brought to his feet.

I note that other than the non-displaced fracture of the nasal bone, the Complainant did not sustain any facial injuries, which appears quite inconsistent with being stomped on his face five times by an ETF issued police boot, which one would have expected would have caused much greater damage to the Complainant’s face. I also note that in addition to the five stomps to his head, the Complainant only indicated one kick to his groin, where no injuries were noted, and one blow to his side.

The medical records indicate that the Complainant sustained three rib fractures to his right side and the opinion of the doctor was that his injuries were as consistent with a fall from a height (as in off of the bunk bed) as with a kick or a stomp. According to the triage records, the nurse noted the following:

… per pt (patient) was asleep at home, house got raided and was beat up. Pt c/o (complains of) R ribs pain. Bleeding from mouth as well and punched in face. …

The statement of SO #1 indicated that on November 26, 2017, he was wearing his grey marked tactical outfit with the TPS police logo on the front and back panels, heavy body armour, helmet and gloves, and he was equipped with full use of force equipment and was carrying an MP5 long gun which required two hands to operate and was on a sling around his body.

As SO #1 ascended the stairs to the second floor, behind three or four other team members, he heard a particular shout by another officer which indicated that contact had been made with someone inside the residence. Upon arriving at the top of the stairs, he observed WO #6 and WO #5 in a struggle with CW #2 in the doorway of the first bedroom. While SO #1 approached to assist, his attention was drawn inside the bedroom which was dimly lit and had not yet been cleared.

SO #1 observed the Complainant on the top bunk bed with only his face visible, and the remainder of his body under some bedding; the Complainant was watching the struggle to arrest CW #2. SO #1 described the Complainant’s reaction to the police presence as unusual in that while another team member was yelling at the Complainant to put his hands up, the Complainant failed to comply. SO #1 then identified himself as a police officer and again told the Complainant to show his hands with the Complainant still refusing to comply, which caused SO #1 concern. According to SO #1, had the Complainant shown his hands, the threat level would have been reduced, as that obviously would have confirmed whether or not the Complainant was armed.

SO #1 then entered the bedroom alone and continued with commands to the Complainant to show his hands. Finally the Complainant raised his head and said, “Why?” with what SO #1 described as defiance. SO #1 noted that the closet inside the bedroom had not yet been cleared, which, along with the Complainant’s refusal to show his hands, raised the threat level considerably in SO #1’s mind. That concern was further compounded by the fact that the Complainant was still on top of the upper bunk, which gave him an advantage over SO #1, who was standing below.

SO #1 advised that one of the disadvantages of carrying an MP5 long gun was that it required two hands to operate, making it difficult to engage with someone physically. SO #1 opined that normally he could have simply covered the Complainant with his firearm and waited for another officer to arrive for backup. In this case, however, where the closet had not yet been cleared and the Complainant was not showing his hands, SO #1 decided that he could not wait and needed to go ‘hands on’ with the Complainant.

SO #1 switched his firearm into safety mode and lowered it, holding it in one hand. He then stepped forward and used one hand to grab onto the Complainant, around the shoulder area, whereupon the Complainant immediately became actively resistant and pulled away. SO #1 continued to pull the Complainant toward him and off the bed. When the Complainant’s body was halfway to the floor, SO #1 pushed his body away from him, tucking the Complainant’s head and upper body underneath the top bunk, to avoid the Complainant striking his head on the floor. The Complainant then landed on the floor, with his shoulder and rib area making contact with the floor.

At that point, SO #2 arrived to assist. The Complainant was being actively resistant and SO #1 was unable to pin him to the floor. While SO #1 described the Complainant as not being assaultive, he was resisting any control that SO #1 attempted to exert over him. SO #2 then positioned himself on the Complainant’s lower half, when SO #1 heard WO #6 shout, “Gun! Gun!”

SO #1 assessed the situation at that point as escalating from one of active resistance, to one of a threat of serious bodily harm or death, and he immediately scanned the room and saw the black Glock handgun on the floor within arm’s length of the Complainant, who was facing toward the firearm.

At that point, considering all of the factors in play, SO #1 feared that he could be shot or forced to shoot the Complainant, if the Complainant was able to get his hands on the firearm. As a result, SO #1 delivered three knee strikes to the Complainant’s torso and rib area and punched the Complainant in the facial area a number of times in hopes of distracting him from reaching, and possibly using, the firearm. The manoeuvre worked, in that the Complainant reached up to cover his face with his hands, and SO #2 was able to handcuff one of the Complainant’s hands.

SO #1 indicated that he would not normally deliver a punch to someone, but in these particular circumstances he felt it was necessary as he felt the situation was escalating and he did not have any other viable option of dealing with the Complainant.

Once the Complainant had one hand handcuffed, he pulled his arm away and began to swing and flail his hands around with the handcuff attached. SO #1 continued to direct the Complainant to stop resisting and to give up his hands. On a scale of one to ten, SO #1 assessed the Complainant’s resistance as falling at a nine. After another 30 seconds, however, the Complainant was successfully handcuffed. He was then turned onto his side after complaining that he had trouble breathing and SO #1 observed a little blood on his facial area.

SO #1 estimated that the hands on interaction between himself and the Complainant lasted approximately two minutes.

Although SO #2 opted not to provide a statement, and WO #5 and WO #6 did not see the actual hands on interaction between SO #1 and SO #2 and the Complainant, the evidence of the other officers in the residence was consistent with respect to the outlying facts surrounding the arrest of the Complainant and corroborated the evidence of SO #1 to that degree.

I fully accept that just having been woken from sleep by a dynamic entry into his home by a team of ETF officers, the Complainant may have been confused as to exactly what occurred. Based on the injuries sustained, however, as well as the Complainant’s report to medical staff, as recorded in his medical records, that he was “punched in the face”, rather than stomped on his head, I do not accept his evidence that any police officer “stomped” on his head five times, as the obvious result of that type of assault, with an ETF issued police boot, would have resulted not only in the nondisplaced nasal bone fracture, which requires fairly little force, but in numerous fractures to many of the bones in the Complainant’s face, with his face being literally crushed by the force and velocity generated by such an extremely violent assault.

I also accept, however, that the Complainant was pulled, with force, from the top bunk and landed on the floor, striking his torso on the floor with some force, and that once down, he received several knee strikes to the rib area and a number of closed fisted strikes to the facial area, and that either the fall or the blow caused the rib fractures and related pneumothorax, and the facial blows caused the nondisplaced nasal bone fracture.

Having concluded, therefore, that the actions of SO #1 were the cause of the Complainant’s serious injuries, the only question remaining is whether or not those blows amounted to an excessive use of force in this particular factual situation.

Pursuant to s. 25(1) of the Criminal Code, a police officer, if he acts on reasonable grounds, is justified in using as much force as is necessary in the execution of a lawful duty. As such, in order for SO #1 and SO #2 to qualify for protection from prosecution pursuant to s. 25, it must be established that they were in the execution of a lawful duty, that they were acting on reasonable grounds, and that they used no more force than was necessary.

Turning first to the lawfulness of the Complainant’s apprehension, it is clear that the police lawfully entered the residence pursuant to a judicially authorized search warrant and were entitled to contain and detain the occupants while the warrant was being executed in order to prevent the disposal or destruction of evidence.

Furthermore, once a firearm was located within the bedroom over which the Complainant exercised control, the police officers had reasonable grounds to further arrest the Complainant for possession of an illegal firearm. As such, both the detention and the arrest of the Complainant were based on reasonable grounds and were pursuant to a lawful duty. The actions of SO #1 and SO #2 were therefore legally justified and exempt from prosecution, pursuant to s. 25 (1), as long as they used no more force than was necessary and justified to effect that lawful purpose.

In considering the amount of force used by the police officers in apprehending the Complainant, I have considered the direction from the Supreme Court of Canada as set out in R. v. Nasogaluak [2010] 1 S.C.R. 206, as follows:

Police actions should not be judged against a standard of perfection. It must be remembered that the police engage in dangerous and demanding work and often have to react quickly to emergencies. Their actions should be judged in light of these exigent circumstances. As Anderson J.A. explained in R. v. Bottrell (1981), 60 C.C.C. (2d) 211 (B.C.C.A.):

In determining whether the amount of force used by the officer was necessary the jury must have regard to the circumstances as they existed at the time the force was used. They should have been directed that the appellant could not be expected to measure the force used with exactitude. [p. 218]

Along the same lines, I have also considered the fulsome review of the case law in this regard, as set out by Justice Power of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in Chartier v. Greaves, [2001] O.J. No. 634, as follows:

(h) Whichever section of the Criminal Code is used to assess the actions of the police, the Court must consider the level of force that was necessary in light of the circumstances surrounding the event.(i) "Some allowance must be made for an officer in the exigencies of the moment misjudging the degree of force necessary to restrain a prisoner". The same applies to the use of force in making an arrest or preventing an escape. Like the driver of a vehicle facing a sudden emergency, the policeman "cannot be held to a standard of conduct which one sitting in the calmness of a court room later might determine was the best course." (Foster v. Pawsey) Put another way: It is one thing to have the time in a trial over several days to reconstruct and examine the events which took place on the evening of August 14th. It is another to be a policeman in the middle of an emergency charged with a duty to take action and with precious little time to minutely dissect the significance of the events, or to reflect calmly upon the decisions to be taken. (Berntt v. Vancouver).(j) Police officers perform an essential function in sometimes difficult and frequently dangerous circumstances. The police must not be unduly hampered in the performance of that duty. They must frequently act hurriedly and react to sudden emergencies. Their actions must therefore be considered in the light of the circumstances.(k) "It is both unreasonable and unrealistic to impose an obligation on the police to employ only the least amount of force which might successfully achieve their objective. To do so would result in unnecessary danger to themselves and others. They are justified and exempt from liability in these situations if they use no more force than is necessary, having regard to their reasonably held assessment of the circumstances and dangers in which they find themselves" (Levesque v. Zanibbi et al.).

Taking into consideration what was undoubtedly a very dynamic and fast-moving situation, I have also considered the decision of the Ontario Court of Appeal in R. v. Baxter (1975) 27 C.C.C. (2d) 96 (Ont. C.A.), that officers are not expected to measure the degree of their responsive force to a nicety.

Keeping the directions of our courts in mind, then, in considering whether or not an excessive use of force was resorted to in this instance, I have considered the following information that had been provided to the ETF prior to entering the residence on November 26, 2017, as follows:

- This residence was believed to be a ‘stash house’ for firearms, based on information provided by a confidential informant;

- That same informant had apparently provided information that two long guns and two handguns were in the residence;

- The residence was believed to be used by gang members;

- At least two known offenders, with lengthy criminal records, were associated with this residence and were believed to possibly be inside the residence when the entry was made;

- The residence was in an area known for a significant gang presence and heavy gang activity;

- The Complainant was refusing to cooperate with directions to show his hands;

- The Complainant’s hands were hidden from view under the bedding in a house known to contain firearms;

- A firearm was seen within reach of the Complainant, after he had been removed from the top bunk;

- Another male (who was one of the individuals with a lengthy criminal record that the police were aware of), who had been hiding behind the door in the Complainant’s bedroom, had already been observed to have a firearm in his waistband, which then fell to the floor;

- The bedroom was dimly lit, the closet had not yet been cleared, and other police officers were engaged with CW #2, or elsewhere in the residence, leaving SO #1 alone to deal with the Complainant; and

- On all of the information provided to the ETF in their briefing, this situation was one described as presenting as a high threat level for the potential for death or serious bodily harm.

Having considered all of this information, and the situation in which SO #1 found himself, with a potential that the Complainant, who was not complying with commands to show his hands and who resisted SO #1’s efforts to bring him down from the bunk bed, may be armed, I find that SO #1’s assessment of the situation as being a high threat level was quite reasonable in the circumstances and that he did not have the luxury, as he might otherwise have done, of simply covering the Complainant with his long gun and waiting for back up in the form of another team member, while the closet was not yet cleared, and the presence of other persons and/or firearms was a real possibility.

As such, firstly, I accept that SO #1 accurately assessed the situation and reacted appropriately when he put the safety on his long gun and entered the room to go “hands on” with the Complainant. The alternative, of course, of resorting to the use of his long gun, could obviously have had far greater and more lethal consequences for the Complainant.

Furthermore, when the Complainant refused to comply with commands to show his hands, and then pulled away from SO #1, SO #1 was fully justified in pulling the Complainant from the bunk bed and down onto the floor. While the Complainant may have been injured when he struck the floor, I accept that SO #1 did whatever possible to prevent the Complainant being injured by his descent, and that SO #1’s intent when removing the Complainant from the bunk was not to injury him, but simply to contain him and ensure the safety of himself and his fellow officers.

Finally, when the warning “Gun! Gun! Gun!” was voiced out by WO #6, and SO #1 observed the firearm within the Complainant’s reach, I can accept, without any reluctance, that the urgency of the situation would have greatly escalated with the risk of loss of life to SO #1 and his colleagues, if not to the other people in the house, if the Complainant was not immediately incapacitated and handcuffed. As such, despite the serious injuries to the Complainant, in this factual situation, with such risk and potentially fatal consequences, I cannot find the actions of SO #1 to amount to an excessive use of force on these facts. As quoted by Justice Power in Chartier v. Grieves, above,

“Some allowance must be made for an officer in the exigencies of the moment misjudging the degree of force necessary to restrain a prisoner … It is one thing to have the time in a trial over several days to reconstruct and examine the events which took place on the evening of August 14th. It is another to be a policeman in the middle of an emergency charged with a duty to take action and with precious little time to minutely dissect the significance of the events, or to reflect calmly upon the decisions to be taken.”

In conclusion, I find that the actions resorted to by SO #1, and by SO #2, were neither excessive on this particular fact situation, nor do they fall outside of the limits of the criminal law. SO #1 was faced with a situation of extreme urgency, one which he had been trained to deal with, and he dealt with that situation and eliminated the risk that the Complainant continued to pose until he was restrained and the firearm removed from within his reach. I further note that once the Complainant was handcuffed, no further force was resorted to, nor was there any allegation of any further use of force by the Complainant or anyone else.

On this record, I find that the evidence is not sufficient to satisfy me that there are reasonable grounds to believe that any police officer resorted to an excessive use of force in restraining and arresting the Complainant. In sum, there is no basis for the laying of criminal charges and none shall issue.

Date: October 29, 2018

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Note:

The signed English original report is authoritative, and any discrepancy between that report and the French and English online versions should be resolved in favour of the original English report.